This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Nelson Plans the Battle.

Introduction

It was impossible for the powers of Europe to submit quietly to the increasing exactions of the new Emperor, Napoleon, until they had once tried their entire united strength against him in an appeal to arms. What is called the “third great coalition” was formed against France in 1805 by Austria, Russia, and England. Sweden, Naples, and other lesser kingdoms were also partners to it. Spain and several of the little German States aided Napoleon.

The vast plans of the French Emperor included an expedition to cross the Channel and crush England, and to accomplish this he gathered all his available French ships and also those of his ally, Spain. These were intended to protect his army in its passage to England, but Nelson met the French and Spanish fleet off the Spanish coast at Cape Trafalgar, and Britain’s empire over the seas was established beyond doubt.

This selection is from The Life of Horation, Lord Viscount Nelson by Robert Southey published in 1813. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Robert Southey (1774-1843) wrote histories and was one of the writers/poets prominent romantic set in England.

Time: October 21, 1805

Place: Cape Trafalgar, SW coast of Spain

CC BY-SA 2.0 image from Wikipedia.

Nelson arrived off Cadiz on September 29, 1805 -— his birthday. Fearing that if the enemy knew his force they might be deterred from venturing to sea, he kept out of sight of land, desired Collingwood to fire no salute and hoist no colors, and wrote to Gibraltar to request that the force of the fleet might not be inserted there in the Gazette. His reception in the Mediterranean fleet was as gratifying as the farewell of his countrymen at Portsmouth: the officers, who came on board to welcome him, forgot his rank as commander, in their joy at seeing him again. On the day of his arrival Villeneuve received orders to put to sea the first opportunity. Villeneuve, however, hesitated when he heard that Nelson had resumed the command. He called a council of war, and their determination was that it would not be expedient to leave Cadiz, unless they had reason to believe themselves stronger by one-third than the British force. In the public measures of Great Britain secrecy is seldom practicable and seldom attempted: here, however, by the precautions of Nelson and the wise measures of the Admiralty, the French were for once was kept in ignorance; for as the ships appointed to reinforce the Mediterranean fleet were dispatched singly, each as soon as it was ready, their collected number was not stated in the newspapers, and their arrival was not known to the enemy.

On October 9th Nelson sent Collingwood what he called in his diary the “Nelson touch.” “I send you,” said he, “my plan of attack, as far as a man dare venture to guess at the very uncertain position the enemy may be found in; but it is to place you perfectly at ease respecting my intentions, and to give full scope to your judgment for carrying them into effect. We can, my dear Coll, have no little jealousies. We have only one great object in view, that of annihilating our enemies and getting a glorious peace for our country. No man has more confidence in another than I have in you; and no man will render your services more justice than your very old friend, Nelson and Bronte.”

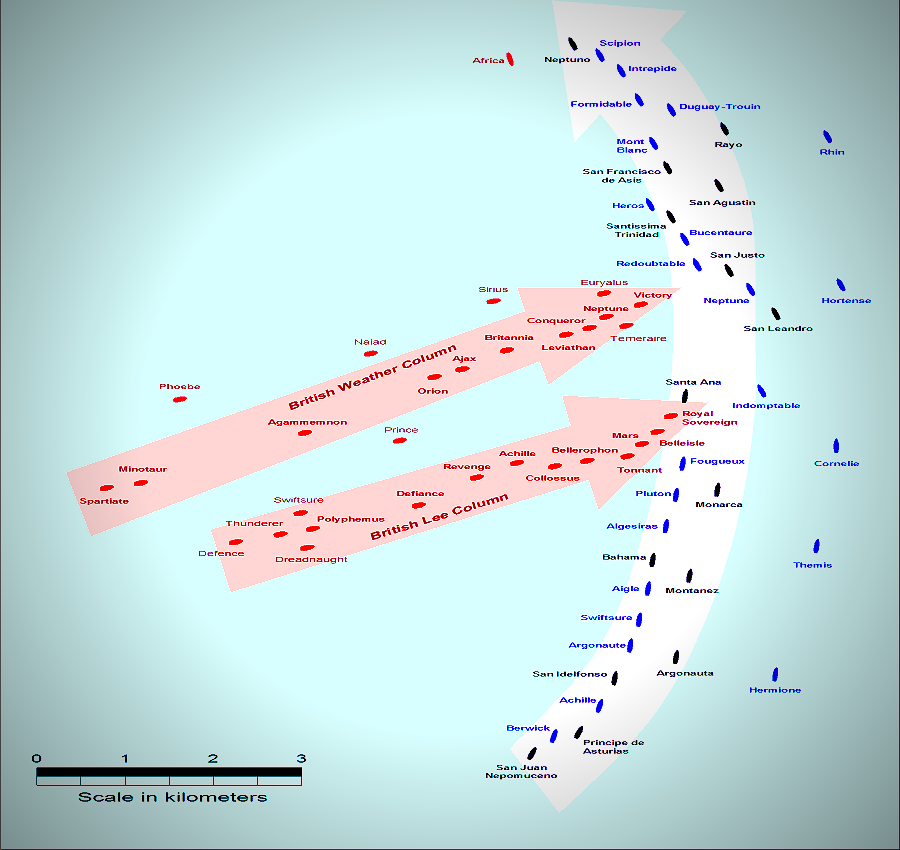

The order of sailing was to be the order of battle; the fleet in two lines, with an advance squadron of eight of the fastest sailing two-deckers. The second in command, having the entire direction of his line, was to break through the enemy, about the twelfth ship from their rear; he would lead through the centre, and the advanced squadron was to cut off three or four ahead of the center. This plan was to be adapted to the strength of the enemy, so that they should always be one-fourth superior to those whom they cut off. Nelson said, “That his admirals and captains, knowing his precise object to be that of a close and decisive action, would supply any deficiency of signals, and act accordingly. In case signals cannot be seen or clearly understood, no captain can do wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.” One of the last orders of this admirable man was that the name and family of every officer, seaman, and marine, who might be killed or wounded in the action, should be, as soon as possible, returned to him in order to be transmitted to the chairman of the patriotic fund, that the case might be taken into consideration for the benefit of the sufferer or his family.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 image from The National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth

On the 21st, at daybreak, the combined fleets were distinctly seen from the Victory’s deck, formed in a close line of battle ahead, on the starboard tack, about twelve miles to leeward, and standing to the south. The English fleet consisted of twenty-seven sail of the line and four frigates; the French, of thirty-three and seven large frigates. The French superiority was more in size and weight of metal than in numbers. They had four thousand troops on board; and the best riflemen who could be procured —- many of them Tyrolese —- were dispersed through the ships. Little did the Tyrolese, and little did the Spaniards, at that day, imagine what horrors the master whom they served was preparing for their countries.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.