Today’s installment concludes The Battle of Trafalgar,

our selection from The Life of Horation, Lord Viscount Nelson by Robert Southey published in 1813.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Battle of Trafalgar.

Time: October 21, 1805

Place: Cape Trafalgar, SW coast of Spain

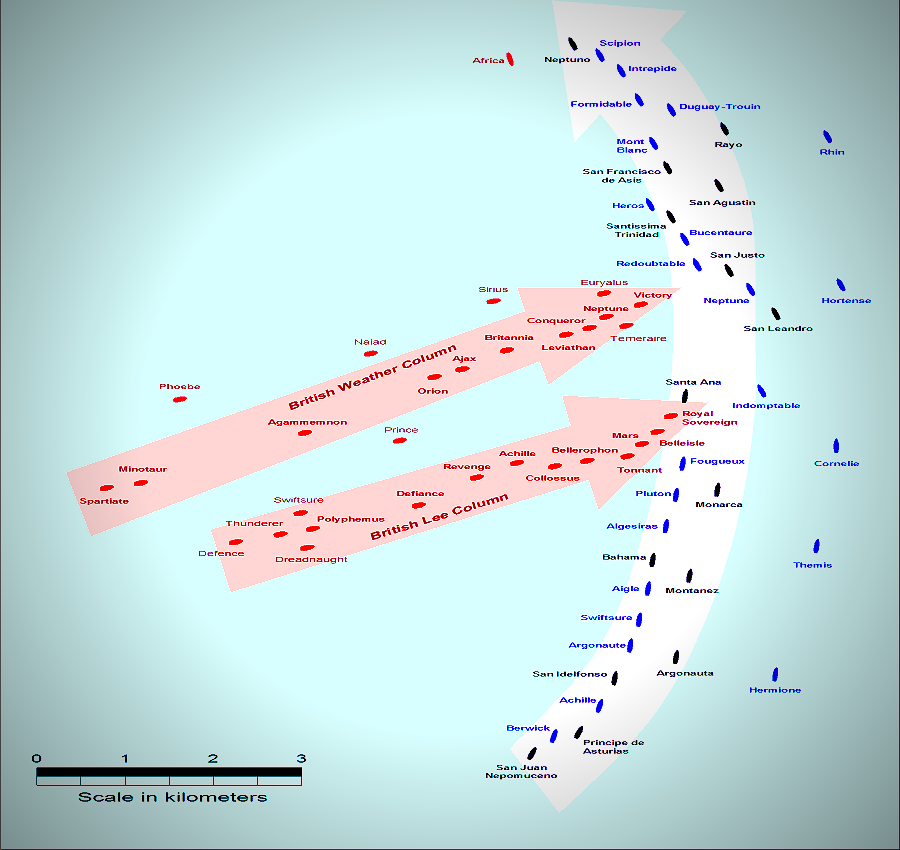

CC BY-SA 2.0 image from Wikipedia.

Yet even now, not for a moment losing his presence of mind, Nelson observed, as they were carrying him down the ladder, that the tiller-ropes, which had been shot away, were not yet replaced, and ordered that new ones should be rove immediately: then, that he might not be seen by the crew, he took out his handkerchief and covered his face and his stars. Had he but concealed these badges of honor from the enemy, England perhaps would not have had cause to receive with sorrow the news of the Battle of Trafalgar. The cockpit was crowded with wounded and dying men, over whose bodies he was with some difficulty conveyed and laid upon a pallet in the midshipmen’s berth.

