We now come to the great epoch of printing: the first invention, of movable metal or fusile types.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

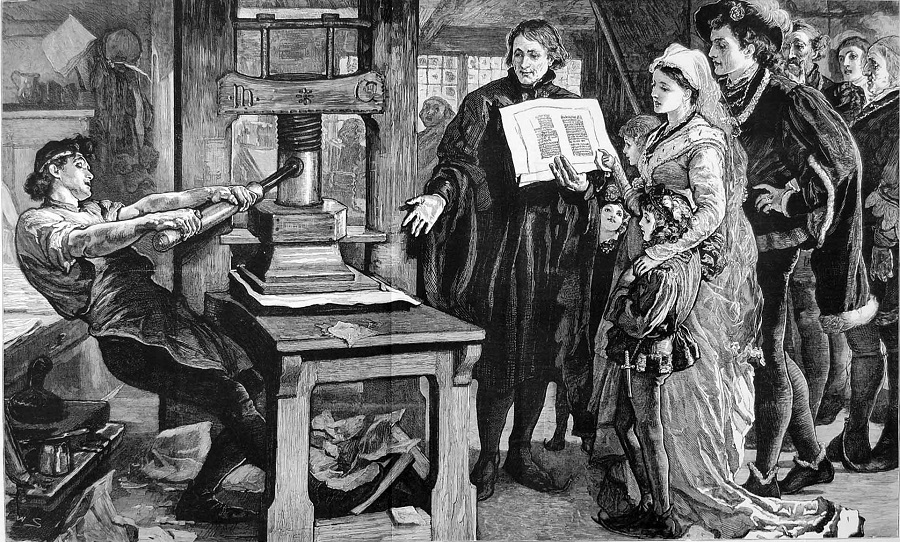

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The pretensions of Haarlem and Koster have for more than a century been a matter of fierce controversy; and there have been upward of one hundred and fifty volumes written for or against, without any approach to a satisfactory decision. This one thing is certain, that, whether or not we owe the first idea of movable type to Laurence Koster or to Haarlem, we do not owe to the period any very marked use of it; that was reserved for a later day.

There is a story current, dependent on the authority of Junius, that Koster’s principal workman, assumed to be Hans or John Faust — and some, to reconcile improbabilities, even say John Gutenberg — who had been sworn to secrecy, decamped one Christmas Eve, after the death of Koster, while the family were at church, taking with him types and printing apparatus and, after short sojourns at Amsterdam and Cologne, got to Mainz or Mayence with them, and there introduced printing. He is said by Junius to have printed, about the year 1442 — that is, two years after Koster’s death — the Doctrinale of Alexander Gallus and the Tracts of Peter of Spain, with the very types which Koster made use of in Haarlem; but as no volume of this kind has ever been discovered, nor any trace of one, the entire story is generally regarded as apocryphal. Laurence Koster died in 1440, at the age of seventy; therefore any printing attributed to him must be within that period.

What has hitherto been advanced proves only that mankind had walked for many centuries on the borders of the two great inventions, chalcography and typography, without having fully and practically discovered either of them.

We now come to the great epoch of printing — I mean the complete introduction, if not actually the first invention, of movable metal or fusile types. This took place at Mainz, in or before 1450, and the general consent of Europe assigns the credit of it to Gutenberg. Of a man who has conferred such vast obligations on all succeeding ages, it may be desirable to say a few words.

John Gutenberg was born at Mainz in 1397, of a patrician and rather wealthy family. He left his native city, it is said, because implicated in an insurrection of the citizens against the nobility, and settled at Strasburg, where, in 1427, we find him an established merchant, and sustaining a suit of breach of promise brought against him by a lady named Ann of the Iron Door, whom he afterward married. While resident here, and before 1439, his attention appears to have been actively directed to the art of printing, as we learn by a legal document of the time, found of late years in the archives of Strasburg. He is there stated to have entered into an engagement with three persons, named Dreizehn, Riffe, and Heilmann, to reveal to them “a secret art of printing which he had lately discovered,” and to take them into partnership for five years, upon the payment of certain sums.

The death of Dreizehn before he had paid up all his instalments led to a suit on the part of his relations, which ended in Gutenberg’s favor. In the course of the evidence one of the witnesses, a goldsmith, deposed to having received from Gutenberg three or four years previously — that is, about 1435 — upward of three hundred florins for materials used in printing. Other witnesses proved the anxiety that Gutenberg had shown to have four pages of type distributed which appear to have been screwed up in chase, and lying on a press on the deceased’s premises.

This would be evidence that Gutenberg had arrived at a knowledge of movable types, either of wood or metal, and probably of both, before 1440; and, had it not been for the rupture of the partnership before anything had been printed by the new process, Strasburg might have claimed the honor which is now given to Mainz.

Soon after this — it is supposed in 1444 — Gutenberg returned to his native city, by leave of the town council, which he was obliged to ask, bringing with him all his materials. In 1446 he entered into a partnership with John Faust — a wealthy and skilful goldsmith and engraver — who engaged, upon being taught the secrets of the art and admitted into a participation of the profits, to advance the necessary funds, which he did to the extent of two thousand two hundred florins. Goldsmiths, it should be borne in mind, were then the great artists in all kinds of metal work, and extremely skilful in modelling, engraving, and casting, which were exactly the arts required for type-founding.

The new partnership immediately commenced operations, hired a house called Zumjungen, and took into their employ Peter Schoeffer, who had been Faust’s apprentice, as their assistant. Faust is supposed to have employed himself in cutting the type, which is an extremely slow process, till Peter Schoeffer, afterward his son-in-law, suggested an improved mode of casting it in copper matrices struck by steel punches, pretty much in the same manner as was till recently practised throughout Europe. The firm had for some time previously adopted a method of casting type in moulds of plaster, which was a tedious process, as every letter required a new mould.

Although to Gutenberg are undoubtedly due all the main features of metal-type printing, yet we owe, perhaps, to the practical skill of Faust, and the taste of Schoeffer, who was an accomplished penman, the exquisite finish and perfection with which their first joint effort came forth to the world. This was a Latin Vulgate, printed in a large cut metal type, and commonly called the Mazarin Bible, because the first copy known to bibliographers was found in the library of Cardinal Mazarin. It consists of six hundred and forty-one leaves, forming two, sometimes four, large volumes in folio; some copies on paper of beautiful texture, some on vellum. It was without date or names of the printers, as it was evidently intended to present the appearance of a manuscript; but it is supposed, on good evidence, to have been printed between 1450 and 1455, and it is not improbable the volumes were all that time, that is, five years, and some say more, at press; for we know, by certain technicalities, that every page was printed off singly.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.