This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Nobility Forms League Against King John.

Introduction

While the Great Charter is criticized for granting rights to the aristocracy and not to the commoners, its true legacy is that it marks the transition from the age of traditional rights to the age of written legislation, — of parliaments and statutes, which was soon to come.

King John, the villain of the Robin Hood legends, had oppressed England in three ways: (1) the remaining oppressions of the Norman kings after the Conquest; (2) the necessity of raising taxes and other measures for wars against France; and (3) his own odious personal and official conduct.

When William the Conqueror became king, he greatly curtailed the ancient liberties of the Anglo-Saxons. In fact, the whole English people were reduced to a state of vassalage, which for the majority closely bordered upon actual slavery. Even the proud Norman barons themselves submitted to a kingly prerogative more absolute than was usual in feudal governments. In short, Norman rule was a real tyranny — even for those times.

King John’s wars with France were disastrous. He never stopped preparations for another war.

Individually, his personal scandals could have been tolerated; his constant demands of war measures could have been tolerated (if there were any success); indeed, the Norman tyranny had in fact been tolerated since 1066. It was the combination of all these together which brought on the crisis.

This selection is from History of England From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688 by David Hume published in 1762. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

David Hume (1711-1776) was the celebrated philosopher, historian, and writer.

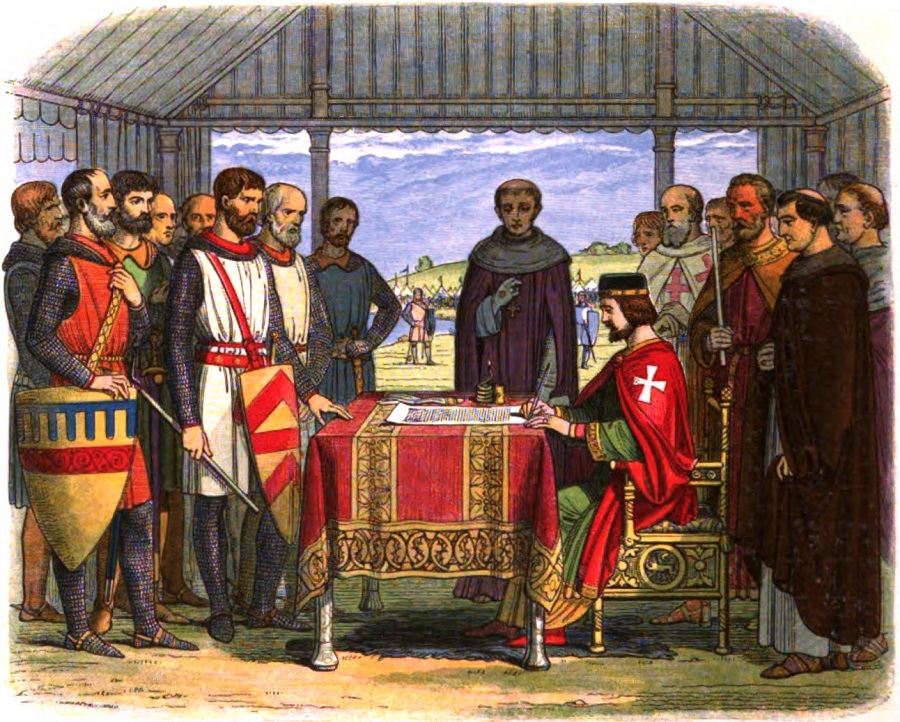

Time: June 19, 1215

Place: Runnymede Field, on the south bank of the Thames River

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The effect of John’s lawless practices had already appeared in the general demand made by the barons of a restoration of their privileges; and after he had reconciled himself to the Pope, by abandoning the independence of the kingdom, he appeared to all his subjects in so mean a light that they universally thought they might with safety and honor insist upon their pretensions.

