John seemed to submit passively to all these regulations, however injurious to majesty.

Continuing The Magna Carta Signed,

our selection from History of England From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688 by David Hume published in 1762. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Magna Carta Signed.

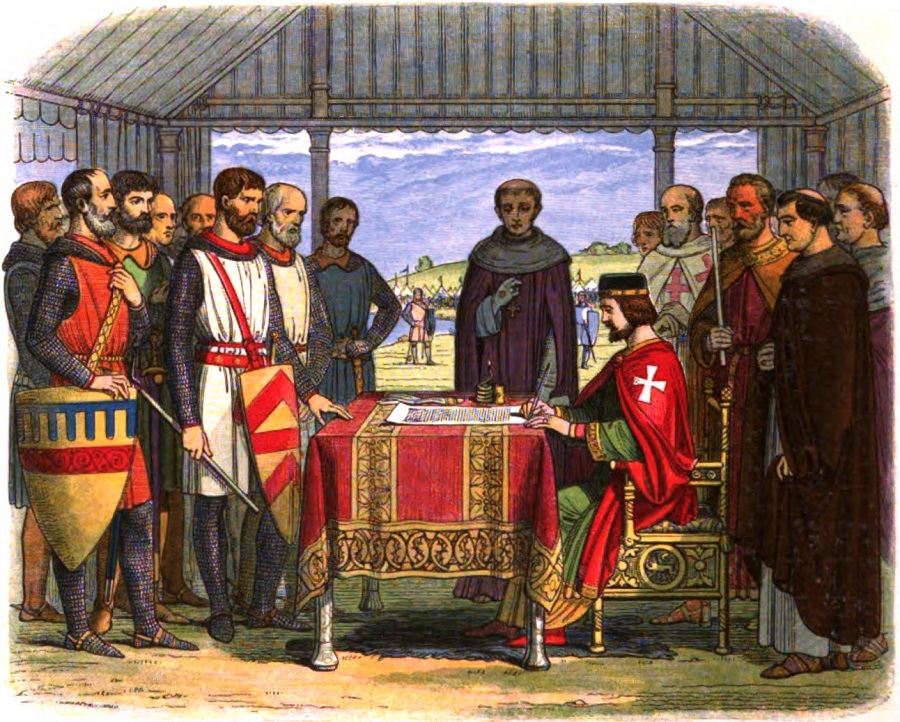

Time: June 19, 1215

Place: Runnymede Field, on the south bank of the Thames River

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It must be confessed that the former articles of the Great Charter contain such mitigations and explanations of the feudal law as are reasonable and equitable; and that the latter involve all the chief outlines of a legal government, and provide for the equal distribution of justice and free enjoyment of property; the great objects for which political society was at first founded by men, which the people have a perpetual and unalienable right to recall, and which no time, nor precedent, nor statute, nor positive institution ought to deter them from keeping ever uppermost in their thoughts and attention.

Though the provisions made by this charter might, conformably to the genius of the age, be esteemed too concise, and too bare of circumstances to maintain the execution of its articles, in opposition to the chicanery of lawyers, supported by the violence of power, time gradually ascertained the sense of all the ambiguous expressions; and those generous barons, who first extorted this concession, still held their swords in their hands, and could turn them against those who dared, on any pretense, to depart from the original spirit and meaning of the grant. We may now, from the tenor of this charter, conjecture what those laws were of King Edward, which the English nation, during so many generations, still desired, with such an obstinate perseverance, to have recalled and established. They were chiefly these latter articles of Magna Charta; and the barons who, at the beginning of these commotions, demanded the revival of the Saxon laws, undoubtedly thought that they had sufficiently satisfied the people by procuring them this concession, which comprehended the principal objects to which they had so long aspired.

But what we are most to admire is the prudence and moderation of those haughty nobles themselves who were enraged by injuries, inflamed by opposition, and elated by a total victory over their sovereign. They were content, even in this plenitude of power, to depart from some articles of Henry I’s charter, which they made the foundation of their demands, particularly from the abolition of wardships, a matter of the greatest importance; and they seem to have been sufficiently careful not to diminish too far the power and revenue of the crown. If they appear, therefore, to have carried other demands to too great a height, it can be ascribed only to the faithless and tyrannical character of the King himself, of which they had long had experience, and which they foresaw would, if they provided no further security, lead him soon to infringe their new liberties, and revoke his own concessions. This alone gave birth to those other articles, seemingly exorbitant, which were added as a rampart for the safeguard of the Great Charter.

The barons obliged the King to agree that London should remain in their hands, and the Tower be consigned to the custody of the Primate till the 15th of August ensuing or till the execution of the several articles of the Great Charter. The better to insure the same end, he allowed them to choose five-and-twenty members from their own body as conservators of the public liberties; and no bounds were set to the authority of these men either in extent or duration. If any complaint were made of a violation of the charter, whether attempted by the king, justiciaries, sheriffs, or foresters, any four of these barons might admonish the king to redress the grievance; if satisfaction were not obtained, they could assemble the whole council of twenty-five; who, in conjunction with the great council, were empowered to compel him to observe the charter, and, in case of resistance, might levy war against him, attack his castles, and employ every kind of violence except against his royal person and that of his queen and children.

All men throughout the kingdom were bound, under the penalty of confiscation, to swear obedience to the twenty-five barons; and the freeholders of each county were to choose twelve knights, who were to make report of such evil customs as required redress, conformably to the tenor of the Great Charter.* The names of those conservators were: the Earls of Clare, Albemarle, Gloucester, Winchester, Hereford; Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk; Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford; William Mareschal, the younger; Robert Fitz-Walter, Gilbert de Clare, Eustace de Vescey, Gilbert Delaval, William de Moubray, Geoffrey de Say, Roger de Mombezon, William de Huntingfield; Robert de Ros, the Constable of Chester; William de Aubenie, Richard de Perci, William Malet, John Fitz-Robert, William de Lanvalay, Hugh de Bigod, and Roger de Montfichet. These men were, by this convention, really invested with the sovereignty of the kingdom; they were rendered coordinate with the King, or rather superior to him, in the exercise of the executive power; and as there was no circumstance of government which, either directly or indirectly, might not bear a relation to the security or observance of the Great Charter, there could scarcely occur any incident in which they might not lawfully interpose their authority.

[* This seems a very strong proof that the house of commons was not then in being; otherwise the knights and burgesses from the several counties could have given in to the lords a list of grievances, without so unusual an election.]

John seemed to submit passively to all these regulations, however injurious to majesty. He sent writs to all the sheriffs ordering them to constrain everyone to swear obedience to the twenty-five barons; he dismissed all his foreign forces; he pretended that his government was thenceforth to run in a new tenor and be more indulgent to the liberty and independence of his people. But he only dissembled till he should find a favorable opportunity for annulling all his concessions. The injuries and indignities which he had formerly suffered from the Pope and the King of France, as they came from equals or superiors, seemed to make but small impression on him; but the sense of this perpetual and total subjection under his own rebellious vassals sank deep in his mind; and he was determined, at all hazards, to throw off so ignominious a slavery.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.