It will be necessary that those Ministers and Governors who do not follow British advice should cease to hold their office.

Continuing Great Britain Expands Control of Egypt,

our selection from History of England by James Franck Bright published in 1893. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Great Britain Expands Control of Egypt.

In Egypt itself the protectorate would have been warmly welcomed; and there could be no question as to the impetus which the presence of an English Resident, the representative of the protecting Power, would have imparted to the realization of the contemplated reforms. But the English Government, wisely or unwisely, preferred a far more difficult policy, which appeared to them more consistent with the views they had already declared. They determined to occupy the position of adviser to the Egyptian Government, which should itself carry out a national reform. In a circular addressed to the great Powers in January, 1883, Lord Granville thus explains the policy of his Government: “Although,” he says, “for the present a British force remains in Egypt for the preservation of public tranquility, her Majesty’s Government are desirous of withdrawing it as soon as the state of the country and the organization of proper means for the maintenance of the Khedive’s authority will admit. In the meantime the position in which her Majesty’s Government are placed toward his Highness imposes upon them the duty of giving advice with the object of securing that the order of things to be established shall be satisfactory and shall possess the elements of stability and progress.” Such an attitude has in it something of hollowness. The desire to educate the Egyptians, to raise them till they are fit for self-government, and then to leave them alone is admirable. But advice, to be of value in such circumstances, must be taken. If it is not taken, it must be forced upon the recipient. And this became apparent when exactly a year later Lord Granville wrote to Sir Evelyn Baring, the Consul-General : “It should be made clear to the Egyptian Ministers and Governors of provinces that the responsibility which for a time rests on England obliges her Majesty’s Government to insist on the adoption of the policy which they recommend, and that it will be necessary that those Ministers and Governors who do not follow this course should cease to hold their office.”

Whether the attitude thus assumed was wise or not, the practical work of reconstitution was taken up in earnest. Lord Dufferin was dispatched in November, 1882, to examine the whole situation, and to lay the groundwork of the various necessary reforms. He rapidly removed the obstacles from his way. The Dual Control ceased at the request of the Egyptian Government, and in spite of the opposition of France. The trial of Arabi, which had been a cause of warm dispute between the Egyptian Ministry and England, was brought to a conclusion. The secret and vindictive process by which his countrymen wished to deal with him had been withstood by the English Ministry, who demanded for him at least an open trial. Lord Dufferin arranged a compromise. Arabi, before a court-martial, pleaded guilty of rebellion and was sentenced to death, a sentence immediately commuted by the Khedive into deportation to Ceylon. This act of grace was not performed without a Ministerial crisis; Riaz Pacha and most of the Ministry resigned, but fortunately Cherif continued to hold the Premiership. With his patriotic cooperation the reforms quickly began to assume shape. A financial adviser, Sir Edgar Vincent, was appointed. Steps were taken for the creation of a small Egyptian army under General Evelyn Wood. A native constabulary was raised under General Baker. Mr. Clifford Lloyd, who before long proved too energetic for his place, set to work at the establishment of a police force, and the reform of the prisons and hospitals. Public works were placed under Captain Scott-Moncrieff, who busied himself chiefly with improvements in irrigation; and over the judicial reforms Sir Benson Maxwell was appointed with the title of Procureur-General of the Native Tribunals.

