Today’s installment concludes Lee Surrenders at Appomatox,

our selection from Memoirs of Grant by Ulysses S. Grant published in 1885.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lee Surrenders at Appomatox.

Time: April 9, 1865

Place: Assomatox Court House, Virginia

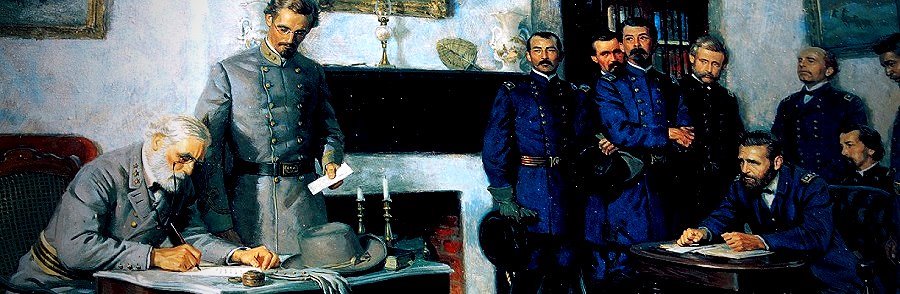

Fair use image

I then said to him that I thought this would be about the last battle of the war. I sincerely hoped so; and I said, further, I took it that most of the men in the ranks were small farmers. The whole country had been so raided by the two armies that it was doubtful whether they would be able to put in a crop to carry themselves and their families through the next winter without the aid of the horses they were then riding. The United States did not want them, and I would therefore instruct the officers I left behind to receive the paroles of his troops to let every man of the Confederate army who claimed to own a horse or mule take the animal to his home. Lee remarked again that this would have a happy effect. He then sat down and wrote out the fol lowing letter:

HEADQUARTERS

“ARMY or NORTHERN VIRGINIA, April 9, 1865.

“GENERAL: I have received your letter of this date containing the terms of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia as proposed by you. As they are substantially the same as those expressed in your letter of the 8th instant, they are accepted. I will proceed to designate the proper officers to carry the stipulations into effect.

R. E. LEE, General.

“Lieutenant-General U. S. GRANT.”

While duplicates of the two letters were being made, the Union Generals present were severally presented to General Lee.

The much-talked-of surrendering of Lee’s sword and my handing it back — this and much more that has been said about it — is the purest romance. The word “sword” or “side-arms” was not mentioned by either of us until I wrote it in the terms. There was no premeditation and it did not occur to me until the moment I wrote it down. If I had happened to omit it and General Lee had called my attention to it, I should have put it in the terms precisely as I acceded to the provision about the soldiers retaining their horses.

General Lee, after all was completed, and before taking his leave, remarked that his army was in a very bad condition for want of food and that they were without forage; that his men had been living for some days on parched corn exclusively and that he would have to ask me for rations and forage. I told him, “Certainly,” and asked for how many men he wanted rations. His answer was, “About twenty-five thousand”; and I authorized him to send his own commissary and quartermaster to Appomattox Station, two or three miles away, where he could have, out of the trains we had stopped, all the provisions wanted. As for forage, we had ourselves depended almost entirely upon the country for that.

Generals Gibbon, Griffin, and Merritt were designated by me to carry into effect the paroling of Lee’s troops before they should start for their homes — General Lee leaving Generals Longstreet, Gordon, and Pendleton for them to confer with in order to facilitate this work. Lee and I then separated as cordially as we had met, he returning to his own lines and all went into bivouac for the night at Appomattox.

Soon after Lee’s departure I telegraphed to Washington as follows:

HEADQUARTERS,

“APPOMATTOX COURT HOUSE, VA.,

“April 9, 1865, 4.30 P.M.

“HON. E. M. STANTON, Secretary of War, Washington:

“General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia this afternoon on terms proposed by myself. The accompanying additional correspondence will show the conditions fully.

“U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.”

When news of the surrender first reached our lines our men commenced firing a salute of a hundred guns in honor of the victory. I at once sent word, however, to have it stopped. The Confederates were now our prisoners, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.

I determined to return to Washington at once, with a view to putting a stop to the purchase of supplies and what I now deemed other useless outlay of money. Before leaving, however, I thought I would like to see General Lee again; so next morning I rode out beyond our lines toward his headquarters, preceded by a bugler and a staff-officer carrying a white flag.

Lee soon mounted his horse, seeing who it was, and met me. We had there between the lines, sitting on horseback, a very pleasant conversation of over half an hour, in the course of which Lee said to me that the South was a big country, and that we might have to march over it three or four times before the war entirely ended, but that we would now be able to do it, as they could no longer resist us. He expressed it as his earnest hope, however, that we would not be called upon to cause more loss and sacrifice of life; but he could not foretell the result. I then suggested to General Lee that there was not a man in the Confederacy whose influence with the soldiery and the whole people was as great as his; and that if he would now advise the surrender of all the armies I had no doubt his advice would be followed with alacrity. But Lee said he could not do that without consulting the President first. I knew there was no use to urge him to do anything against his ideas of what was right.

I was accompanied by my staff and other officers, some of whom seemed to have a great desire to go inside the Confederate lines. They finally asked permission of Lee to do so for the purpose of seeing some of their old army friends, and the permission was granted. They went over, had a very pleasant time with their old friends, and brought some of them back with them when they returned.

When Lee and I separated he went back to his lines and I returned to the house of Mr. McLean. Here the officers of both armies came in great numbers and seemed to enjoy the meeting as much as if they had been friends separated for a long time while fighting battles under the same flag. For the time being, it looked very much as if all thought of the war had escaped their minds. After an hour pleasantly passed in this way, I set out on horseback, accompanied by my staff and a small escort, for Burkesville Junction, up to which point the railroad had by this time been repaired.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Lee Surrenders at Appomatox by Ulysses S. Grant from his book Memoirs of Grant published in 1885. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Lee Surrenders at Appomatox here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.