Today’s installment concludes Leipzig Battle of the Nations,

our selection from History of Germany by Wolfgang Menzel published in 1852.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Leipzig Battle of the Nations.

Time: 1813

Place: Leipzig, Saxony

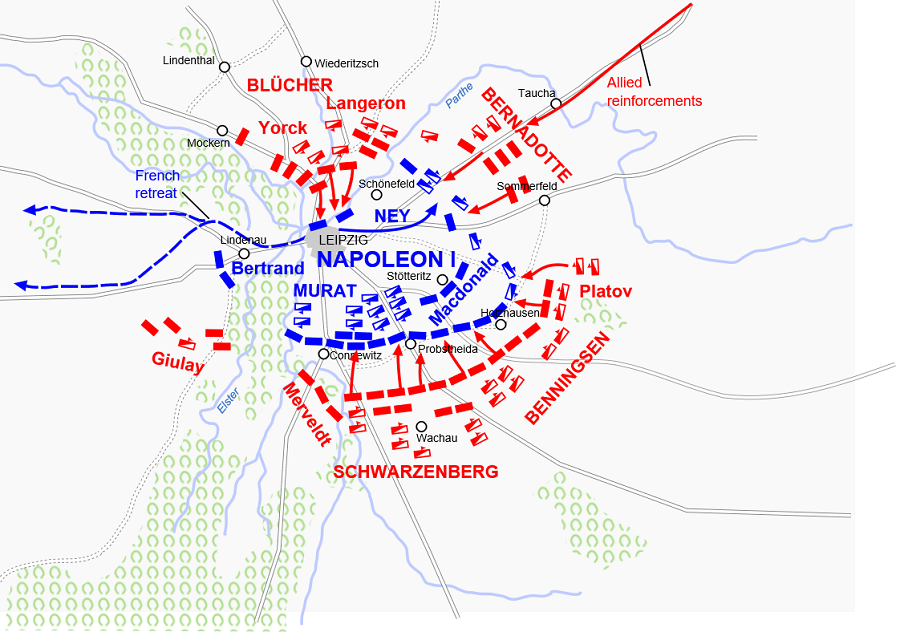

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The battle had, on October r6th, raged around Leipsic; Napoleon had triumphed over the Austrians, whom he had solely intended to attack, but had, at the same time, been attacked and defeated by the Prussians, and now found himself opposed and almost surrounded by the whole allied force—one road for retreat alone remaining open. He instantly gave orders to General Bertrand to occupy Weissenfels during the night, in order to secure his retreat through Thuringia; but, during the following day, October 17th, he neither seized that opportunity to retreat nor to make a last attack upon the allies — whose forces were not yet completely concentrated — ere the circle had been fully drawn around him. The Swedes, the Russians under Bennigsen, and a large Austrian division under Colloredo had not yet arrived.

Napoleon might with advantage have again attacked the defeated Austrians under Schwarzenberg or have thrown himself with the whole of his forces upon Blucher. He had still an opportunity of making an orderly retreat without any great exposure to danger. But he did neither. He remained motionless during the whole day, which was also passed in tranquility by the allies, who thus gained time to receive fresh reinforcements. Napoleon’s inactivity was caused by his having sent his prisoner, General Meerveldt, to the Emperor of Austria, whom he still hoped to induce, by means of great assurances, to secede from the coalition and to make peace. Not even a reply was vouch-safed. On the very day, thus futilely lost by Napoleon, the allied army was reintegrated by the arrival of the masses commanded by the Crown Prince, by Bennigsen and Colloredo, and was consequently raised to double the strength of that of France, which now merely amounted to one hundred fifty thousand men.

On the 18th a murderous conflict began on both sides. Napoleon long and skillfully opposed the fierce onset of the allied troops, but was at length driven off the field by their superior weight and persevering efforts. The Austrians, stationed on the left wing of the allied army, were opposed by Oudinot, Augereau, and Poniatowsky; the Prussians, stationed on the right wing, by Mammont and Ney; the Russians and Swedes in the center, by Murat and Regnier. In the hottest of the battle two Saxon cavalry regiments went over to Blucher, and General Normann, when about to be charged at Taucha by the Prussian cavalry under Buelow, also deserted to him with two Wurtemberg cavalry regiments, in order to avoid an unpleasant reminiscence of the treacherous ill-treatment of Luetzow’s corps. The whole of the Saxon infantry, commanded by Regnier, shortly afterward went, with thirty-eight guns, over to the Swedes, five hundred men and General Zeschau alone remaining true to Napoleon. The Saxons stationed themselves behind the lines of the allies, but their guns were instantly turned upon the enemy.

In the evening of this terrible day the French were driven back close upon the walls of Leipzig. * On the certainty of victory being announced by Schwarzenberg to the three monarchs, who had watched the progress of the battle, they knelt on the open field and returned thanks to God. Napoleon, before night fall, gave orders for full retreat; but, on the morning of the 19th, recommenced the battle and sacrificed some of his corps d’armée in order to save the remainder. He had, however, foolishly left but one bridge across the Elster open, and the retreat was consequently retarded. Leipzig was stormed by the Prussians, and, while the French rear-guard was still battling on that side of the bridge, Napoleon fled and had no sooner crossed the bridge than it was blown up with a tremendous explosion, owing to the inadvertence of a subaltern, who is said to have fired the train too hastily.

[* The city was in a state of utter confusion. The noise caused by the passage of the cavalry, carriages, etc., and by the cries of the fugitives through the streets exceeded that of the most terrific storm. The earth shook, the windows clattered with the thunder of artillery.]

The troops engaged on the opposite bank were irremediably lost. Prince Poniatowsky plunged on horseback into the Elster in order to swim across but sank in the deep mud. The King of Saxony, who to the last had remained true to Napoleon, was among the prisoners. The loss during this battle, which raged for four days and in which almost every nation in Europe stood opposed to each other, was immense on both sides. The total loss in dead was computed at eighty thousand. The French lost, moreover, three hundred guns and a multitude of prisoners — in the city of Leipzig alone twenty-three thousand sick, without reckoning the innumerable wounded. Numbers of these unfortunates lay bleeding and starving to death during the cold October nights on the field of battle, it being found impossible to erect a sufficient number of lazarelti for their accommodation.

Napoleon made a hasty and disorderly retreat with the remainder of his troops, but was overtaken at Freiburg on the Unstrut, where the bridge broke and a repetition of the disastrous passage of the Beresina occurred. The fugitives collected into a dense mass, upon which the Prussian artillery played with murderous effect. The French lost forty of their guns. At Hanan, Wrede, Napoleon’s former favorite, after taking Wuerzburg, watched the movements of his ancient patron, and, had he occupied the pass at Gelnhausen, might have annihilated him. Napoleon, however, furiously charged his flank, and, on October 20th, succeeded in forcing a passage and in sending seventy thousand men across the Rhine.

Wrede was dangerously wounded. On November 9th the last French corps was defeated at Hochheim and driven back upon Mainz. In the November of this ever memorable year, 1813, Germany, as far as the Rhine, was completely freed from the French.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Leipzig Battle of the Nations by Wolfgang Menzel from his book History of Germany published in 1852. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Leipzig Battle of the Nations here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.