Napoleon’s generals had been thrown back in every quarter, with immense loss, upon Dresden, toward which the allies now advanced.

Continuing Leipzig Battle of the Nations,

our selection from History of Germany by Wolfgang Menzel published in 1852. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Leipzig Battle of the Nations.

Time: 1813

Place: Leipzig, Saxony

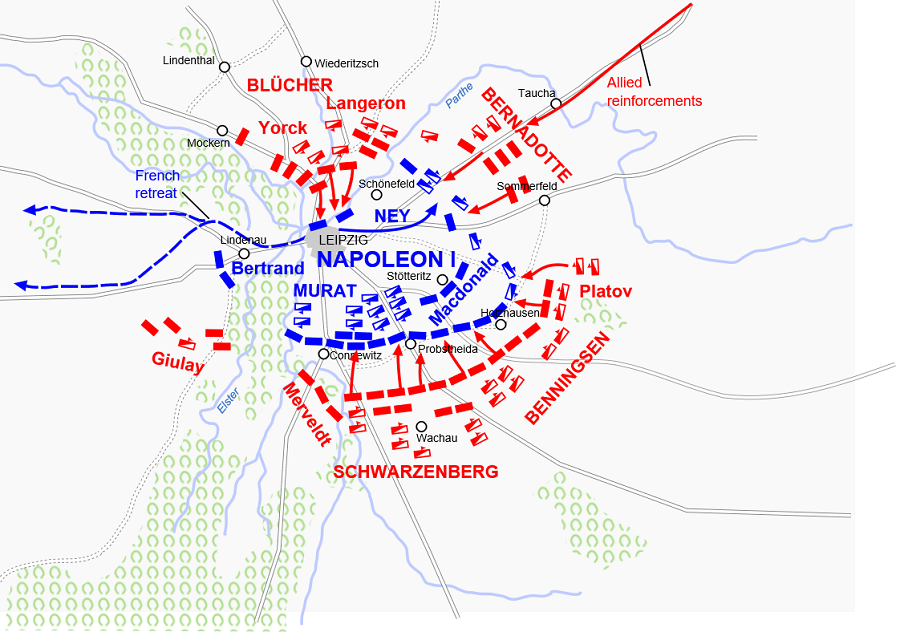

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On August 26th a signal victory was gained by Blucher in Silesia. After having drawn Macdonald across the Katzbach and the foaming Neisse, he drove him, after a desperate and bloody engagement, into those rivers, which were greatly swollen by the incessant rains. The muskets of the soldiery had been rendered unserviceable by the wet, and Blucher, drawing his sabre from beneath his cloak, dashed forward exclaiming, “Forward!” Several thousand of the French were drowned or fell by the bayonet, or beneath the heavy blows dealt by the landwehr with the butt ends of their firelocks. Blucher was rewarded with the title of Prince von der Wahlstadt, but his soldiers surnamed him Marshal “Vorwaerts” (Forward). The French lost one hundred three guns, eighteen thousand prisoners, and a still greater number in killed; the loss on the side of the Prussians amounted to one thousand men. Macdonald returned almost totally unattended to Dresden and brought the melancholy intelligence to Napoleon.

The Crown Prince of Sweden and Buelow had meanwhile pursued Oudinot’s retreating corps in the direction of the Elbe. Napoleon dispatched Ney against them, but he met with the fate of his predecessor, at Dennewitz, on September 6th. The Prussians, on this occasion, again triumphed, unaided by their confederates. Buelow and Tauenzien, with twenty thousand men, defeated the French army, seventy thousand strong. The French lost eighteen thousand men and eighty guns. The rout was complete. The rear-guard, consisting of the Wurtembergers under Franquemont, was again overtaken at the head of the bridge at Zwittau, and, after a frightful carnage, driven in wild confusion across the dam to Torgau.

Napoleon’s generals had been thrown back in every quarter, with immense loss, upon Dresden, toward which the allies now advanced, threatening to enclose it on every side. Napoleon maneuvered until the beginning of October with the view of executing a coup de main against Schwarzenberg and Blucher; the allies were, however, on their guard, and he was constantly reduced to the necessity of recalling his troops, sent for that purpose into the field, to Dresden. The danger in which he now stood of being completely surrounded and cut off from the Rhine at length rendered retreat his sole alternative. Blucher had already crossed the Elbe on October 5th, and, in conjunction with the Crown Prince of Sweden, had approached the head of the main body of the allied army under Schwarzenberg, which was advancing from the Erzgebirge.