It was soon perceived, upon examination, that the wound was mortal. This, however, was concealed from all except Captain Hardy, the chaplain, and the medical attendants. He himself being certain, from the sensation in his back, and the gush of blood he felt momentarily within his breast, that no human care could avail him, insisted that the surgeon should leave him and attend to those to whom he might be useful. “For,” said he, “you can do nothing for me.” All that could be done was to fan him with paper, and frequently to give him lemonade to alleviate his intense thirst. He was in great pain and expressed much anxiety for the event of the action, which now began to declare itself. As often as a ship struck, the crew of the Victory hurrahed; and at every hurrah a visible expression of joy gleamed in the eye and marked the countenance of the dying hero. But he became impatient to see Captain Hardy; and as that officer, though often sent for, could not leave the deck, Nelson feared that some fatal cause prevented him, and repeatedly cried: “Will no one bring Hardy to me? He must be killed! He is surely dead!” An hour and ten minutes elapsed from the time when Nelson received his wound before Hardy could come to him. They shook hands in silence: Hardy in vain struggling to suppress the feelings of that most painful and yet sublimest moment. “Well, Hardy,” said Nelson, “how goes the day with us ?” “Very well,” replied Hardy; “ten ships have struck, but five of the van have tacked, and show an intention to bear down upon the Victory. I have called two or three of our fresh ships round and have no doubt of giving them a drubbing.” “I hope,” said Nelson, “none of our ships have struck?” Hardy answered, “There is no fear of that.” Then, and not till then, Nelson spoke of himself. “I am a dead man, Hardy,” said he; “I am going fast; it will be all over with me soon. Come nearer to me. Let my dear Lady Hamilton have my hair and all other things belonging to me.” Hardy observed that he hoped Mr. Beatty could yet hold out some prospect of life. “Oh, no!” he replied, “it is impossible: my back is shot through; Beatty will tell you so.” Captain Hardy then once more shook hands with him, and, with a heart almost bursting, hastened upon deck.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 image from The National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth

By this time all feeling below the breast was gone; and Nelson, having made the surgeon ascertain this, said to him: “You know I am gone. I know it. I feel something rising in my breast” —- putting his hand on his left side —- “which tells me so.” And on Beatty’s inquiring whether his pain was great, he said it was so great that he wished he was dead. “Yet,” said he in a lower voice, “one would like to live a little longer, too.” And after a few minutes, in the same undertone, he added, “What would become of poor Lady Hamilton if she knew my situation?” Next to his country she occupied his thoughts. Captain Hardy, some fifty minutes after he left the cockpit, returned, and again taking the hand of his dying friend and commander, congratulated him on having gained a complete victory. How many of the enemy were taken he did not know, as it was impossible to perceive them distinctly; but fourteen or fifteen at least. “That’s we,” cried Nelson, “but I bargained for twenty.” And then, in a stronger voice, he said, “Anchor, Hardy, anchor!” Hardy, upon this, hinted that Admiral Collingwood would take upon himself the direction of affairs. “Not while I live, Hardy,” said the dying Nelson, ineffectually endeavoring to raise himself from the bed: “Do you anchor!” His previous order for preparing to anchor had shown how clearly he foresaw the necessity of this. Presently, calling Hardy back, he said to him in a low voice, “Don’t throw me overboard”; and he desired that he might be buried by his parents, unless it should please the King to order otherwise. Then reverting to private feelings: “Take care of my dear Lady Hamilton, Hardy; take care of poor Lady Hamilton. Kiss me, Hardy,” said he. Hardy knelt down and kissed his cheek, and Nelson said: “Now I am satisfied. Thank God, I have done my duty.” Hardy stood over him in silence for a moment or two, then knelt again and kissed his forehead. “Who is that?” said Nelson; and being informed, he replied, “God bless you, Hardy.” And Hardy then left him —- forever.

Nelson now desired to be turned upon his right side, and said, “I wish I had not left the deck; for I shall soon be gone.” Death was, indeed, rapidly approaching. He said to the chaplain, “Doctor, I have not been a great sinner, ”and after a short pause, “Remember that I leave Lady Hamilton and my daughter Horatia as a legacy to my country.” His articulation now became difficult; but he was distinctly heard to say, “Thank God, I have done my duty!” These words he repeatedly pronounced; and they were the last words which he uttered. He expired at thirty minutes after four —- three hours and a quarter after he had received his wound.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Battle of Trafalgar by Robert Southey from his book The Life of Horation, Lord Viscount Nelson published in 1813. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Battle of Trafalgar here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.