This series has two easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Sherman Sets Out.

Introduction

After allowing the Confederate Army to get away when he captured Atlanta, Sherman had to decide what to do next. Hood, the Confederate general side-stepped west and then headed north. Sherman declared, “If Hood wanted to head north I will give him rations. My business is down south.”

This selection is from History of the War of Secession by Rossiter Johnson published in 1868. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Rossiter Johnson (1840-1931) held a doctorate and wrote history books.

Time: 1864

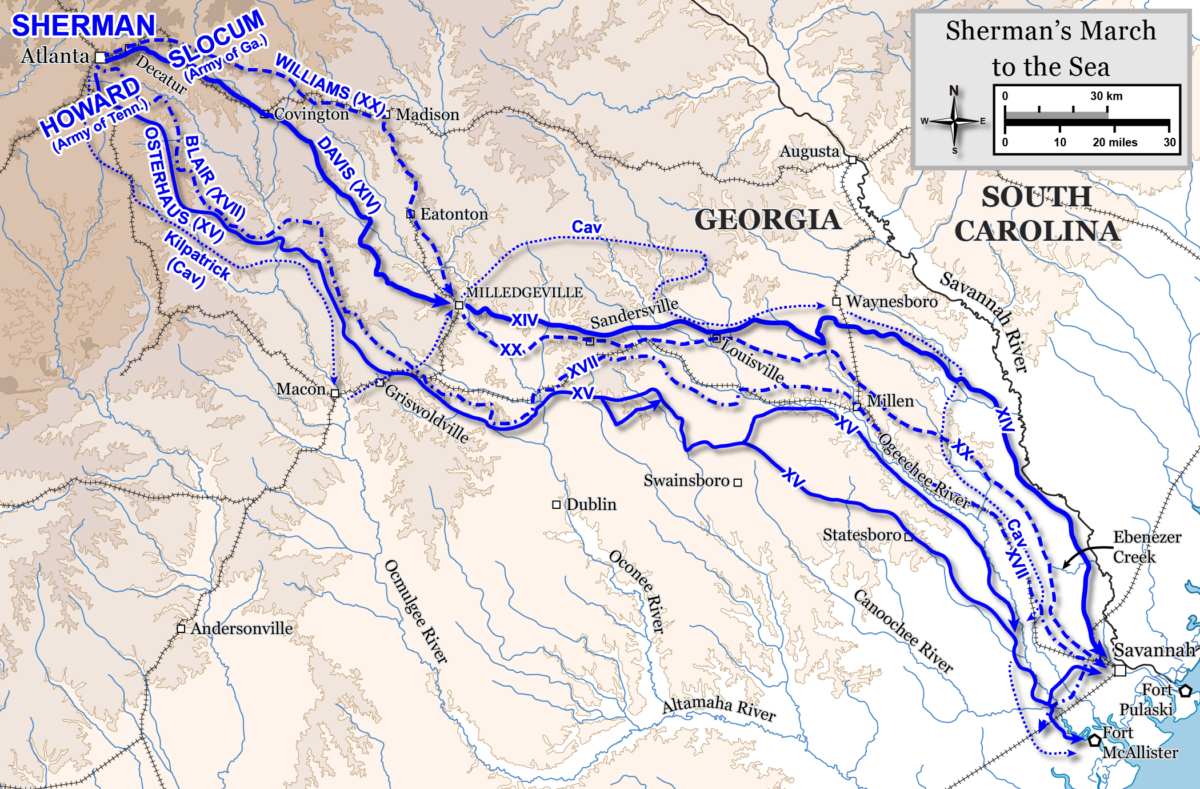

Place: Between Atlanta and Savannah

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

General Sherman thought he conceived of the march to the sea some time in September; the first definite proposal of it was in a telegram to General Thomas on October 9th, in which he said: “I want to destroy all the road below Chattanooga, including Atlanta, and to make for the seacoast. We can not defend this long line of road.” In various dispatches between that date and November 2nd Sherman proposed the great march to Grant and to the President. Grant thought Hood’s army should be destroyed first, but finally said: “I do not see that you can withdraw from where you are, to follow Hood, without giving up all we have gained in territory. I say, then, go on as you propose.” This was on the understanding, suggested by Sherman, that Thomas would be left with force enough to take care of Hood. Sherman sent him the Fourth and Twenty-third Corps, commanded by Generals David S. Stanley and John M. Schofield, and further reinforced him with troops that had been garrisoning various places on the railroad, while he also received two divisions from Missouri and some recruits from the North. These, when properly organized, made up a very strong force; and, with Thomas at its head, neither Sherman nor Grant felt any hesitation about leaving it to take care of Tennessee.

Sherman rapidly sent north all his sick and disabled men, and all baggage that could be spared. Commissioners came and took the votes of the soldiers for the Presidential election, and departed. Paymasters came and paid off the troops, and went back again. Wagon-trains were put in trim and loaded for a march. Every detachment of the army had its exact orders what to do; and as the last trains whirled over the road to Chattanooga, the track was taken up and destroyed, the bridges were burned, the wires torn down, and all the troops that had not been ordered to join Thomas concentrated in Atlanta. From November 12th nothing more was heard from Sherman till Christmas.

The depot, machine-shops, and locomotive-house in Atlanta were torn down, and fire was set to the ruins. The shops had been used for the manufacture of Confederate ammunition, and all night the shells were exploding in the midst of the ruin, while the fire spread to a block of stores, and finally burned out the heart of the city.

