They had little whereupon to feast, except a miserable compound of wheat and barley boiled with water, and even to the larger portion of this the worms successfully laid claim.

Continuing English Settle Virginia,

our selection from A History of Virginia by Robert Reid Howison published in 1846. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English Settle Virginia.

Time: 1607

Place: Jamestown

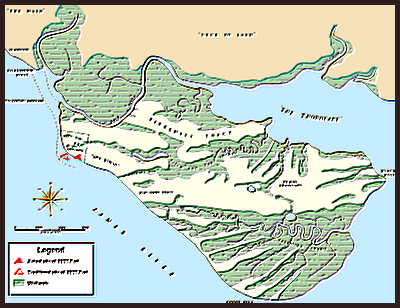

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

His talent for command excited the mean jealousy of inferior souls, only that his merit might appear brighter by contrast. If we have aught to urge against him, it is that he met the treachery of the Indians with a severe spirit, but too much akin to that of the Spaniards in the South. Yet we cannot reproach him with undeserved cruelty or with deliberate falsehood, and the stern demands of his circumstances often rendered inevitable acts which would otherwise have been ungrateful to his soul.

When the council was constituted, Edward Maria Wingfield was elected president — a man who always proved an inveterate enemy to Smith, and who speedily attracted the hatred even of his accomplices by his rapacity, his cowardice, and his selfish extravagance. Smith demanded a trial, but the council feared to trust their wretched charge to an impartial jury, and pretended, in mercy to him, to keep him under suspension. But their own incompetence soon brought his talents into demand. He accompanied Newport upon an exploring voyage up the river, and ascended to the residence of King Powhatan, a few miles below the falls, and not far from the spot now occupied by the city of Richmond. The royal seat consisted of twelve small houses, pleasantly placed on the north bank of the river, and immediately in front of three verdant islets. His Indian majesty received them with becoming hospitality, though his profound dissimulation corresponded but too well with the treacherous designs of his followers. He had long ruled with sovereign sway among the most powerful tribes of Virginia, who had been successively subdued by his arms, and he now regarded with distrust the event of men whom his experience taught him to fear and his injuries to detest.

On their return to Jamestown they found that, during their absence, the Indians had made an attack upon the settlement, had slain one boy, and wounded seventeen men. The coward spirit of Wingfield had caused this disaster. Fearful of mutiny he refused to permit the fort to be palisaded or guns to be mounted within. The assault of the savages might have been more fatal, but happily a gun from the ships carried a crossbar-shot among the boughs of a tree above them, and, shaking them down upon their heads, produced great consternation. The frightened wretches fled in dismay from an attack too mysterious to be solved, yet too terrible to be withstood.

After this disaster the fears of Wingfield were overruled — the fort was defended by palisades, and armed with heavy ordnance, the men were exercised, and every precaution was used to guard against a sudden attack or a treacherous ambuscade.

Smith had indignantly rejected every offer held out to him by the artifices of the council. He now again demanded a trial in a manner that could not be resisted. The examination took place and resulted in his full acquittal. So evident was the injustice of the president that he was adjudged to pay to the accused two hundred pounds, which sum the generous Smith immediately devoted to the store of the colony. Thus elevated to his merited place in the council, he immediately devised and commenced active schemes for the welfare of the settlers, and on June 15th Newport left the colony, and set forth on his voyage of return to England.

Left to their own resources, the colonists began to look with gloomy apprehension upon the prospect before them. While the ships remained, they enjoyed sea-stores, which to them were real luxuries, but now they had little whereupon to feast, except a miserable compound of wheat and barley boiled with water, and even to the larger portion of this the worms successfully laid claim. Crabs and oysters were sought with indolent greediness, and this unwholesome fare, with the increasing heats of the season, produced sickness, which preyed rapidly on their strength. The rank vegetation of the country pleased the eye, but it was fatal to the health. In ten days hardly ten settlers were able to stand. Before the month of September fifty of their number were committed to the grave, and among them we mark, with sorrow, the name of Bartholomew Gosnold. The gallant seaman might have passed many years upon the stormy coasts of the continent, but he sank among the first victims who risked their lives for colonization.

To this scene of distress and appalling mortality the president Wingfield lived in sumptuous indifference. His gluttony appropriated to itself the best provisions the colony could afford — “oatmeal, sacke, oyle, aqua vitae, beefe, egges, or whatnot” — and, in this intemperate feasting, it seemed as though his valueless life were only spared that he might endure the disgrace he so richly merited. Seeing the forlorn condition of the settlement he attempted to seize the pinnace, which had been left for their use by Newport, and make his escape to England. These outrages so wrought upon the council that they instantly deposed him, expelled his accomplice, Kendall, and elected Ratcliffe to the presidency. Thus their body, consisting originally of seven, was reduced to three. Newport had sailed, Gosnold was dead, Wingfield and Kendall were in disgraced seclusion. Martin, Ratcliffe, and Smith alone remained. They seem to have felt no desire to exercise their right of filling their vacant ranks. The first had a nominal superiority, but the genius of the last made him the very soul of the settlement.

It is related by the best authority that in this dark crisis, when their counsels were distracted, their hopes nearly extinguished, their bodies enfeebled from famine and disease, the savages around them voluntarily brought in such quantities of venison, corn, and wholesome fruits that health and cheerfulness were at once restored. Their condition now brought them in almost daily contact with the aborigines.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.