This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Napoleon’s Choices in Germany .

Introduction

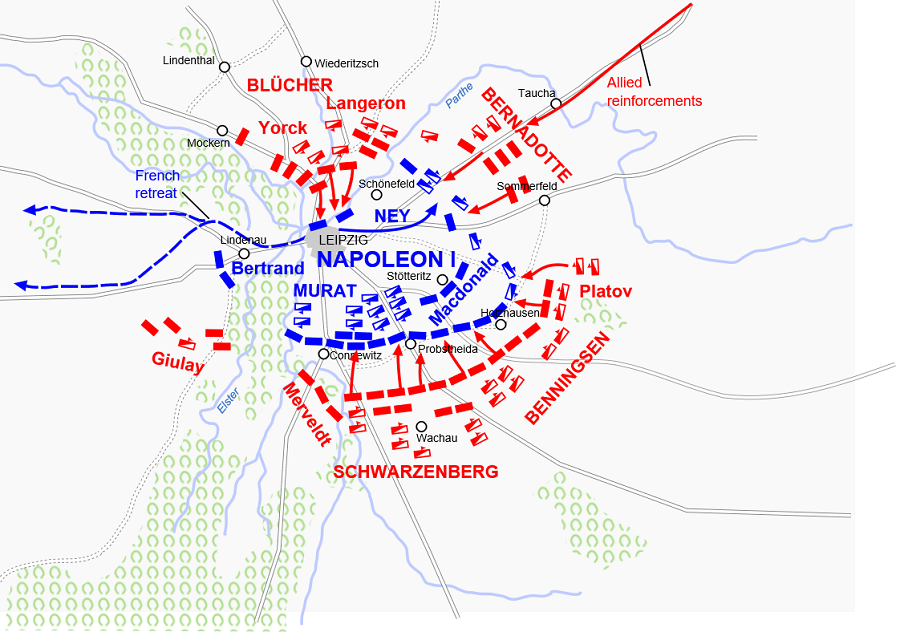

After the debacle in Russia the previous year, Napoleon faced a revival of the coalition against him. The countries that he had defeated – Prussia, Austria, the smaller sovereignties in Germany and further afield – now rose up again. The campaign in Germany climaxed in the great Battle of the Nations outside of Leipzig.

This selection is from History of Germany by Wolfgang Menzel published in 1852. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Wolfgang Menzel (1798-1873) was historian of Germany’s past.

Time: 1813

Place: Leipzig, Saxony

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The King of Prussia had suddenly abandoned Berlin, which was still in the hands of the French, for Breslau, whence he declared war against France. A conference also took place between him and Emperor Alexander at Kalisch, and, on February 28, 1813, an offensive and defensive alliance was concluded between them. The hour for vengeance had at length arrived. The whole Prussian nation, eager to throw off the hated yoke of the foreigner, to obliterate their disgrace in 1806, to regain their ancient name, cheerfully hastened to place their lives and property at the service of the impoverished Government. The whole of the able-bodied population was put under arms. The standing army was increased: to each regiment were appended troops of volunteers, jaegers, composed of young men belonging to the higher classes, who furnished their own equipments. A numerous landwehr, a sort of militia, was, as in Austria, raised besides the standing army, and measures were even taken to call out, in case of necessity, the heads of families and elderly men remaining at home, under the name of the “landsturm”. [1]

[1: Literally, the general levy of the people. — Ed.]

When news of these preparations reached Davoust he sent serious warning to Napoleon, who contemptuously replied, “Pah! Germans never can become Spaniards!” With his customary rapidity he levied in France a fresh army three hundred thousand strong, with which he so completely awed the Rhenish Confederation as to compel it to take the field once more with thousands of Germans against their brother-Germans. The troops, however, obeyed reluctantly, and even the traitors were but luke-warm, for they doubted of success. Mecklenburg alone sided with Prussia. Austria remained neutral.

A Russian corps under General Tettenborn had preceded the rest of the troops and reached the coasts of the Baltic. As early as March 24, 1813, it appeared in Hamburg and expelled the French authorities from the city. The heavily oppressed people of Hamburg, whose commerce had been totally annihilated by the Continental System, gave way to the utmost demonstrations of delight, received their deliverers with open arms, revived their ancient rights, and immediately raised a Hanseatic corps, destined to take the field against Napoleon. As the army advanced, Baron von Stein was nominated chief of the Provisional Government of the still unconquered provinces of Western Germany.

Wittgenstein, pushed forward to Magdeburg, and, at Moeckern, repulsed forty thousand French, who were advancing upon Berlin. The Prussians, under their veteran general, Blucher, entered Saxony and garrisoned Dresden, on March 27, 1813; an arch of the fine bridge across the Elbe having been uselessly blown up by the French. Blucher, whose gallantry in the former wars had gained for him the general esteem, and whose kind and generous disposition had won the affection of the soldiery, was nominated generalissimo of the Prussian forces, but subordinate in command to Wittgenstein, who replaced Kutusoff (w) as generalissimo of the united forces of Russia and Prussia. The Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia accompanied the army and were received with loud acclamations by the people of Dresden and Leipzig. The allied army was merely seventy thousand strong, and Blueher had not formed a junction with Wittgenstein when Napoleon invaded the country by Erfurt and Merseburg at the head of one hundred sixty thousand men.

[2: Kutusoff had recently died.-ED.]

On the eve of the bloody engagement of May 2d the allied cavalry attempted a general attack in the dark, which was unsuccessful on account of the superiority of the enemy’s forces. The allies had, nevertheless, captured some cannon; the French, none. The most painful loss was that of the noble Schamhorst, who was mortally wounded. Buelow had, on the same day, stormed Halle with a Prussian corps, but was now compelled to resolve upon a retreat, which was conducted in the most orderly manner by the allies. At Koldiz the Prussian rear guard repulsed the French van in a bloody engagement on May 5th.

Napoleon attacked the allies at Bautzen from May 19th to the 21st, but was gloriously repulsed by the Prussians under Kleist, while Blucher, who was in danger of being completely surrounded, undauntedly defended himself on three sides. The French had suffered an immense loss; eighteen thousand of their wounded were sent to Dresden. Napoleon’s favorite, Marshal Duroc and General Kirchner, a native of Alsace, were killed, close to his side, by a cannon-ball. The allied troops, forced to retire after an obstinate encounter, neither fled nor dispersed, but withdrew in close column and repelling each successive attack. The whole of the lowlands of Silesia now lay open to the French, who entered Breslau on June 1st.

Napoleon remained at Breslau awaiting the arrival of reinforcements, and to rest his unseasoned troops, mostly conscripts. In the meantime he demanded an armistice, to which the allies, whose force was still incomplete and to whom the decision of Austria was of equal importance, gladly assented. On this celebrated armistice, concluded June 4, 1813, at the village of Pleisswitz, the fate of Europe was to depend. Napoleon’s power was still terrible; fresh victory had obliterated the disgrace of his flight from Russia; he stood once more an invincible leader on German soil. The French were animated by success and blindly devoted to their Emperor. Italy and Denmark were prostrate at his feet. The Rhenish Confederation was also faithful to his standard. The declaration of the Emperor of Austria in favor of his son-in-law, Napoleon, who was lavish of promises, and, among other things, offered to restore Silesia, was consequently, at the opening of the armistice, deemed certain.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.