This series has eleven easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Printing From Antiquity

Introduction

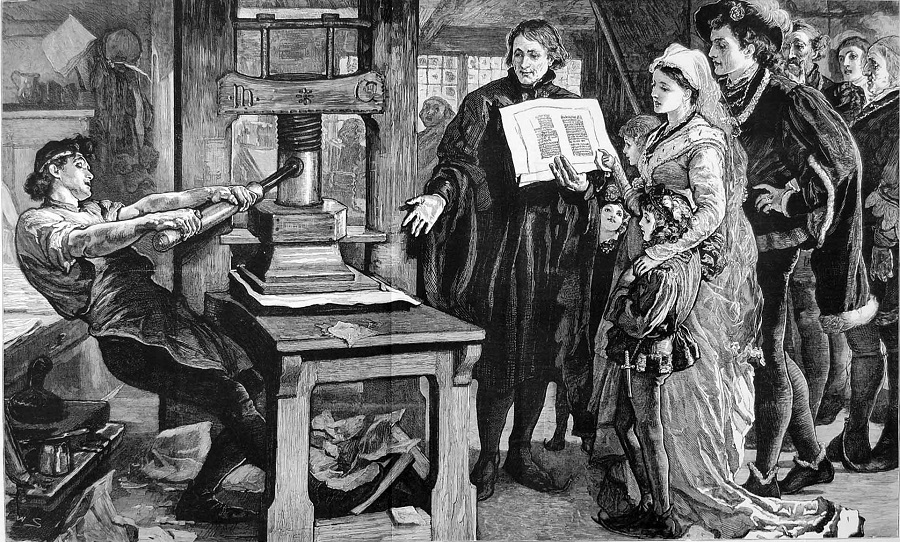

The invention of printing in Europe coincided with the rebirth of learning known as the Renaissance.

Bohn, in his survey of the origin and progress of modern printing, gives us a full and accurate account, from the earliest evidences and conjectures relating to antiquity to the latter part of the nineteenth century, confining himself, however, to European developments. Perhaps printing in its latest iteration may take the life of the human mind to a higher level.

This selection is from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Henry George Bohn (1796-1884) was is principally remembered for the Bohn’s Libraries which he inaugurated.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

“Nature does not advance by leaps,” says an old proverb; neither does her offspring, Art. All the great boons vouchsafed to man by a munificent providence are of gradual development; and though some may appear to have come upon us suddenly, reflection and inquiry will always show that they have had their previous stages.

Indeed, nothing in this great world which concerns the well-being of man takes place by accident, but is brought forward by divine will, precisely at the moment most suitable to our condition. So it was with astronomy, the mariner’s compass, the steam-engine, gas, the electric telegraph, and many other of those blessings which have progressed with civilization. The elements were there and known, but the time had not arrived for their fructification.

And so it is with printing: although its invention is placed in the middle of the fifteenth century, and almost the very year fixed, this can only be regarded as a matured stage of it. To illustrate this, I propose to begin with a cursory view of its primitive elements, of which the very first were no doubt initiative marks and numerals.

The use of numerals has been denominated “the foundation of all the arts of life”; and we know with certainty that several nations, and among them the Mexicans, had numerals before they were acquainted with letters. The first method of reckoning was with the fingers, but small stones were also used — hence the words “calculate” and “calculation,” which are derived from calculus, the Latin for a pebble-stone.

The Chinese counted for many years with notched sticks; and even in England, in comparatively modern times, accounts were kept by tallies, in which notches were cut alike in two parallel pieces of wood. Shakespeare alludes to “the score and the tally” in his Henry VI; and this mode of keeping accounts is still adopted by some of the bakers and dyers in Warwickshire and Cheshire. And tallies are occasionally produced in the small-debt courts, where they are admitted as authentic proofs of debt. Hence the origin and name of the “tally court of the exchequer.” The Peruvians, at the time they were conquered by Pizarro, counted with knotted strings.

After numerals, came picture-writing, hieroglyphics, and symbolic characters, such are were used by the Egyptians, the Chinese, and the Mexicans; which, however unconnected they may be with each other, are of the same general character. Indeed, the Chinese have never advanced beyond symbolic characters, of which it is said they have more than one hundred thousand combinations or varieties.

Rude as these conditions of humanity may seem, they are matched in modern England, even at a very recent date, if we may credit a well-known story: A rustic shopkeeper in a remote district, being unable to read or write, contrived to keep his accounts by picture-writing, and charged his customer, the miller, with a cheese instead of a grindstone, from having omitted to mark a hole in the centre.

After picture and symbolic writings would follow phonetic characters, or marks for sounds; that is, the alphabet. Even the alphabet, which in civilized countries has now existed for more than three thousand years, was perfected by degrees; for it has been clearly ascertained that the earliest known did not comprise more than one-half or, at most, two-thirds of the letters which eventually formed its complement. Thus, the Pelasgian alphabet, which is derived from the Phoenician, and is the parent of the Greek and Roman, consisted originally of only twelve or thirteen letters.

The invention of the alphabet, which, in a small number of elementary characters, is capable of six hundred and twenty sextillions of combinations, and of exhibiting to the sight the countless conceptions of the mind which have no corporeal forms, is so wonderful that great men of all ages have shrunk from accounting for it otherwise than as a boon of divine origin. This feeling is strengthened by the singular circumstance that so many alphabets bear a strong similarity to each other, however widely separated the countries in which they arose.

In Egypt the invention of the alphabet is by some ascribed to Syphoas, nearly two thousand years before the Christian era, but more commonly to Athotes, Thoth, or Toth, a deity always figured with the head of the ibis, and very familiar in Egyptian antiquities. Cadmus is accredited with having introduced it from Egypt into Greece about five centuries later.

From the alphabet the gradation is natural to compounds of letters and written language, and, though speech is one of the greatest gifts to man, it is writing which distinguishes him from the uncivilized savage. The practice of writing is of such remote antiquity that neither sacred nor profane authors can satisfactorily trace its origin. The philosopher may exclaim with the poet:

“Whence did the wondrous mystic art arise. Of painting speech and speaking to the eyes? That we, by tracing magic lines, are taught How both to color and embody thought?”

The earliest writing would probably have been with chalk, charcoal, slate, or perhaps sand, as children from time immemorial have been taught to read and write in India. The Romans used white walls for writing inscriptions on, in red chalk — answering the purpose of our posting-bills — of which several instances were found on the walls of Pompeii. Plutarch informs us that tradesmen wrote in some such manner over their doors, and that auction bills ran thus:

“Julius Proculus will this day have an auction of his superfluous goods, to pay his debts.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.