Today’s installment concludes The Magna Carta Signed,

our selection from History of England From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688 by David Hume published in 1762.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Magna Carta Signed.

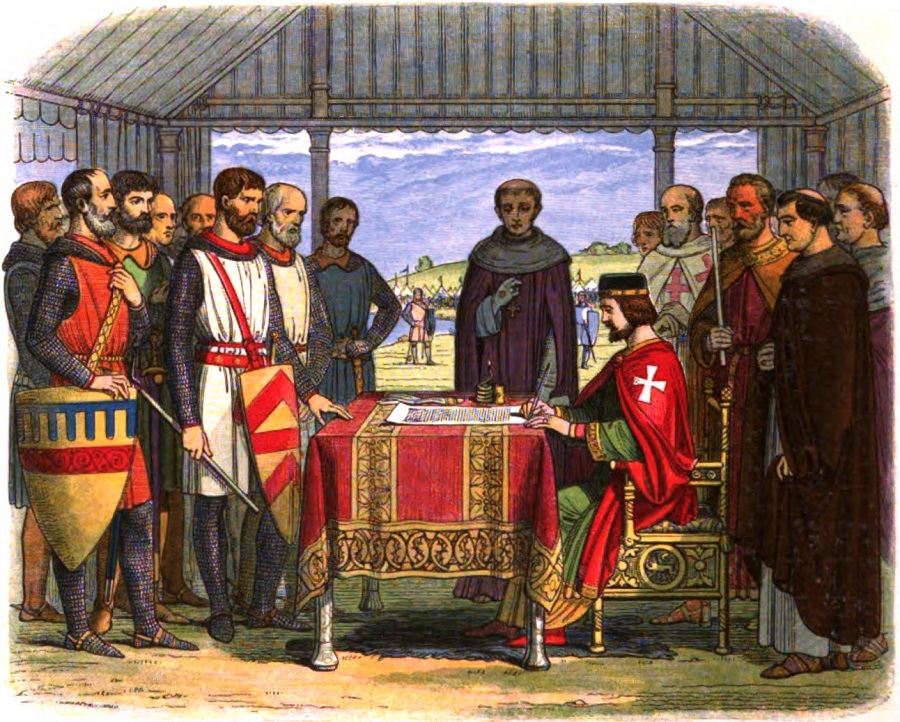

Time: June 19, 1215

Place: Runnymede Field, on the south bank of the Thames River

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The barons, reduced to this desperate extremity, and menaced with the total loss of their liberties, their properties, and their lives, employed a remedy no less desperate; and making applications to the court of France, they offered to acknowledge Louis, the eldest son of Philip, for their sovereign, on condition that he would afford them protection from the violence of their enraged Prince. Though the sense of the common rights of mankind, the only rights that are entirely indefeasible, might have justified them in the deposition of their King, they declined insisting before Philip on a pretension which is commonly so disagreeable to sovereigns and which sounds harshly in their royal ears. They affirmed that John was incapable of succeeding to the crown, by reason of the attainder passed upon him during his brother’s reign, though that attainder had been reversed, and Richard had even, by his last will, declared him his successor. They pretended that he was already legally deposed by sentence of the peers of France, on account of the murder of his nephew, though that sentence could not possibly regard anything but his transmarine dominions, which alone he held in vassalage to that crown. On more plausible grounds they affirmed that he had already deposed himself by doing homage to the Pope, changing the nature of his sovereignty, and resigning an independent crown for a fee under a foreign power. And as Blanche of Castile, the wife of Louis, was descended by her mother from Henry II, they maintained, though many other princes stood before her in the order of succession, that they had not shaken off the royal family in choosing her husband for their sovereign.

Philip was strongly tempted to lay hold on the rich prize which was offered to him. The legate menaced him with interdicts and excommunications if he invaded the patrimony of St. Peter or attacked a prince who was under the immediate protection of the holy see; but as Philip was assured of the obedience of his own vassals, his principles were changed with the times, and he now undervalued as much all papal censures as he formerly pretended to pay respect to them. His chief scruple was with regard to the fidelity which he might expect from the English barons in their new engagements, and the danger of entrusting his son and heir into the hands of men who might, on any caprice or necessity, make peace with their native sovereign, by sacrificing a pledge of so much value. He therefore exacted from the barons twenty-five hostages of the most noble birth in the kingdom; and having obtained this security, he sent over first a small army to the relief of the confederates; then more numerous forces, which arrived with Louis himself at their head.

The first effect of the young Prince’s appearance in England was the desertion of John’s foreign troops, who, being mostly levied in Flanders and other provinces of France, refused to serve against the heir of their monarchy. The Gascons and Poictevins alone, who were still John’s subjects, adhered to his cause; but they were too weak to maintain that superiority in the field which they had hitherto supported against the confederated barons. Many considerable noblemen deserted John’s party — the earls of Salisbury, Arundel, Warrenne, Oxford, Albemarle, and William Mareschal the Younger. His castles fell daily into the hands of the enemy; Dover was the only place which, from the valor and fidelity of Hubert de Burgh, the governor, made resistance to the progress of Louis; and the barons had the melancholy prospect of finally succeeding in their purpose, and of escaping the tyranny of their own King, by imposing on themselves and the nation a foreign yoke.

But this union was of short duration between the French and English nobles; and the imprudence of Louis, who on every occasion showed too visible a preference to the former, increased their jealousy which it was so natural for the latter to entertain in their present situation. The Viscount of Melun, too, it is said, one of his courtiers, fell sick at London, and, finding the approaches of death, he sent for some of his friends among the English barons, and, warning them of their danger, revealed Louis’s secret intentions of exterminating them and their families as traitors to their Prince, and of bestowing their estates and dignities on his native subjects, in whose fidelity he could more reasonably place confidence. This story, whether true or false, was universally reported and believed; and, concurring with other circumstances which rendered it credible, did great prejudice to the cause of Louis. The Earl of Salisbury and other noblemen deserted again to John’s party; and as men easily change sides in civil war, especially where their power is founded on a hereditary and independent authority and is not derived from the opinion and favor of the people, the French Prince had reason to dread a sudden reverse of fortune.

The King was assembling a considerable army with a view of fighting one great battle for his crown; but passing from Lynne to Lincolnshire, his road lay along the sea-shore, which was overflowed at high water; and not choosing the proper time for his journey, he lost in the inundation all his carriages, treasure, baggage, and regalia. The affliction of this disaster, and vexation from the distracted state of his affairs, increased the sickness under which he then labored; and though he reached the castle of Newark, he was obliged to halt there, and his distemper soon after put an end to his life, in the forty-ninth year of his age and eighteenth of his reign, and freed the nation from the dangers to which it was equally exposed by his success or by his misfortunes.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Magna Carta Signed by David Hume from his book History of England From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688 published in 1762. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Magna Carta Signed here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.