On October 7th Napoleon quitted Dresden, leaving a garrison of thirty thousand French under St. Cyr, and removed his headquarters to Duben, on the road leading from Leipzig to Belin, in the hope of drawing Blucher and the Swedes once more on the right side of the Elbe, in which case he intended to turn unexpectedly upon the Austrians; Blucher, however, eluded him, without quitting the left bank. Napoleon’s plan was to take advantage of the absence of Blucher and of the Swedes from Berlin in order to hasten across the defenseless country, for the purpose of inflicting punishment upon Prussia, of raising Poland, etc. But his plan met with opposition in his own military council. His ill success had caused those who had hitherto followed his fortunes to waver. The King of Bavaria declared against him on October 8th, and the Bavarian army under Wrede united with, instead of opposing, the Austrian army, and was sent to the Maine in order to cut off Napoleon’s retreat. The news of this defection speedily reached the French camp and caused the rest of the troops of the Rhenish Confederation to waver in their allegiance; while the French, wearied with useless maneuvers, beaten in every quarter, opposed by an enemy greatly their superior in number and glowing with revenge, despaired of the event and sighed for peace and their quiet homes. All refused to march upon Berlin, nay, the very idea of removing farther from Paris almost produced a mutiny in the camp.

Four days, from October 11th to the 14th, were passed by Napoleon in a state of melancholy irresolution, when he appeared as if suddenly inspired by the idea of there still being time to execute a coup de main upon the main body of the allied army under Schwarzenberg before its junction with Blucher and the Swedes. Schwarzenberg was slowly advancing from Bohemia and had already allowed himself to be defeated before Dresden. Napoleon intended to fall upon him on his arrival in the vicinity of Leipzig but it was already too late — Blucher was at hand. On October 14th * the flower of the French cavalry, headed by the King of Naples, encountered Blucher’s and Wittgenstein’s cavalry at Wachau, not far from Leipzig. The contest was broken off, both sides being desirous of husbanding their strength, but terminated to the disadvantage of the French notwithstanding their numerical superiority, besides proving the vicinity of the Prussians. This was the most important cavalry fight that took place during this war.

[* On the evening of October 14th (the anniversary of the Battle of Jena) a hurricane raged in the neighborhood of Leipsic, where the French lay, carrying away roofs and uprooting trees, while, during the whole night, the rain fell in torrents.]

On October 16th, while Napoleon was merely awaiting the arrival of Macdonald’s corps, that had remained behind, before proceeding to attack Schwarzenberg’s Bohemian army, he was unexpectedly attacked on the right bank of the Pleisse, at Liebertwolkwitz, by the Austrians, who were, however, compelled to retire before a superior force. The French cavalry under Latour-Mauborg pressed so closely upon the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia that they merely owed their escape to the gallantry of the Russian, Orloff Denisoff, and to Latour’s fall. Napoleon had already ordered all the bells in Leipzig to be rumg, had sent the news of his victory to Paris, and seems to have expected a complete triumph when joyfully exclaiming, “Le monde toume pour nous!” (“ The world [everything] changes for us! ”)

But his victory had been only partial, and he had been unable to follow up his advantage, another division of the Austrian army, under General Meerveldt, having simultaneously occupied him and compelled him to cross the Pleisse at Dolnitz; and, although Meerveldt had been in his turn repulsed with severe loss and been himself taken prisoner, the diversion proved of service to the Austrians by keeping Napoleon in check until the arrival of Blucher, who threw himself upon the division of the French army opposed to him at Moeckern by Marshal Marmont. Napoleon, while thus occupied with the Austrians, was unable to meet the attack of the Prussians with sufficient force. Mammont, after a massacre of some hours’ duration in and around Moeckern, was compelled to retire with the loss of forty guns. The second Prussian brigade lost, either in killed or wounded, all its officers except one.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.