Block-printing ushered in the great epoch. The first block-books were produced somewhere in Holland.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

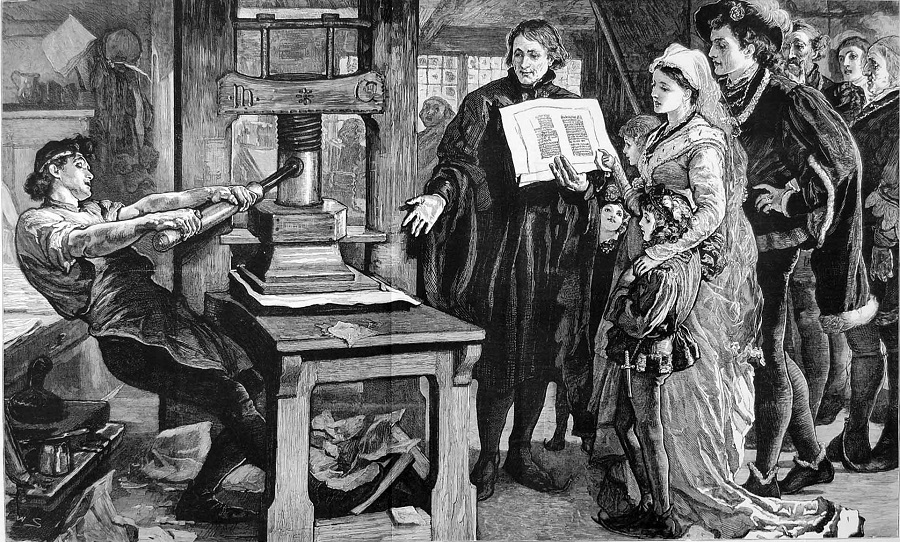

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But before I proceed to modern times, I am bound to note that the Chinese, who seem to have been many centuries in advance of Europe in most of the industrial arts, are supposed to have practiced block-printing, just as they do now, more than a thousand years ago. Nor does the complicated nature of their written language, which consists of more than one hundred thousand word-signs, admit of any readier mode. But they print, or rather rub off, impressions with such speed — seven hundred sheets per hour — that, until the introduction of steam, they far outstripped Europeans. Gibbon, it will be remembered, regrets that the emperor Justinian, who lived in the sixth century, did not introduce the art of printing from the Chinese, instead of their silk manufacture.

Block-printing ushered in the great epoch; and the first dawn of it in Europe seems to have been single prints of saints and scriptural subjects, with a line or two of description engraved on the same wooden plate. These are for the most part lost; but there is one in existence, large and exceedingly fine, of St. Christopher, with two lines of inscription, dated 1423, believed to have been printed with the ordinary printing-press. It was found in the library of a monastery near Augsburg, and is therefore presumed to be of German execution. Till lately this was the earliest-dated evidence of block-printing known; but there has since been discovered at Malines, and deposited at Brussels, a wood-cut of similar character, but assumed to be Dutch or Flemish, dated “MCCCCXVIII”; and though there seems no reason to doubt the genuineness of the cut, it is asserted that the date bears evidence of having been tampered with.

There is a vague tradition, depending entirely on the assertion of a writer named Papillon, not a very reliable authority, which would give the invention of wood-cut-printing to Venice, and at a very early period. He asserts that he once saw a set of eight prints, depicting the deeds of Alexander the Great, each described in verse, which were engraved in relief, and printed by a brother and sister named Cunio, at Ravenna, in 1285. But though the assertion is accredited by Mr. Ottley, it is generally disbelieved.

There is reason to suppose that playing-cards, from wooden blocks, were produced at Venice long before the block-books, even as early as 1250; but there is no positive evidence that they were printed; and some insist that they were produced either by friction or stencil-plates. It seems, however, by no means unlikely that cards, which were in most extensive use in the Middle Ages, should, for the sake of cheapness, have been printed quite as early, if not earlier, than even figures of saints; and the same artists are presumed to have produced both.

From single prints, with letter-press inscriptions, the next stage, that of a series of prints accompanied by letter-press, was obvious. Such are our first recognized block-books, among which are the Apocalypse, and the Biblia Pauperum (or Poor Man’s Bible), supposed to have been printed at Haarlem by Laurence Koster, between 1420 and 1430; I say supposed, because we have no positive evidence either of the person, place, or date; and Erasmus, who was born at Rotterdam in 1467, and always ready to advance the honor of his country, is silent on the subject. We rely chiefly upon the testimony of Ulric Zell, an eminent printer of Cologne, who is quoted in the Cologne Chronicle of 1499, and Hadrian Junius, a Dutch historian of repute, who wrote in the next century. Both agree in ascribing the invention of book-printing from wooden blocks, as well as the first germ of movable wood and metallic type printing, to Haarlem; and Junius adds the name of Laurence Koster. His surname of Koster is derived from his office, which was that of custodian, sexton, or warden of the Cathedral Church of Haarlem. The story told of the accident by which the discovery was made is as follows:

Koster, as he was one day walking in a wood adjoining the city, about the year 1420, cut some letters on the bark of a beech tree, from which he took impressions on paper for the amusement of his brother-in-law’s children. The idea then struck him of enlarging their application; and, being a man of an ingenious turn, he invented a thicker and more tenacious ink than was in common use, which blotted, and began to print figures from wooden tablets or blocks, to which he added several lines of letters, first solid, and then separate or movable. These wooden types are said to have been fastened together with string.

One thing seems pretty clear, which is, that, whether or not Koster was the printer, the first block-books were produced somewhere in Holland, as several are in Dutch, a language seldom, if ever, printed out of its own country. They were generally printed in light-brown ink, like a sepia drawing, which, I think, was adopted with a view to their being colored — a condition in which we find the greater part of them. When these prints were colored they presented very much the appearance of the Low Country stained-glass windows.

Block-books continued to be printed and reprinted, first in Holland and afterward in Germany, with considerable activity, for twenty or thirty years, during which period we had several editions of the Biblia Pauperum, the Ars Moriendi (or Art of Dying), the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, and many others, chiefly devoted to the promulgation of scripture history. The earliest ones are printed, or rather transferred by friction — and therefore on one side only of the paper — entirely from solid blocks; later on, some portions were printed with movable types of wood; and at last the letter-press was entirely of movable metal types. Junius says that Koster by degrees exchanged his wooden types for leaden ones, and these for pewter; and I will add that it is not unlikely they may have been cast in lead or pewter plates from the wooden blocks, as metal-casting was well understood at the time.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.