The Chinese appear to have the best title to be considered the inventors of both cotton and linen paper.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

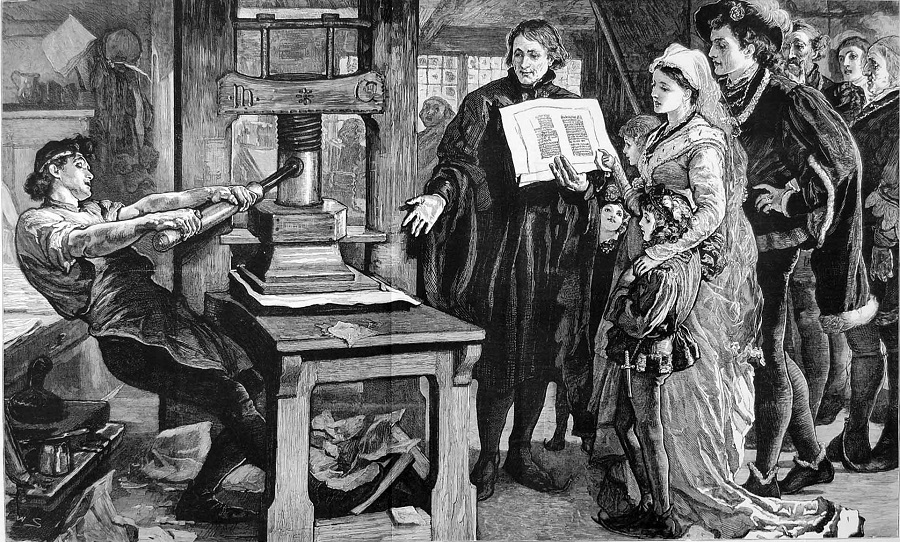

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Parchment and vellum — which are made from the skin of animals, the former from sheep or goat, the latter from calf, both prepared with lime — were in use at a very early period, long before their accredited introduction. It has been by some supposed that Eumenes, King of Pergamus, who lived about B.C. 190, was the inventor of parchment; but it was known much earlier, as may be seen by several references to it in the Bible (Isaiah, viii. i; Jeremiah, xxxvi. 2; Ezekiel, xi. 9). It is, however, very probable that it may have been brought to perfection at Pergamus, as it was one of the principal articles of commerce of that kingdom.

Parchment, in early times, was not only expensive, but often very difficult to procure; whence arose the practice of erasing old writing from it, and engrossing it a second time. Such manuscripts are called “palimpsests.” Modern art has found the means of discharging the more recent ink, and thus restoring the original writing, by which means we have recovered many valuable pieces, particularly Cicero’s lost book, de Republica and some fragments of his Orations.

The most ancient manuscripts, both on papyrus and parchment, were kept in rolls, called in Latin volumina, whence our English word “volume.” Chinese paper, made from the bark of the bamboo, the mulberry, or the khu-ku tree, and so extremely thin that it can only be used on one side, is supposed to have been invented fifty years before the Christian era or earlier. Chinese rice-paper is made from the stems of the bread-fruit tree, cut into slices and pressed. The skins of all kinds of animals are used — among them the African skin, of a brown color, upon which the Hebrew Pentateuch and service-books used in the Jewish synagogues were formerly written. Silk-paper was prepared for the most part in Spain and its colonies, but was never brought to much perfection. Asbestos, a fibrous mineral, was made into paper, tolerably light and pliant, which, being incombustible, was denominated “eternal paper.” Herodotus tells us that cloth was made of asbestos by the Egyptians; and Pliny mentions napkins made of it in A.D. 74. We know by tradition that the intestines of a serpent served for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey; and that the Koran was written in part on shoulder-bones of mutton, kept in a domestic chest by one of Mahomet’s wives.

We now come to the great period of writing-papers made from cotton and linen rags, as used at the present day, and which from the first were so perfect that they have since undergone no material improvement. Cotton-paper was an Eastern invention, probably introduced in the ninth century, although not generally used in Europe till about the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Greek manuscripts are found upon it of the earlier period, and Italian manuscripts of the later. It seems to have prevailed at particular periods, in particular countries, according to the facilities for procuring it, as it now does almost exclusively in America. Linen paper, the most valuable and important of all the bases available for writing or printing, is likewise supposed to have been introduced into Europe from the East, early in the thirteenth century, although not in general use till the fourteenth.

Before the end of the fourteenth century, paper-mills had been established in many parts of Europe, first in Spain, and then successively in Italy, Germany, Holland, and France. They seem to have come late into England, for Caxton printed all his books on paper imported from the Low Countries; and it was not till Winkin de Worde succeeded him, in 1495, that paper was manufactured in England. The Chinese are supposed to have used it for centuries before, and appear to have the best title to be considered the inventors of both cotton and linen paper.

Paper may be made of many other materials, such as hay, straw, nettles, flax, grasses, parsnips, turnips, colewort leaves, wood-shavings, indeed of anything fibrous; but as the invention of printing is not concerned in them, I see no occasion to consider their merits.

Before I pass from paper, it may not be irrelevant to say a word or two on the names by which we distinguish the sorts and sizes. The term “post-paper” is derived from the ancient water-mark, which was a post-horn, and not from its suitableness to transport by post, as many suppose. The original watermark of a fool’s cap gave the name to that paper, which it still retains, although the fool’s cap was afterward changed to a cap of liberty, and has since undergone other changes. The smaller size, called “pot-paper,” took its name from having at first been marked with a flagon or pot. Demy-paper, on which octavo books are usually printed, is so called from being originally a “demi” or half-sized paper; the term is now, however, equally applied to hard or writing papers. Hand-cap, which is a coarse paper used for packing, bore the water-mark of an open hand.

I will now say a few words about pens and ink, for without them we could neither have had printing nor books. Pens are of great antiquity, and are frequently alluded to in the Bible. Pens of iron, which may mean styles, are mentioned by Job and Jeremiah. Reed pens are known to have been in common use by the ancients, and some were discovered at Pompeii. Pens of gold and silver are alluded to by the classical writers, and there is evidence of the use of quills in the seventh century. Of whatever material the pen was made, it was called a calamus, whence our familiar saying, “currente calamo” (“with a flowing pen”). The use of styles, or iron pens, must have been very prevalent in ancient days, as Suetonius tells us that the emperor Caligula incited the people to massacre a Roman senator with their styles; and, previous to that, Caesar had wounded Cassius with his style.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.