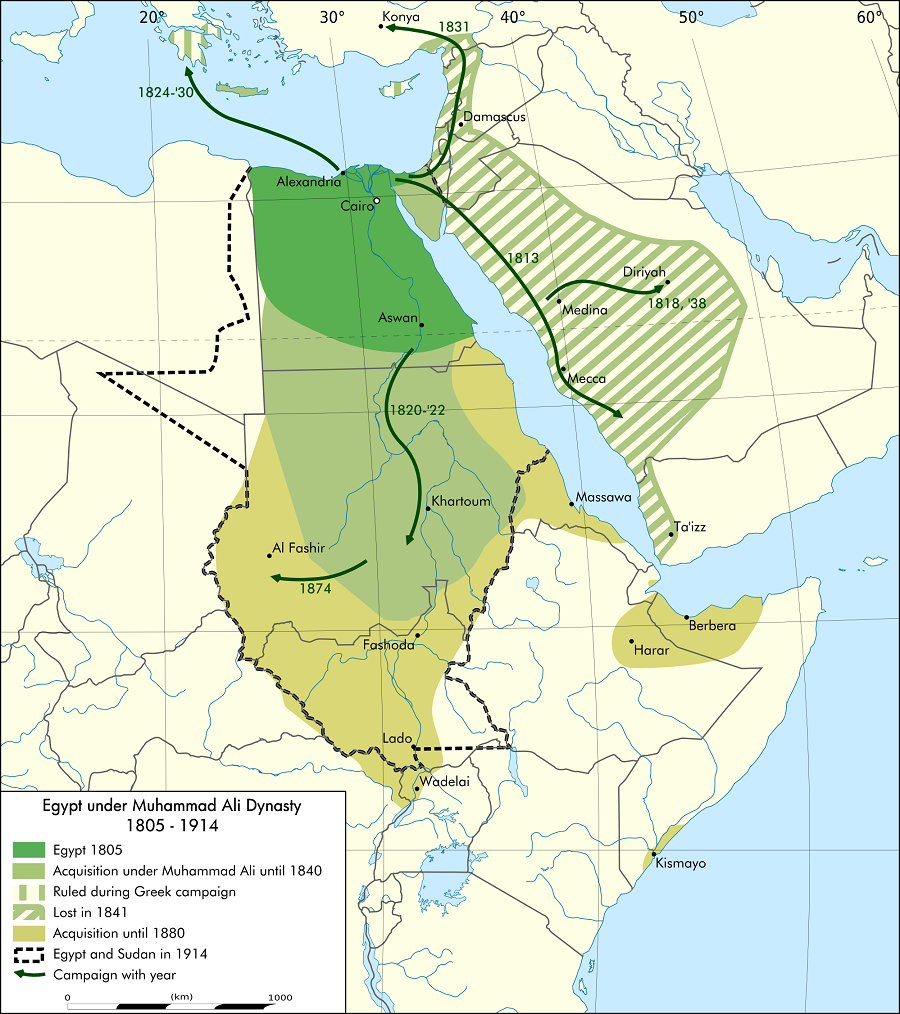

But all these promising reforms were suddenly checked for a time. A fearful epidemic of cholera swept over the country, finding thirty thousand victims; and before the Government had recovered from the paralysis thus caused, the appearance of the Mahdi in the Sudan compelled it to turn all its attention in that direction. It seems that here the real weakness of the position which the English Government had chosen became apparent. For while, by the presence of English troops and the employment of English Ministers and superintendents, the Government at home were obviously charging themselves with the duty of reestablishing Egypt, they positively refused to accept any responsibility with regard to events in the Sudan. While conscious of the inability of Egypt to hold its extended empire, they did not insist on such a diminution of the area of the country and such a con centration of its forces as seemed to be rendered necessary by its diminished power. They allowed the Egyptian army, under Hicks Pacha, to embark on the hopeless project of the reconquest of the Sudan, only to meet with annihilation at the hands of the Mahdi, November 5, 1883. Then, when too late, the pressure of England being at last brought to bear, the Egyptian Ministry under Cherif resigned, Nubar Pacha succeeded to his place, and the evacuation of the Sudan was determined on.

It was an operation of the most extreme difficulty, especially as the English Government clung to its determination of withholding armed assistance from the Egyptians. A man was found whose character and antecedents afforded some hope of his ability to save the situation. General Charles George Gordon (popularly known as “Chinese Gordon”), who had previously ruled Upper Egypt with success, proved willing to undertake the withdrawal of the scattered garrisons whose existence was threatened by the advance of the Mahdi. Trusting to his own unequalled power of influencing half- civilized races, he undertook the duty without the assistance of English troops. There was a distinct understanding, as Lord Hartington declared (April 3rd), that there was to be “no expedition for the relief of Khartum or any garrison in the Sudan.” It was a task beyond his power. All hope of a peaceful conclusion to his mission speedily vanished.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.