Before the commencement of the sixteenth century, that is, within forty or fifty years of the invention of printing with movable type, upward of twenty thousand volumes had issued from at least a thousand different presses.

Continuing Early History of Printing,

our selection from Origin and Progress of Printing by Henry George Bohn published in 1857. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Early History of Printing.

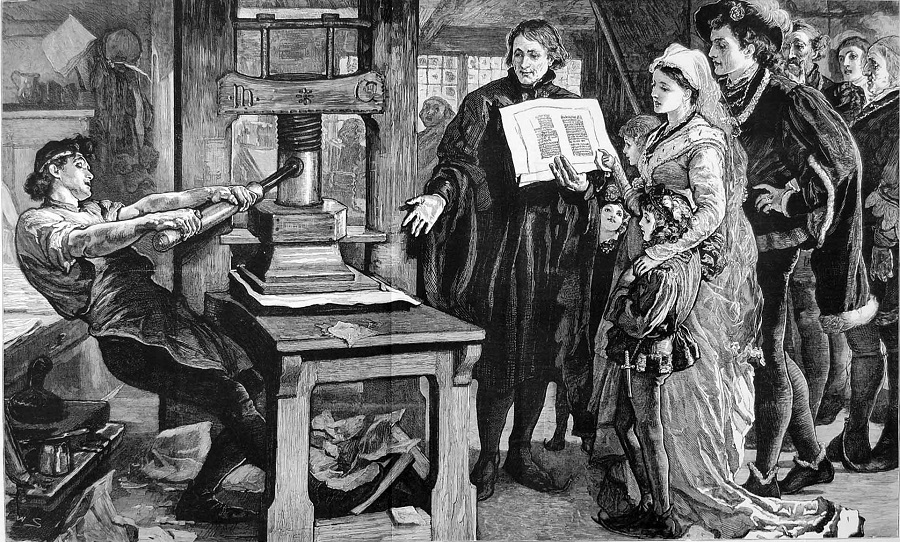

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At this critical period, when the art was reaching its zenith, the operations of the Mainz printers were suddenly brought to a standstill by the siege and capture of the city in 1462. The occasion of this was a fierce dispute between the Pope and the people as to who had the right of appointment to the archbishopric, lately become vacant. The original hive of workmen dispersed to other states, and by degrees the mysteries of the art became spread over the civilized world. Such, indeed, was the fame printing had acquired, and its manifest importance, that every crowned head sought to introduce it into his kingdom, and welcomed the fugitives. Within a few years of this period the art had been carried by the scattered German workmen into Italy, France, Spain, and Switzerland; and before the close of the fifteenth century it was practiced in more than two hundred twenty different places.

Before entering upon the history of printing in England, I will take leave to call your attention to a few prominent facts connected with its progress abroad, as well as to some points of its early condition which could not be conveniently introduced in chronological order. All the books printed previously to 1465 are in the Gothic, or black letter, which still remained the favorite in Germany and the Low Countries long after the Italians introduced their beautiful Roman letter. The first books in which any Greek type occurs are Cicero’s Offices, printed by Faust and Schoeffer in 1465, directly after the resumption of their establishment; and Lactantius, printed the same year by Sweynheim and Pannartz, in the monastery of Soubiaco at Rome. The first book printed entirely in Greek was Constantine Lascar’s Greek Grammar, Milan, 1476.

One of the earliest of the Italian books, and, to use the words of Dr. Dibdin, perhaps the most notorious volume in existence, was the celebrated Boccaccio, printed at Venice by Valdarfer in 1471. This book deserves particular mention, because of an extraordinary contest which once took place for its possession between two wealthy bibliomaniacs. It was a small black-letter folio, in faded yellow morocco, and supposed to be unique. Its history is this: In the early part of the eighteenth century it had come accidentally into the possession of a London bookseller, who successively offered it to Harley, Earl of Oxford, and to Lord Sunderland; then the two principal collectors, for one hundred guineas; but both were staggered at the price and higgled about the purchase. An ancestor of the late Duke of Roxburghe, whom nobody dreamed of as a collector, hearing of the book, secured it, and then invited the two noblemen to dinner, with the view of parading his trophy. In due course he led the conversation to the book, and, after letting them expatiate on its rarity, told them he thought he had a copy in his bookcase, which they emphatically declared to be impossible, and challenged him to produce it. On producing the book, about the purchase of which they had only been temporizing, they were not a little chagrined.

This same copy made its appearance again, half a century later, at the Duke of Roxburghe’s sale in 1812, a time when bibliomania was at its height. Loud notes of preparation foretold that it would sell for a considerable sum; five hundred and even one thousand guineas were guessed, as it was known that Lord Spencer, the Duke of Devonshire, and the Marquis of Blandford were all bent on its possession, but nobody anticipated the extravagant sum it was to realize. After a very spirited competition, it was knocked down to the Marquis of Blandford for two thousand sixty pounds. This book was resold at the Marquis of Blandford’s sale, in 1819, for eight hundred seventy-five guineas, and passed to Lord Spencer, in whose extraordinary library it now reposes.

Before the commencement of the sixteenth century, that is, within forty or fifty years of the invention of printing with movable type, upward of twenty thousand volumes had issued from at least a thousand different presses. All the principal Latin classics, many of the Greek, and upward of two hundred fifty editions of the Bible, or parts of the Bible, had appeared.

One of the most active and enterprising of the early printers was Anthony Koburger of Nuremberg, an accomplished scholar, who began there in 1472, and before the year 1500 had printed thirteen large editions of the Bible in folio, and a prodigious number of other books. He kept twenty-four presses at work, employing one hundred workmen, and had sixteen shops for the sale of books in the principal cities of Germany, besides factors and agents all over Europe. He printed, in 1493, that grand volume, the Nuremberg Chronicle, which is illustrated with upward of one thousand woodcuts by Michael Wohlgemuth, the master of Albert Dürer, and is curious as being one of the first books in which cross-hatchings occur in wood-engraving.

The sixteenth century opened with another invention in type, the Italic, which was beautifully exemplified in a pocket edition of Vergil, the first of a portable series of classical works commenced in 1501 at Venice by the celebrated Aldus Manutius, who, after some years of preparation, had entered actively on his career as a printer in 1494, and deservedly ranks as one of the best scholars of any age.

Then came the Giunti, the learned family of the Stephenses, of whom Robert is accredited as the author of the present divisions of our New Testament into chapters, and Henry, author of the great Greek Thesaurus, the most valuable Greek lexicon ever published. To the opprobrium of the age, he died in an almshouse.

Among many others immortalized by their successful contributions to the great cause we must not forget the Plantins, whose memories are still so cherished at Antwerp that their printing establishment remains to this day untouched, just as it was left two centuries ago, with all the freshness of a chamber in Pompeii, the type and chases of their famous Polyglot lying about, as if the workmen had but just left the office.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.