This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: James I Grants Patents for Virginia Colonization.

Introduction

More than a century went by since Spain and Portugal began settling the western hemisphere and England basically did nothing about it. So far as England was concerned, the lands across the ocean might as well have been another planet. But when the country did finally decide to begin settling, their settlements really took off.

This selection is from A History of Virginia by Robert Reid Howison published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Robert Reid Howison (1820-1906) was an early Virginia historian.

Time: April 10, 1606

Place: London

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On April 10, 1606, James I issued a patent to Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Somers, Richard Hakluyt, and others with them associated, under which they proposed to embark upon their eagerly sought scheme. This royal grant deserves our close attention, as it will explain the nature of the enterprise and the powers originally enjoyed by those who entered upon it.

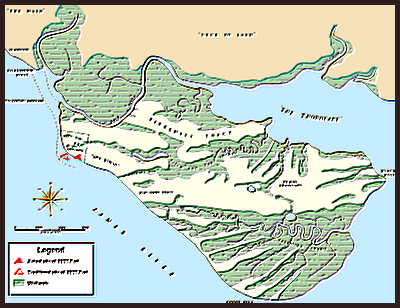

Selecting for the scene of operations the beautiful belt of country lying between the thirty-fourth and forty-fifth parallels of north latitude, the King certainly provided an ample field for the success of the patentees. This tract extends from Cape Fear to Halifax, and embraces all the lands between its boundaries in North America, except perhaps the French settlement in Arcadia, which had already been so far matured as to come under the excluding clause of the patent. For colonizing this extensive region the King appointed two companies of adventurers — the first consisting of noblemen, knights, gentlemen, and others in and about the city of London, which, through all its subsequent modifications, was known by the title of the London Company; the other consisted of knights, gentlemen, merchants, and others in and about the town of Plymouth, and was known as the Plymouth Company, though its operations were never extensive and were at last utterly fruitless.

To the London adventurers was granted exclusive right to all the territory lying between the thirty-fourth and thirty-eighth parallels and running from the ocean to an indefinite extent westward into the wilds of America, even to the waters of the Pacific. They were also allowed all the islands, fisheries, and other marine treasures within one hundred miles directly eastward from their shores and within fifty miles from their most northern and most southern settlements, following the coast to the northeast or southwest, as might be necessary. Within these limits ample jurisdiction was conferred upon them. To the Plymouth Company were granted in like manner the land and appurtenances between the forty-first and forty-fifth parallels. Thus the whole region between thirty-eight and forty-one was left open to the enterprise of both companies; but to render angry collision impossible, the charter contained the judicious clause above noted, by which each colony might claim exclusive right fifty miles north or south of its extreme settlements, and thus neither could approach within one hundred miles of the other.

The hope of gold and silver from America was yet clinging with tenacity to the English mind. James grants to the companies unlimited right to dig and obtain the precious and other metals, but reserves to himself one-fifth of all the gold and silver and one-fifteenth of all the copper that might be discovered. Immediately after this clause we find a section granting to the councils for the colonies authority to coin money and use it among the settlers and natives. This permission may excite some surprise when we remember that the right to coin has been always guarded with peculiar jealousy by English monarchs, and that this constituted one serious charge against the Massachusetts colony in the unjust proceedings by which her charter was wrested from her in subsequent years.

To the companies was given power to carry settlers to Virginia and plant them upon her soil, and no restriction was annexed to this authority except that none should be taken from the realm upon whom the King should lay his injunction to remain. The colonists were permitted to have arms and to resist and repel all intruders from foreign states; and it was provided that none should trade and traffic within the colonies unless they should pay or agree to pay to the treasurers of the companies 2½ per cent, on their stock in trade if they were English subjects, and 5 per cent, if they were aliens. The sums so paid were to be appropriated to the company for twenty-one years from the date of the patent, and afterward were transferred to the crown. James never forgot a prospect for gain, and could not permit the colonists to enjoy forever the customs which, as consumers of foreign goods, they must necessarily have paid from their resources.

The jealous policy which at this time forbade the exportation, without license, of English products to foreign countries, has left its impress upon this charter. The colonists were, indeed, allowed to import all “sufficient shipping and furniture of armor, weapons, ordinance, powder, victual, and all other things necessary,” without burdensome restraint; but it was provided that if any goods should be shipped from England or her dependencies “with pretense” to carry them to Virginia, and should afterward be conveyed to foreign ports, the goods there conveyed and the vessel containing them should be absolutely forfeited to his majesty, his heirs and successors.

The lands held in the colonies were to be possessed by their holders under the most favorable species of tenure known to the laws of the mother-country. King James had never admired the military tenure entailed upon England by the feudal system, and he had made a praiseworthy though unsuccessful effort to reduce them all to the form of “free and common soccage,” a mode of holding land afterward carried into full effect under Charles II, and which, if less pervaded by the knightly spirit of feudal ages, was more favorable to the holder and more congenial with the freedom of the English constitution. This easy tenure was expressly provided for the lands of the new country; and it is a happy circumstance that America has been little affected even by the softened bonds thus early imposed upon her.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.