In August, 1813, the tempest of war broke loose on every side, and all Europe prepared for a decisive struggle.

Continuing Leipzig Battle of the Nations,

our selection from History of Germany by Wolfgang Menzel published in 1852. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Leipzig Battle of the Nations.

Time: 1813

Place: Leipzig, Saxony

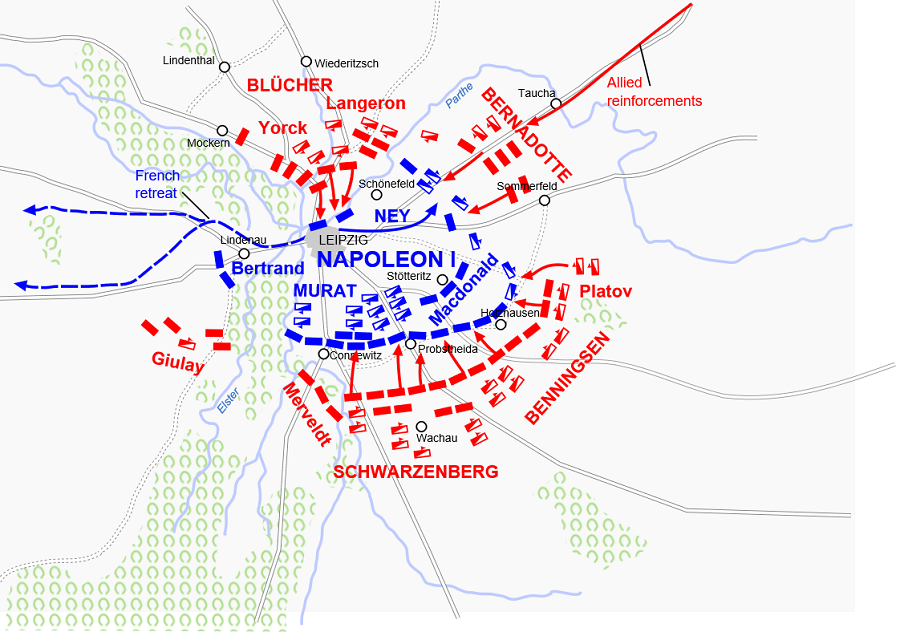

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Napoleon had concentrated his main body, that still consisted of two hundred fifty thousand men, in and around Dresden. Davoust received orders to advance with thirty thousand men from Hamburg upon Berlin; in Bavaria, there were thirty thou sand men under Wrede; in Italy, forty thousand under Eugene. The German fortresses were, moreover, strongly garrisoned with French troops. Napoleon took up a defensive position with his main body at Dresden, whence he could watch the proceedings and take advantage of any indiscretion on the part of his opponents. A body of ninety thousand men under Oudinot meantime acted on the offensive, being directed to advance, simultaneously with Davoust from Hamburg and with Girard from Magdeburg, upon Berlin, and to take possession of that metropolis. Napoleon hoped, when master of the ancient Prussian provinces, to be able to suppress German enthusiasm at its source, and to induce Russia and Austria to conclude a separate peace at the expense of Prussia.

In August, 1813, the tempest of war broke loose on every side, and all Europe prepared for a decisive struggle. About this time, the whole of Northern Germany was visited for some weeks, as was the case on the defeat of Varus in the Teutoburg forest, with heavy rains and violent storms. The elements seemed to combine their efforts, as in Russia, with those of man against Napoleon. There his soldiers fell victims to frost and snow, here they sank into the boggy soil and were carried away by the swollen rivers. In the midst of the uproar of the elements, bloody engagements continually took place, in which the bayonet and the butt end of the firelock were used, the muskets being rendered unserviceable by the water.

The first engagement of importance was that of August 21st between Wallmoden and Davoust at Vellahn. A few days later, Karl Theodor Koerner, the youthful poet and hero, fell in a skirmish between the French and Wallmoden’s outpost at Gadobusch. Oudinot advanced close upon Berlin, which was protected by the Crown Prince of Sweden. A murderous conflict took place, on August 23d, at Grossbeeren between the Prussian division under General von Buelow and the French. The Swedes, a troop of horse artillery alone excepted, were not brought into action, and the Prussians, unaided, repulsed the greatly superior forces of the French. The almost untrained peasantry comprising the landwehr of the Mark and of Pomerania rushed upon the enemy, and, unaccustomed to the use of the bayonet and firelock, beat down entire battalions of the French with the butt end of their muskets. After a frightful massacre, the French were utterly routed and fled in wild disorder, but the gallant Prussians vainly expected the Swedes to aid in the pursuit. The Crown Prince, partly from a desire to spare his troops and partly from a feeling of shame —— he was also a Frenchman — remained motionless. Oudinot, nevertheless, lost two thousand four hundred, taken prisoner. Davoust, from this disaster, returned once more to Hamburg. Girard, who had advanced with eight thousand men from Magdeburg, was, on the 27th, put to flight by the Prussian landwehr under General Hirschfeld.

Napoleon’s plan of attack against Prussia had completely failed, and his sole alternative was to act on the defensive. But on perceiving that the main body of the allied forces under Schwarzenberg was advancing to his rear, while Blucher was stationed with merely a weak division in Silesia, he took the field with immensely superior forces against the latter, under an idea of being able easily to vanquish his weak antagonist and to fall back again in time upon Dresden. Blucher cautiously retired, but, unable to restrain the martial spirit of the soldiery, who obstinately defended every position whence they were driven, lost two thousand of his men on August 21st.

Napoleon had pursued Blucher as far as the Katzbach near Goldberg, when he returned and boldly resolved to cross the Elbe above Dresden, to seize the passes of the Bohemian mountains, and to fall upon the rear of the main body of the allied army. Vandamme’s corps d’arme’e had already set forward with this design, when Napoleon learned that Dresden could no longer hold out unless he returned thither with a division of his army, and, in order to preserve that city and the center of his position, he hastily returned thither in the hope of defeating the allied army and of bringing it between two fires, as Vandamme must meanwhile have occupied the narrow outlets of the Erzgebirge with thirty thousand men and by that means cut off the retreat of the allied army.

The plan was on a grand scale, and, as far as related to Napoleon in person, was executed, to the extreme discomfiture of the allies, with his usual success. Schwarzenberg, with true Austrian procrastination, had allowed August 2 5th to pass in inaction, when, as the French themselves confess, Dresden, in her then ill-defended state, might have been taken almost without a stroke. When he attempted to storm the city on the 26th, Napoleon, who had meanwhile arrived, calmly awaited the onset of the thick masses of the enemy in order to open a murderous discharge of grape upon them on every side. They were repulsed after suffering a frightful loss. On the following day, destined to end in still more terrible bloodshed, Napoleon assumed the offensive, separated the retiring allied army by well-combined sallies, cut off its left wing, and made an immense number of prisoners, chiefly Austrians. The unfortunate Moreau had both his legs shot off in the very first encounter. His death was an act of jus tice, for he had taken up arms against his fellow-countrymen.

The main body of the allied army retreated on every side; part of the troops disbanded, the rest were exposed to extreme hardship owing to the torrents of rain that fell without intermission, and the scarcity of provisions. Their annihilation must have inevitably followed had Vandamme executed Napoleon’s commands and blocked up the mountain passes, in which he was unsuccessful, being defeated and, with his whole division, taken prisoner near Culm (August 29, 1813).

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.