A different phase of Arctic exploration began in 1670 with the formation of the Hudson Bay fur company.

Continuing The Search for the North Pole,

our selection from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Search for the North Pole.

Place: Northern Lands

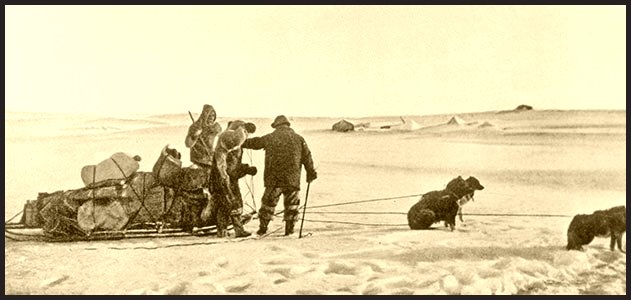

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The two centuries following Hudson produced little definite result. The great bay which he had discovered was explored. Baffin, another Englishman, in 1616 sailed north through Davis Strait and circumnavigated that huge sea or bay which bears his name on the west of Greenland. Looking into the northern outlet of his bay, by which Peary was to achieve the Pole, Baffin named it Smith Sound. There he found his northward progress blocked by ice, so sailing down the west coast of Baffin’s Bay, the explorer saw and named Lancaster Sound, which was, as future generations were to learn, the true opening of the Northwest passage. Unfortunately, Baffin’s discoveries did not become widely known and were somewhat discredited.

A different phase of Arctic exploration began in 1670 with the formation of the Hudson Bay fur company. Its employees, in the search for Canadian furs, roamed the north of the American continent, gradually learning its extent and mapping out its coast. The course of the great Mackenzie River was followed to its mouth in the Arctic Ocean by Alexander Mackenzie in 1789. Lieutenant, afterward Sir John, Franklin traveled over nearly a thousand miles of the icy shore west of the Mackenzie. Other explorers filled in the gaps of knowledge, until Rae completed the task in 1847, and the last bit of coastline was mapped out.

The Asiatic coastline was also established, being traced step after step by Russian explorers. Before 1640 most of the great Siberian rivers had been discovered and followed to their mouths by Cossack chieftains, demanding tribute for the Russian government. As early as 1648 a Siberian Cossack, Deshneff, made a boat journey from the Kolyma River around the northeastern extremity of Russia, and traded for furs with the natives on the Pacific coast. He must thus have passed without knowing it through Behring Strait, the passage, scarce sixty miles wide, which separates Asia from America.

These early Russian discoveries were made, as were those in America, in the way of business. But in 1725 the Czar, Peter the Great, resolved that Siberia should be regularly explored. He entrusted the work to Vitus Behring, a Dane. Under Behring elaborate preparations were made and considerable work done in charting the northern Pacific and the sea which bears his name. In his last voyage Behring landed on the American coast, discovered and named the huge peak of Mount St. Elias, and saw many of the Alaskan islands. He was finally wrecked upon Behring Island in Behring Sea. Compelled to winter there, the explorers suffered agonies. Many of them, including their captain, died (1741). The survivors built a ship from the wreck of theirs and in the following year sailed back to Siberia.

Other Russian explorers, sent out by Peter the Great or his successors, mapped the north Siberian coast, travelling some times by ship, sometimes by sledge. In 1743 a sledging party under Lieutenant Chelyuskin rounded the cape which has been named after him, the highest point of the Asiatic mainland, in fact the most northerly continental point of the world, 77° 4i’.

Meanwhile, Englishmen were not idle. In addition to their continental explorations in America, at least three naval expeditions were dispatched to the North by the government during the eighteenth century. These, however, accomplished little, unless we except the work of that under the celebrated explorer Cook. Cook in 1778 sailed northward from the Pacific through Behring Strait, and examined the Arctic coast of both Asia and America for some hundred miles. He also endeavored to sail directly north, but was blocked in his advance by the ice. Thus, at the beginning of the nineteenth century little more of the North was known than in Hudson’s day. The outlines of the Asiatic and American continents had been partly and roughly mapped out; but no man had yet penetrated nearer to the Pole than had Hudson in 1607. Possibly, of course, some of the whaling-ships cruising where Hudson had cruised off Spitzbergen had been slightly farther north than he; but none could have much exceeded him and none had given official notice of the fact. His 8o° 23′ remained the record of “farthest north.”

We come now to what may fairly be termed the modern period of Polar exploration. In 1817 Captain Scoresby, the ablest and most scientific of the English whaling captains, brought back word to England that a change had taken place, that the northern seas had never before been so free from ice. The captain urged that exploration, both in the interest of the whalers and of science, be vigorously recommenced. The government promptly announced a reward of £20,000 to any ship which made the Northwest passage, and one of £5,000 to any explorer who reached within one degree of the Pole. The comparative rewards may be taken as measuring what England thought the relative importance of the two goals. The government did more than this, it sent out naval expeditions; and from 1818 to 1857 there was scarce a year during which English warships were not ploughing the northern seas. Chiefly, these efforts were confined to the region west of Green land, in the search for the Northwest passage. Parry penetrated Lancaster Sound and reached far to the westward in 1819. Ross discovered the magnetic pole on the American mainland in 1831. In the Spitzbergen region, Parry in 1827 made a resolute effort to reach the Pole itself. This expedition of Parry’s was the first of the many which have since abandoned ships and attempted to cross the great northern ice pack with sledges. Parry and his men dragged their sledges by hand, and penetrated as far north as 82o 45′. They found the advance over the broken and often watery ice to be terribly laborious. Sometimes they could struggle onward only four miles a day. At length heavy winds from the north began to sweep the ice floes southward faster than the men could travel over the rugged surface. Thus, the expedition was driven back. Its northward mark stood as the record for half a century more.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.