But nothing forwarded this confederacy so much as the concurrence of Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury; a man whose memory, though he was obtruded on the nation by a palpable encroachment of the see of Rome, ought always to be respected by the English. This prelate — whether he was moved by the generosity of his nature and his affection to public good or had entertained an animosity against John, on account of the long opposition made by that prince to his election, or thought that an acquisition of liberty to the people would serve to increase and secure the privileges of the Church — had formed the plan of reforming the government. In a private meeting of some principal barons at London, he showed them a copy of Henry I’s charter, which, he said, he had happily found in a monastery; and he exhorted them to insist on the renewal and observance of it. The barons swore that they would sooner lose their lives than depart from so reasonable a demand.

The confederacy began now to spread wider, and to comprehend almost all the barons in England; and a new and more numerous meeting was summoned by Langton at St. Edmundsbury, under color of devotion. He again produced to the assembly the old charter of Henry; renewed his exhortations of unanimity and vigor in the prosecution of their purpose; and represented, in the strongest colors, the tyranny to which they had so long been subjected, and from which it now behooved them to free themselves and their posterity. The barons, inflamed by his eloquence, incited by the sense of their own wrongs, and encouraged by the appearance of their power and numbers, solemnly took an oath, before the high altar, to adhere to each other, to insist on their demands, and to make endless war on the King till he should submit to grant them. They agreed that, after the festival of Christmas, they would prefer in a body their common petition; and in the meantime they separated, after mutually engaging that they would put themselves in a posture of defense, would enlist men and purchase arms, and would supply their castles with the necessary provisions.

The barons appeared in London on the day appointed, and demanded of the King, that, in consequence of his own oath before the primate, as well as in deference to their just rights, he should grant them a renewal of Henry’s charter, and a confirmation of the laws of St. Edward. The King, alarmed with their zeal and unanimity, as well as with their power, required a delay; promised that, at the festival of Easter, he would give them a positive answer to their petition; and offered them the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of Ely, and the Earl of Pembroke as sureties for his fulfilling this engagement. The barons accepted of the terms, and peaceably returned to their castles.

During this interval, John, in order to break or subdue the league of his barons, endeavored to avail himself of the ecclesiastical power, of whose influence he had, from his own recent misfortunes, had such fatal experience. He granted to the clergy a charter, relinquishing forever that important prerogative for which his father and all his ancestors had zealously contended; yielding to them the free election on all vacancies; reserving only the power to issue a congé d’élire, and to subjoin a confirmation of the election; and declaring that, if either of these were withheld, the choice should nevertheless be deemed just and valid.

He made a vow to lead an army into Palestine against the infidels, and he took on him the cross, in hopes that he should receive from the Church that protection which she tendered to everyone that had entered into this sacred and meritorious engagement. And he sent to Rome his agent, William de Mauclerc, in order to appeal to the Pope against the violence of his barons, and procure him a favorable sentence from that powerful tribunal. The barons, also, were not negligent on their part in endeavoring to engage the Pope in their interests. They dispatched Eustace de Vescie to Rome; laid their case before Innocent as their feudal lord, and petitioned him to interpose his authority with the King, and oblige him to restore and confirm all their just and undoubted privileges.

Innocent beheld with regret the disturbances which had arisen in England, and was much inclined to favor John in his pretensions. He had no hopes of retaining and extending his newly acquired superiority over that kingdom, but by supporting so base and degenerate a prince, who was willing to sacrifice every consideration to his present safety; and he foresaw that if the administration should fall into the hands of those gallant and high-spirited barons, they would vindicate the honor, liberty, and independence of the nation, with the same ardor which they now exerted in defense of their own. He wrote letters, therefore, to the prelates, to the nobility, and to the King himself. He exhorted the first to employ their good offices in conciliating peace between the contending parties and putting an end to civil discord. To the second he expressed his disapprobation of their conduct in employing force to extort concessions from their reluctant sovereign; the last he advised to treat his nobles with grace and indulgence, and to grant them such of their demands as should appear just and reasonable.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.