Austria, at first, instead of aiding the allies, allowed the Poles to range themselves beneath the standard of Napoleon, whom she overwhelmed with protestations of friendship.

Continuing Leipzig Battle of the Nations,

our selection from History of Germany by Wolfgang Menzel published in 1852. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Leipzig Battle of the Nations.

Time: 1813

Place: Leipzig, Saxony

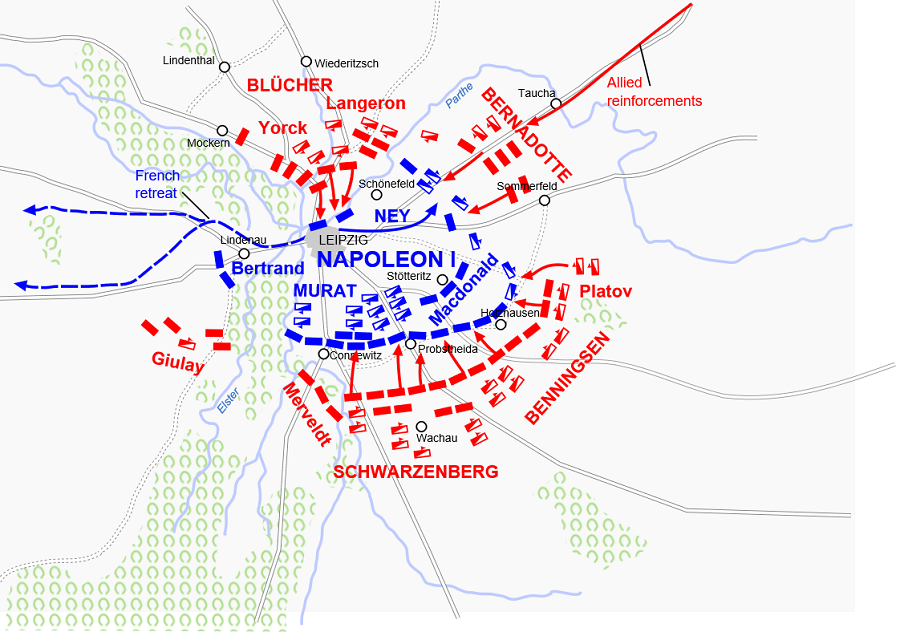

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Austria, at first, instead of aiding the allies, allowed the Poles to range themselves beneath the standard of Napoleon, whom she overwhelmed with protestations of friendship, which served to mask her real intentions, and meanwhile gave her time to arm herself to the teeth and to make the allies sensible of the fact of their utter impotency against Napoleon unless aided by her. The interests of Austria favored her alliance with France, but Napoleon, instead of confidence, inspired mistrust. Austria, notwithstanding the marriage between him and Maria Louisa, was, as had been shown at the Congress of Dresden, treated merely as a tributary to France, and Napoleon’s ambition offered no guarantee to the ancient imperial dynasty. There was no security that the provinces bestowed in momentary reward for her alliance must not, on the first occasion, be restored. Nor was public opinion entirely without weight. Napoleon’s star was on the wane, whole nations stood like to a dark and ominous cloud threatening on the horizon, and Count Metternich prudently chose rather to attempt to guide the storm ere it burst than trust to a falling star.

Austria had, as early as June 27, 1813, signed a treaty, at Reichenbach in Silesia, with Russia and Prussia, by which she bound herself to declare war against France in case Napoleon had not before July 20th accepted the terms of peace about to be proposed to him. Already the sovereigns and generals of Rus sia and Prussia had sketched — during a conference held with the Crown Prince of Sweden, July 11th, at Trachenberg — the plan for the approaching campaign, and, with the permission of Austria, assigned to her the part she was to take as one of the allies against Napoleon, when Count Metternich visited Dresden, in person, for the purpose of repeating his assurances of amity — for the armistice had but just commenced — to Napoleon.

The French Emperor had an indistinct idea of the transactions then passing, and bluntly said to the Count, “As you wish to mediate, you are no longer on my side.” He hoped partly to win Austria over by redoubling his promises, partly to terrify her by the dread of the future ascendency of Russia but, perceiving how Metternich evaded him by his artful diplomacy, he suddenly asked, “Well, Metternich, how much has England given you in order to engage you to play this part toward me ?” This trait of insolence toward an antagonist of whose superiority he felt conscious, and of the most deadly hatred masked by contempt, was peculiarly characteristic of the Corsican, who, besides the qualities of the lion, fully possessed those of the cat. Napoleon let his hat drop in order to see whether Metternich would raise it. He did not, and war was resolved upon.

A pretended congress for the conclusion of peace was again arranged by both sides; by Napoleon, in order to elude the reproach cast upon him of an insurmountable and eternal desire for war, and by the allies, in order to prove to the whole world their desire for peace. Each side was, however, fully aware that the palm of peace was alone to be found on the other side of the battlefield. Napoleon was generous in his concessions but delayed granting full powers to his envoy, an opportune circum stance for the allies, who were by this means able to charge him with the whole blame of procrastination. Napoleon, in all his concessions, merely included Russia and Austria to the exclusion of Prussia.

But neither Russia nor Austria trusted to his promises, and the negotiations were broken off on the termination of the armistice, when Napoleon sent full powers to his plenipotentiary. Now, it was said, it is too late! The art with which Metternich passed from the alliance with Napoleon to neutrality, to mediation, and finally to the coalition against him, will, in every age, be acknowledged a masterpiece of diplomacy. Austria, while coalescing with Russia and Prussia, in a certain degree assumed a rank conventionally superior to both. The whole of the allied armies was placed under the command of an Austrian general, Prince von Schwarzenberg and if the proclamation published at Kalisch had merely summoned the people of Germany to assert their independence, the manifesto of Count Metternich spoke already in the tone of the future regulator of the affairs of Europe.

Austria declared herself on August 12, 1813, two days after the termination of the armistice.

Immediately after this — for all had been previously arranged — the monarchs of Russia and Prussia passed the Riesengebirge with a division of their forces into Bohemia, and joined the Emperor Francis and the great Austrian army at Prague. The celebrated general, Moreau, who had returned from America, where he had hitherto dwelt incognito, in order to take up arms against Napoleon, was in the train of the Czar. His example, it was hoped, would induce many of his countrymen to abandon Napoleon.

The plan of the allies was to advance with their main body, under Schwarzenberg, consisting of one hundred twenty thousand Austrians and seventy thousand Russians and Prussians, through the Erzgebirge to Napoleon’s rear. A lesser Prussian force, principally Silesian landwehr, under Blucher, eighty thousand strong, besides a small Russian corps, was meanwhile to cover Silesia, or, in case of an attack by Napoleon’s main body, to retire before it and draw it farther eastward. A third division, under the Crown Prince of Sweden, principally Swedes, with some Prussian troops, mostly Pomeranian and Brandenburg landwehr under Buelow, and some Russians, in all ninety thou sand men, was destined to cover Berlin, and in case of a victory to form a junction in Napoleon’s rear with the main body of the allied army. A still lesser and equally mixed division under Wallmoden, thirty thousand strong, was destined to watch Davoust in Hamburg, while an Austrian corps of twenty-five thousand men under Prince Reuss watched the movements of the Bavarians, and another Austrian force of forty thousand, under Hiller, those of the Viceroy, Eugene, in Italy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.