The magnitude of the task he has accomplished can only be appreciated by measuring it against the centuries of heroic effort that lay behind.

Continuing The Search for the North Pole,

our selection from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Search for the North Pole.

Time: 1909

Place: North Pole

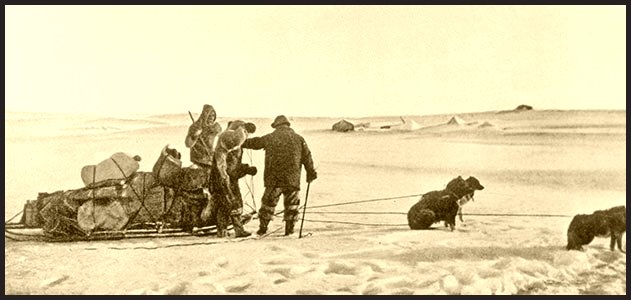

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Another notable European expedition was that equipped and headed by the Duke of Abruzzi, the well-known member of the Italian royal family. Abruzzi was also aiming at the Pole, but, varying Nansen’s method, he selected Franz Josef Land as his base and planned to advance from there by sledges. His ship, the Polar Star, set out in 1899 and wintered at Franz Josef Land, where Abruzzi himself had the misfortune to be injured. He was thus compelled to entrust the sledge expedition of the following spring to his assistant, Captain Cagni. The method adopted for this was that which Peary has made famous. Several supporting parties went out with Cagni, so that when the last of these fell back, he went onward with a full supply of provisions and a full team of dogs. Managed in this way, and aided by good fortune and smoother ice than previous explorers had met, the sledge journey was far longer than any of the earlier ones across this difficult semi-sea. The advance party travelled three hundred miles, and reached a point even farther north than Nansen had attained from the Fram. Cagni’s mark, 86°33′, remained the “farthest north” until Peary exceeded it six years later, and then, trying once more, reached the Pole itself. Cagni turned back because failing provisions compelled him to do so, and he only barely regained his ship, living for the last fortnight on his starving dogs.

Even before the Abruzzi expedition a new expedient had been tried in this prolonged struggle for the Pole. Such had been the progress in aeronautics that a daring balloonist, Salomon Andree, suggested the possibility of drifting across the Arctic Ocean, perchance even over the Pole itself, in a balloon. Andree was a Swedish government engineer, and his dangerous project was, after much discussion, officially aided by his country. A Swedish warship carried Andree and two companions to Spitzbergen, where their balloon was made ready. Then, in July, 1897, seizing an opportunity when the wind blew northward, the three adventurers soared away into the unknown. From Spitzbergen to the Pole was over six hundred miles in a direct line, and beyond the Pole they must float as far again or probably much farther before they could hope to reach any habitable shore. A message was dropped from the balloon on the third day of its ascent, telling of baffling winds and a slow drift northeastward. Nothing definite has ever since been heard or seen of these heroic adventurers. That they perished, no one can longer doubt. Their names are added to the tragic list of victims of the lure of the North. But how or where or when they met their frozen fate we can only guess. Occasional rumors come from the American Eskimos, of a great bird dropping from the sky, of dead men borne by the bird to their coast; but such rumors are usually the mere echo of the white man’s questions. Perhaps the balloon and its grim freight lie yet upon the Arctic drift ice, floating back and forth through that vast wilderness. More probably they have been engulfed and will be hid forever in the ocean’s deeps. Yet man has not been stayed from venturing; another aeronaut, Walter Wellman, has planned, and though repeatedly baffled still plans, to succeed where Andree perished.

Such, in brief, is the story of the North, leaving out of account the remarkable work of Commander Peary, the hero who at length has reached the goal for which so many strove. The magnitude of the task he has accomplished can only be appreciated by measuring it against the centuries of heroic effort that lay behind, the thousands of men who have taxed endurance and ingenuity to their utmost limit, the hundreds who have been driven beyond that limit, and perished. Yet all had failed.

Peary owes his success, as he himself has told us in recent speeches, to his patience and experience. The effort and courage of former explorers could not be exceeded; their personal knowledge of the North and familiarity with its conditions could. Peary for a score of years devoted all his life and all his study to acquiring that knowledge through repeated Arctic trips, repeated efforts toward one goal after another. He plucked victory, as many another workman has done, from the suffering and disappointment of repeated defeat.

Robert Edwin Peary is an American, born in Pennsylvania in 1856. He was educated at Bowdoin College and entered the United States Navy as a civil engineer in 1881. In this capacity he worked for some years on the United States Government survey for the Nicaragua ship canal, and in 1887-8 was at the head of the survey. He rose to the rank of commander in the navy before withdrawing from active service. His first northern trip was one of observation along the coast of Greenland in 1886, at just about the time that Nansen was engaged in the same work. Peary scaled the vast continental ice cap of Greenland and penetrated for some distance toward the interior. The Arctic ambition seized him for its own.

Returning to Greenland in 1891, as head of an expedition sent out by the Philadelphia Academy, Peary spent his first winter in the North. The next spring, starting from a base near Smith Sound, he accomplished a remarkable sledge journey of twelve hundred miles forth and back across northern Greenland. He reached its northeast coast at a spot which he named Independence Bay, thus establishing the fact that Greenland is indeed an island, not, as some had thought, a continent extending perhaps to the Pole and beyond. Next to his last and greatest feat, this was perhaps Peary’s most notable achievement in the North. It brought him medals and honors both at home and abroad. Moreover, it fixed his intention to devote himself permanently to the cause of Arctic discovery.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.