We will not now pause to consider it minutely either for praise or for blame.

Continuing English Settle Virginia,

our selection from A History of Virginia by Robert Reid Howison published in 1846. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English Settle Virginia.

Time: 1606

Place: London

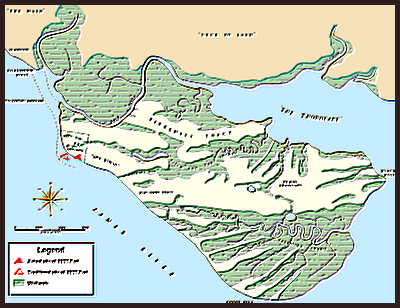

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But how shall these colonial subjects be governed? — and from whom shall they derive their laws? These were questions to which the vanity and the arbitrary principles of the King soon found a reply. Two councils were to be provided, one for each colony, and each consisting of thirteen members. They were to govern the colonists according to such laws, ordinances, and instructions as should afterward be given by the King himself, under his sign manual and the privy seal of the realm of England; and the members of the council were to be “ordained, made, and removed from time to time,” as the same instructions should direct. In addition to these provincial bodies a council of thirteen, likewise appointed by the King, was to be created in England, to which was committed the general duty of superintending the affairs of both colonies.

And to prove the pious designs of a monarch whose religion neither checked the bigotry of his spirit nor the profaneness of his language it was recited in the preamble of this charter that one leading object of the enterprise was the propagation of Christianity among “such people as yet live in darkness and miserable ignorance of the true knowledge and worship of God, and might in time be brought to human civility and to a settled and quiet government.”

Such was the first charter of James to the colony of Virginia. We will not now pause to consider it minutely either for praise or for blame. With some provisions that seem to be judicious, and which afterward proved themselves to be salutary, it embraces the most destructive elements of despotism and dissension. The settlers were deprived of the meanest privilege of self-government, and were subjected to the control of a council wholly independent of their own action, and of laws proceeding directly or indirectly from the King himself. The Parliament of England would have been a much safer depositary of legislative power for the colonists than the creatures of a monarch who held doctrines worthy of the Sultan of Turkey or the Czar of the Russian empire.

But all parties seemed well satisfied with this charter, and neither the King nor the adventurers had before their minds the grand results that were now giving birth. The patentees diligently urged forward preparations for the voyage, and James employed his leisure hours in preparing the instructions and code of laws contemplated by the charter. His wondrous wisdom rejoiced in the task of acting the modern Solon, and penning statutes which were to govern the people yet unborn; and neither his advisers nor the colonists seemed to have reflected upon the enormous exercise of prerogative herein displayed. The adventurers did not cease to be Englishmen in becoming settlers of a foreign clime, and the charter had expressly guaranteed to them “all liberties, franchises, and immunities” enjoyed by native-born subjects of the realm. Even acts of full Parliament bind not the colonies unless they be expressly included, and an English writer of subsequent times has not hesitated to pronounce this conduct of the royal law-maker in itself illegal (November 20th). But James proceeded with much eagerness to a task grateful alike to his vanity and his principles of government.

By these articles of instruction, the King first establishes the general council, to remain in England, for the superintendence of the colonies. It consisted originally of thirteen, but was afterward increased to nearly forty, and a distinction was made in reference to the London and Plymouth companies. In this body we note many names which were afterward well known both in the interests of America and the mother-land.

Sir William Wade, lieutenant of the Tower of London; Sir Thomas Smith, Sir Oliver Cromwell, Sir Herbert Croft, Sir Edwin Sandys, and others formed a power to whom were entrusted many of the rights of the intended settlement. They were authorized, at the pleasure and in the name of his majesty, to give directions for the good government of the settlers in Virginia, and to appoint the first members of the councils to be resident in the colonies.

These resident councils thus appointed, or the major part of them, were required to choose from their own body a member, not being a minister of God’s Word, who was to be president, and to continue in office for a single year. They were authorized to fill vacancies in their own body, and, for sufficient cause, to remove the president and elect another in his stead; but the authority to “increase, alter, or change” these provincial councils was reserved as a final right to the King.

The Church of England was at once established, and the local powers were to require that the true word and service of God, according to her teachings, should be preached, planted, and used, not only among the settlers, but, as far as possible, among the sons of the forest.

The crimes of the rebellion, tumults, conspiracy, mutiny, and sedition, as well as murder, incest, rape, and adultery, were to be punished with death, without benefit of clergy. To manslaughter, clergy was allowed. These crimes were to be tried by jury, but the president and council were to preside at the trial — to pass sentence of death — to permit no reprieve without their order, and no absolute pardon without the sanction of the King, under the great seal of England.

But with the exception of these capital felonies, the president and council were authorized to hear and determine all crimes and misdemeanors, and all civil cases, without the intervention of a jury. These judicial proceedings were to be summary and verbal, and the judgment only was to be briefly registered in a book kept for the purpose.

For five years succeeding the landing of the settlers, all the results of their labor were to be held in common, and were to be stored in suitable magazines. The president and the council were to elect a “cape merchant” to superintend these public houses of deposit, and two clerks to note all that went into or came out from them, and every colonist was to be supplied from the magazines by the direction and appointment of these officers or of the council.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.