This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Grant Receives a Message From Lee.

Introduction

When the main Confederate army, led by Robert E. Lee, abandoned the defensive works in front of Petersburg, near Richmond, the campaign of 1865 began. It was in the nature of a chase. Lee’s army tried to get away to join the other large Confederate army in North Carolina; Grant’s army tried to catch him. Grant succeeded and that’s where this story begins.

This selection is from Memoirs of Grant by Ulysses S. Grant published in 1885. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) wrote his memoirs and as you can read for yourself, it is a classic of the genre.

Time: April 8, 1865

Place: Neighborhood of Assomatox Court House, Virginia

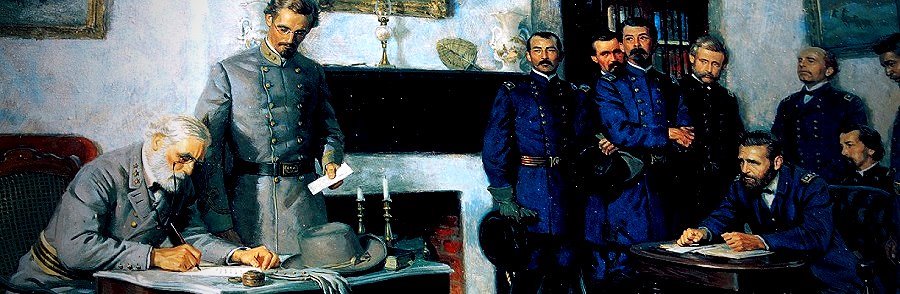

Fair use image

On April 8th [1865] I had followed the Army of the Potomac in rear of Lee. I was suffering very severely with a sick headache and stopped at a farmhouse on the road, some distance in rear of the main body of the army. I spent the night in bathing my feet in hot water and mustard, and putting mustard plasters on my wrists and the back part of my neck, hoping to be cured by morning. During the night I received Lee’s answer to my letter of the 8th, inviting an interview between the lines on the following morning. But it was for a different purpose from that of surrendering his army, and I answered him as follows:

HEADQUARTERS

ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES, April 9, 1865.

GENERAL R. E. LEE, Commanding Confederate States Armies:

“Your note of yesterday is received. I have no authority to treat on the subject of peace; the meeting proposed for 10 A.M. to-day could lead to no good. I will state, however, General, that I am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertains the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Sincerely hoping that all our difficulties may be settled without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself, etc.,

U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.”

I proceeded at an early hour in the morning, still suffering with the headache, to get to the head of the column. I was not more than two or three miles from Appomattox Court House at the time; but to go direct I would have to pass through Lee’s army or a portion of it. I had therefore to move south in order to get upon a road coming up from another direction.

When the white flag was put out by Lee, as already described, I was in this way moving toward Appomattox Court House, and consequently could not be communicated with immediately and be informed of what Lee had done. Lee, therefore, sent a flag to the rear to advise Meade, and one to the front to Sheridan, saying that he had sent a message to me for the purpose of having a meeting to consult about the surrender of his army, and asked for a suspension of hostilities until I could be communicated with. As they had heard nothing of this until the fighting had got to be severe and all going against Lee, both of these commanders hesitated very considerably about suspending hostilities at all. They were afraid it was not in good faith, and we had the Army of Northern Virginia where it could not escape except by some deception. They, however, finally consented to a suspension of hostilities for two hours, to give an opportunity of communicating with me in that time, if possible. It was found that, from the route I had taken, they would probably not be able to communicate with me and get an answer back within the time fixed unless the messenger should pass through the Confederate lines. Lee, therefore, sent an escort with the officer bearing this message through his lines to me:

April 9, 1865. “GENERAL:

I received your note of this morning on the picket line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday, with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask an interview, in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday, for that purpose.

R. E. LEE, General.

Lieutenant-General U. S. GRANT, Commanding United States Armies.”

When the officer reached me I was still suffering with the sick headache but the instant I saw the contents of the note I was cured. I wrote the following note in reply and hastened on:

April 9, 1865.

GENERAL R. E. LEE, Commanding Confederate States Armies:

Your note of this date is but this moment (11.50 A.M.) received, in consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and Lynchburg road to the Farmville and Lynchburg road. I am at this writing about four miles west of Walker’s Church, and will push forward to the front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent to me on this road where you wish the interview to take place will meet me.

U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.”

I was conducted at once to where Sheridan was located with his troops drawn up in line of battle facing the Confederate army nearby. They were very much excited and expressed their view that this was all a ruse employed to enable the Confederates to get away. They said they believed that Johnston was marching up from North Carolina now, and Lee was moving to join him; and they would whip the rebels where they now were in five minutes if I would only let them go in. But I had no doubt about the good faith of Lee, and pretty soon was conducted to where he was. I found him at the house of a Mr. McLean, at Appomattox Court House, with Colonel Marshall, one of his staff-officers, awaiting my arrival. The head of his column was occupying a hill, on a portion of which was an apple-orchard, beyond a little valley which separated it from that on the crest of which Sheridan’s forces were drawn up in line of battle to the south.

Before stating what took place between General Lee and myself, I will give all there is of the story of the famous apple-tree. Wars produce many stories of fiction, some of which are told until they are believed to be true. The War of the Rebellion was no exception to this rule and the story of the apple-tree is one of those fictions based on a slight foundation of fact. As I have said, there was an apple-orchard on the side of the hill occupied by the Confederate forces. Running diagonally up the hill was a wagon-road, which at one point ran very near one of the trees, so that the wheels of vehicles had on that side cut off the roots of this tree, leaving a little embankment. General Babcock, of my staff, reported to me that when he first met General Lee he was sitting upon this embankment with his feet in the road below and his back resting against the tree. The story had no other foundation than that. Like many other stories, it would be very good if it were only true.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.