The King, marching through the whole extent of England, from Dover to Berwick, laid the provinces waste on each side of him.

Continuing The Magna Carta Signed,

our selection from History of England From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688 by David Hume published in 1762. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Magna Carta Signed.

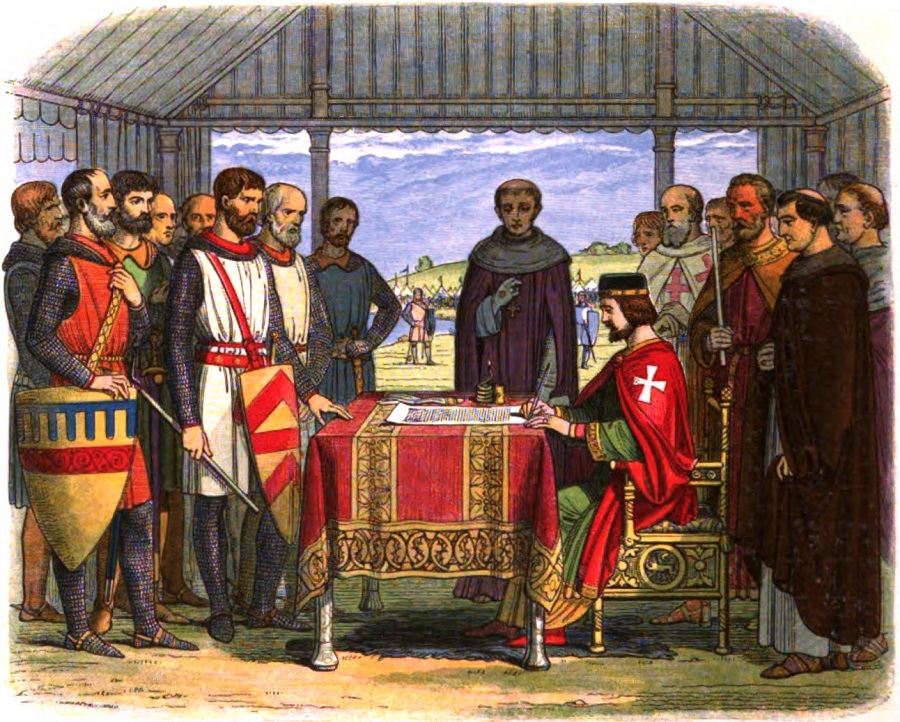

Time: June 19, 1215

Place: Runnymede Field, on the south bank of the Thames River

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

King John grew sullen, silent, and reserved; he shunned the society of his courtiers and nobles; he retired into the Isle of Wight, as if desirous of hiding his shame and confusion; but in this retreat he meditated the most fatal vengeance against all his enemies. He secretly sent abroad his emissaries to enlist foreign soldiers, and to invite the rapacious Brabancons into his service, by the prospect of sharing the spoils of England and reaping the forfeitures of so many opulent barons who had incurred the guilt of rebellion by rising in arms against him. And he dispatched a messenger to Rome, in order to lay before the Pope the Great Charter, which he had been compelled to sign, and to complain, before that tribunal, of the violence which had been imposed upon him.

Innocent, considering himself as feudal lord of the kingdom, was incensed at the temerity of the barons, who, though they pretended to appeal to his authority, had dared, without waiting for his consent, to impose such terms on a prince, who, by resigning to the Roman pontiff his crown and independence, had placed himself immediately under the papal protection. He issued, therefore, a bull, in which, from the plenitude of his apostolic power, and from the authority which God had committed to him, to build and destroy kingdoms, to plant and overthrow, he annulled and abrogated the whole charter, as unjust in itself, as obtained by compulsion, and as derogatory to the dignity of the apostolic see. He prohibited the barons from exacting the observance of it; he even prohibited the King himself from paying any regard to it; he absolved him and his subjects from all oaths which they had been constrained to take to that purpose; and he pronounced a general sentence of excommunication against everyone who should persevere in maintaining such treasonable and iniquitous pretensions.

The King, as his foreign forces arrived along with this bull, now ventured to take off the mask; and, under sanction of the Pope’s decree, recalled all the liberties which he had granted to his subjects, and which he had solemnly sworn to observe. But the spiritual weapon was found upon trial to carry less force with it than he had reason from his own experience to apprehend. The Primate refused to obey the Pope in publishing the sentence of excommunication against the barons; and though he was cited to Rome, that he might attend a general council there assembled, and was suspended, on account of his disobedience to the Pope and his secret correspondence with the King’s enemies; though a new and particular sentence of excommunication was pronounced by name against the principal barons — John still found that his nobility and people, and even his clergy, adhered to the defense of their liberties and to their combination against him; the sword of his foreign mercenaries was all he had to trust to for restoring his authority.

The barons, after obtaining the Great Charter, seem to have been lulled into a fatal security, and to have taken no rational measures, in case of the introduction of a foreign force, for reassembling their armies. The King was, from the first, master of the field, and immediately laid siege to the castle of Rochester, which was obstinately defended by William de Albiney, at the head of a hundred and forty knights with their retainers but was at last reduced by famine. John, irritated with the resistance, intended to have hanged the governor and all the garrison; but on the representation of William de Mauleon, who suggested to him the danger of reprisals, he was content to sacrifice, in this barbarous manner, the inferior prisoners only. The captivity of William de Albiney, the best officer among the confederated barons, was an irreparable loss to their cause; and no regular opposition was thenceforth made to the progress of the royal arms. The ravenous and barbarous mercenaries, incited by a cruel and enraged prince, were let loose against the estates, tenants, manors, houses, parks of the barons, and spread devastation over the face of the kingdom.

Nothing was to be seen but the flames of villages, and castles reduced to ashes, the consternation and misery of the inhabitants, tortures exercised by the soldiery to make them reveal their concealed treasures, and reprisals no less barbarous, committed by the barons and their partisans on the royal demesnes, and on the estates of such as still adhered to the Crown. The King, marching through the whole extent of England, from Dover to Berwick, laid the provinces waste on each side of him, and considered every estate which was not his immediate property as entirely hostile and the object of military execution. The nobility of the North in particular, who had shown greatest violence in the recovery of their liberties, and who, acting in a separate body, had expressed their discontent even at the concessions made by the Great Charter, as they could expect no mercy, fled before him with their wives and families, and purchased the friendship of Alexander, the young King of Scots, by doing homage to him.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.