With every unsound man and every useless article sent to the rear, General Sherman now had fifty-five thousand three hundred twenty-nine infantrymen, five thousand sixty-three cavalry men, and eighteen hundred twelve artillerymen, with sixty five guns. There were four teams of horses to each gun, with its caisson and forge; six hundred ambulances, each drawn by two horses; and twenty-five hundred wagons, with six mules to each. Every soldier carried forty rounds of ammunition, while the wagons contained an abundant additional supply and twelve hundred thousand rations, with oats and corn enough to last five days. Probably a more thoroughly appointed army never was seen, and it is difficult to imagine one of equal numbers more effective. Every man in it was a veteran, was proud to be there, and felt the most perfect confidence that under the leadership of “Uncle Billy ” it would be impossible to go wrong.

On November 15th they set out on the march to the sea, nearly three hundred miles distant. The infantry consisted of four corps. The Fifteenth and Seventeenth formed the right wing, commanded by General Oliver O. Howard; the Fourteenth and Twentieth the left, commanded by General Henry W. Slocum. The cavalry was under the command of General Judson Kilpatrick. The two wings marched by parallel routes, usually a few miles apart, each corps having its own proportion of the artillery and trains. General Sherman issued minute orders as to the conduct of the march, which were systematically carried out. Some of the instructions were these:

The habitual order of march will be, wherever practicable, by four roads, as nearly parallel as possible. The separate columns will start habitually at 7 A.M., and make about fifteen miles a day. Behind each regiment should follow one wagon and one ambulance. Army commanders should practice the habit of giving the artillery and wagons the road, marching the troops on one side. The army will forage liberally on the country during the march. To this end each brigade commander will organize a good and sufficient foraging party, who will gather corn or forage of any kind, meat of any kind, vegetables, corn meal, or whatever is needed by the command, aiming at all times to keep in the wagons at least ten days’ provisions. Soldiers must not enter dwellings or commit any trespass; but, during a halt or camp, they may be permitted to gather turnips, potatoes, and other vegetables, and to drive in stock in sight of their camp. To corps commanders alone is entrusted the power to destroy mills, houses, cotton-gins, etc. Where the army is unmolested, no destruction of such property should be permitted; but should guerillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less relentless, according to the measure of such hostility. As for horses, mules, wagons, etc., belonging to the inhabitants, the cavalry and artillery may appropriate freely and without limit; discriminating, however, between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor and industrious, usually neutral or friendly. In foraging, the parties engaged will endeavor to leave with each family a reasonable portion for their maintenance.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.