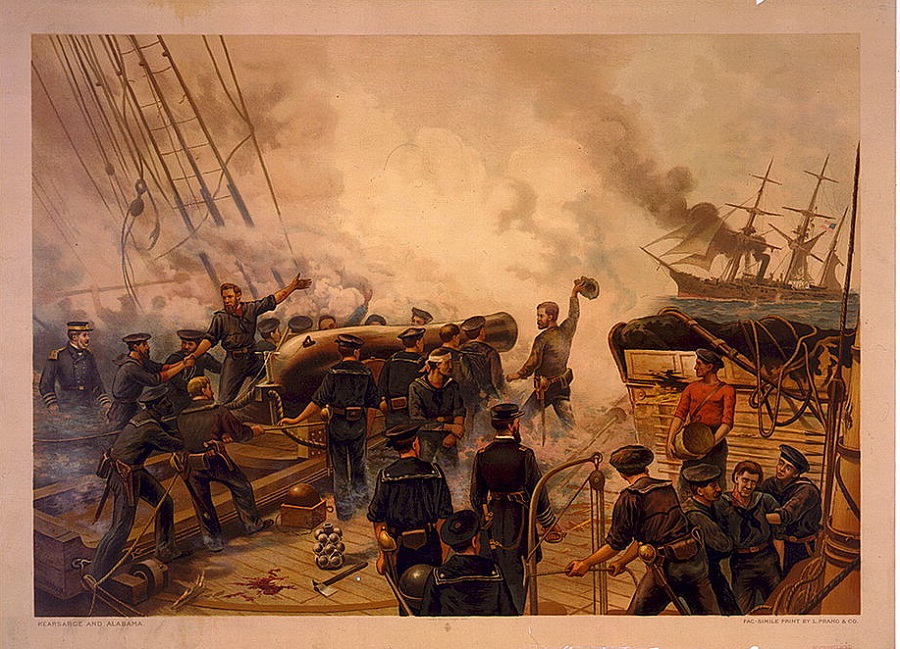

In the engagement the Alabama fought seven guns, and the Kearsarge five, both exercising the starboard battery, until the Alabama winded, using her port battery, with one gun, and another, shifted over.

Continuing The USS Kearsarge Versus the CSS Alabama.

Today is our final installment from John Ancrum Winslow and then we begin the second part of the series with Raphael Semmes. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The USS Kearsarge Versus the CSS Alabama.

Time: June 19, 1864

Place: English Channel off Cherborg, France

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The fire of the Alabama, though it is said that she discharged three hundred seventy or more shell and shot, was not of serious damage to the Kearsarge. Thirteen or fourteen of these had taken effect in and about the hull, and sixteen or seventeen about the mast and rigging. The casualties were small, only three persons having been wounded, yet it is a matter of surprise that so few were injured, considering the number of projectiles that came aboard. Two shots passed through the port in which the thirty-twos were placed, with men stationed thickly around them, one taking effect in the hammock-netting, and the other going through the port on the opposite side; yet no one was hit, the captain of one of the guns being only knocked down by the wind of the shot, as was supposed. The fire of the Kearsarge, although only one hundred seventy-three projectiles had been discharged, according to the prisoners’ accounts, was terrific. One shot alone had killed or wounded eighteen men and disabled the gun; another had entered the coal-bunkers, exploding, and completely blocked up the engine-room; and Captain Semmes says that shot and shell had taken effect in the sides of his vessel, tearing large holes by explosion, and his men were everywhere knocked down.

Of the casualties on the Alabama no correct account can be given. One hundred fifteen persons reached the shore, either in England or in France, after the action. It is known that the Alabama carried a crew, officers and men, of about one hundred fifty into Cherbourg, and that while in the Southern Ocean her complement was about one hundred seventy, but desertions had reduced this figure.

The prisoners say that a number of men came on board at Cherbourg; and, the night before the action, boats were going to and fro, and in the morning strange men were seen, who were stationed as captains of the guns. Among these there was one lieutenant (Sinclair), who joined her at Cherbourg.

The Alabama had been five days in preparation; she had taken in three hundred fifty tons of coal, which brought her down into the water. The Kearsarge had only one hundred twenty tons in; but, as an offset to this, her sheet-chains were stowed outside, stopped up and down, as an additional preventive and protection to her more empty bunkers. The number of the crew of the Kearsarge, including officers and sick men, was one hundred sixty-three, and her battery numbered seven guns —- two 11-inch, one 30-pounder rifle, and four light 32-pounder guns. The battery of the Alabama numbered eight guns. In the engagement the Alabama fought seven guns, and the Kearsarge five, both exercising the starboard battery, until the Alabama winded, using her port battery, with one gun, and another, shifted over.

Now we begin the second the second part of our series with our selection from the Official Report of Raphael Semmes. The selection is presented in 2.5 easy 5 minute installments.

Raphael Semmes (1809-1877) was the captain of the CSS Alabama.

[Semmes, in this account, speaks of himself in the third person.-E.D.]

It has been denied that the captain of the Kearsarge sent a challenge to the Alabama. Captain Semmes, indeed, says nothing of it himself. What the Kearsarge did -— and with a particular object, there cannot be a doubt -— was, as recorded, to enter the breakwater at the east end, and “at about 11 a.m. on Tues day she passed through the west end without anchoring.” These are the words of a French naval captain, who speaks of what he saw. Few will deny that among brave men this would be considered something equivalent to a challenge. It was more than a challenge -— it was a defiance. The officer we have quoted adds that “anyone could then see her outside protection.”

It is easy to see everything after the event. The Kearsarge looked bulky in her middle section to an inspecting eye; but she was very low in the water, and that she was armed to resist shot and shell it was impossible to discern. It is distinctly averred by the officers of the Alabama that from their vessel the armor of the Kearsarge could not be distinguished. There were many reports abroad that she was protected on her sides in some peculiar way; but all were various and indistinct, and to a practical judgment untrustworthy. Moreover, a year previous to this meeting, the Kearsarge had lain at anchor close under the critical eye of Captain Semmes. He had on that occasion seen that his enemy was not artificially defended. He believes now that the reports of her plating and armor were so much harbor gossip, of which during his cruises he had experienced enough.

Now the Kearsarge was an old enemy, constantly in pursuit, and her appearance produced, as Captain Semmes has written, great excitement on board the Alabama. For two years the officers and men of the Alabama had been homeless, and without a prospect of reaching home. They had been constantly crowded with prisoners, who devoured their provender —- of which they never had any but a precarious supply. Their stay in any neutral harbor was necessarily short. They were fortified by the assurance of a mighty service done to their country. They knew that they inflicted tremendous damage upon their giant foe. But their days were wretched; their task was sickening. In addition, they read of the reproaches heaped upon them by comfortable shoremen. They were called pirates. The execrations of certain of the French and English and of all the United States press sounded in their ears across the ocean; but from their own country they heard little. The South was a sealed land in comparison with the rest of the world. Opinion spoke loudest in Europe; and though they knew that they were faithfully and gallantly serving their country in her sore need, the absence of any immediate comfort, physical or moral, made them keenly sensitive to virulent criticism.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

John Ancrum Winslow began here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.