From Hudson to Peary three centuries extend. Through all these years the lure of the North has coaxed men on.

Continuing The Search for the North Pole,

our selection from The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 20 by Charles F. Horne published in 1914. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Search for the North Pole.

Place: The Northern Seas

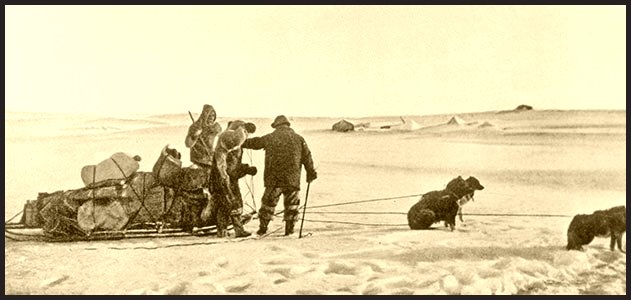

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

For a time after the disaster to Barents, the attempts to force the Northeast passage were abandoned. The Northwest route seemed the more promising. Various Englishmen had already attempted this, Frobisher, Gilbert, Davis among others. The latter of these, John Davis, made several successful voyages, successful in that he brought home wealth in whale oil and skins of seal and deer sufficient to satisfy the merchants who employed him. He thus created the still existing whaling and sealing industries along Greenland’s western coast. Davis died in the faith that he had discovered the Northwest passage. The natives of Greenland told him that there was a vast sea to the north and west of them, and he sailed up the strait which bears his name, confident he was at last upon the road to Asia (1585). He found land instead, and was the first to wander amid that vast mass of islands lying north of the American continent and west of Greenland. Then he returned to England with his spoils of whale and seal. But he returned again and yet again. On his third voyage (1587) he reached as far north upon the Greenland coast as the seventy-fifth parallel. Thence he sailed westward across the open waters, confident that here at last was the road to India. Ice and contrary winds drove him to the southward, and he reached the western islands again where he had reached them before. So, once more well paid for his voyage, he returned to England, meaning to venture by that passage again. But he never did, for the Spanish Armada drew Englishmen’s thoughts away from other things, and after that John Davis died.

Then came the most celebrated of early Arctic navigators, Henry Hudson. The fact that Hudson discovered the Hudson River while sailing in the service of Holland has resulted in his being thought of as at least partly a Dutchman. But Hudson was as thorough an Englishman as ever lived, and of his four notable voyages of discovery all but one sailed under England’s flag with English ships and crews.

With Hudson commences a new and important era in the history of Arctic exploration. On his very first voyage in 1607, he was sent out by the Muscovy Company of English merchants with the avowed purpose of sailing, if need be, across the Pole itself. That, asserted the merchants, might very well prove the shortest route to India. All earlier voyagers had sailed to west or east, only turning north as they were compelled to by the land that barred their way. Now, the north itself, the Pole itself was for the first time set as the explorers’ goal. For three centuries it continued to lure men on, as before the wealth of India had done, to suffering and death. So, Hudson, setting his ship’s prow straight to the north as once King Harold Hardrada had done, sought what fate, what goal, might come. Passing up Greenland’s eastern coast, he found the summer ice pack drifting down upon him, as it has drifted each summer for untold thousands of years. Hudson pushed his way among the floes, skirting the fringe of a huge unbroken ice pack which spread from Greenland to Spitzbergen barring his passage north. He reached latitude 8o° 23′, or perhaps even higher, being the first of the sons of Adam to cross the eightieth parallel, which lies less than seven hundred miles from the Pole. Even the Eskimos dwell less far north.

In a second voyage Hudson skirted the ice floe farther east, from Spitzbergen to Nova Zembla, but with no better success. By those routes at least, ships are barred forever from the Pole, by endless ice.

In his third voyage, sailing for Holland, Hudson sought a more southern passage, and hoped he had found it, when the swift tide swept him up the Hudson River, as through an ocean strait. Then came his last voyage with the awesome tragedy of his death. Again it was England which sent the resolute searcher forth. He would try the Northwest passage now. He did so, and entered the broad but shallow waters of Hudson’s Bay. Other explorers had passed its entrance; Frobisher had partly entered the opening strait. But none had gone far enough to recognize the existence of the great bay itself. Hudson sailed some hundred miles along its shores seeking a passage beyond. His crew grumbled, they desired to return home; but their leader persisted until winter caught them and they had to wait until spring upon that barren coast. They had not nearly sufficient provisions, so they subsisted on fish and birds and small game. Fortunately, they were not so far north as to be beyond the world of life. There were even trees around; and savages came to trade with the white men. In the spring Hudson set sail for home. He had, however, no provisions for the voyage. His men, already angered against him, were roused to desperation by a rumor that he had secreted the last of the bread for his own use. Some of the men mutinied, and madly selfish in their fear of starvation, committed the crime which has been rarest of all in the heroic history of the North. They seized Hudson by treachery, bound him, and forced him into the ship’s boat. With him they sent his young son and two men who persistently stayed faithful to him. Worse yet, they placed in the boat five of the crew who were sick and helpless. Then the mutineers sailed away. That tragically laden boat with its freight of dying bodies and loyal souls was never heard of again. Repeated search was made along the coasts of Hudson’s Bay; but the mutineers say that a storm swept over their course the next day, and presumably the frail boat sank. As for the mutineers, several, including the ringleaders, were slain in a battle with the natives before they reached the open ocean. The survivors, after suffering the last extremities of starvation, finally brought their ship back to Ireland. They were never punished for their share, or at least acquiescence, in the cowardly crime against Hudson and his loyal followers.

From Hudson to Peary three centuries extend. Through all these years the lure of the North has coaxed men on. Its grim and icy defiance has set stern hearts a-tingle with the longing for the grapple. By degrees, the truth was realized that no route through this deadly world of ice could ever be available for trade. But as mercantile reasons for venturing thither failed, scientific ones arose. Some material for mete orology, geology, and kindred studies could be gathered in the North. Chiefly, however, the North called to all men as a mystery. Perhaps its frigid heart might hold unbounded mineral wealth. Perhaps substances yet unknown to man there awaited his discovery. The extreme North might be less cold than the icy barriers which encircled it; the earth’s crust might be thinner there, internal heat might supply the needed warmth. Some theologians even imagined paradise might lie, unviolated, about the Pole. A mystery is ever something to be solved. The harder its achievement, the greater the glory of its attainment. So men strove, until to-day the mystery of the North is one no more; its glory has been garnered.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.