Subsidiary to the great design of philanthropy was the further purpose of making Georgia a silk, wine, oil, and drug-growing colony.

Continuing Settlement of Georgia,

our selection from History of Georgia by William B. Stevens published in 1847. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Settlement of Georgia.

Time: 1732

Place: Savannah

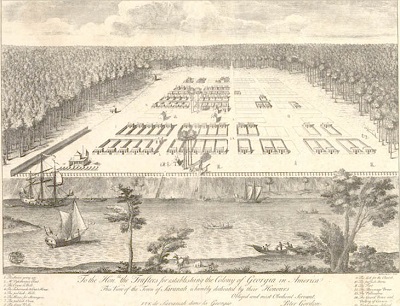

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Oglethorpe, in his New and Accurrate Account, declares:

These trustees not only give land to the unhappy who go thither, but are also empowered to receive the voluntary contributions of charitable persons to enable them to furnish the poor adventurers with all necessaries for the expense of the voyage, occupying the land, and supporting them till they find themselves comfortably settled. So that now the unfortunate will not be obliged to bind themselves to a long servitude, to pay for their passage, for they may be carried gratis into a land of liberty and plenty, where they immediately find themselves in possession of a competent estate in a happier climate than they knew before; and they are unfortunate, indeed, if here they cannot forget their sorrows.”

This was the main purpose of the settlement; and such noble views were “worthy to be the source of an American republic.”

Other colonies had been planted by individuals and companies for wealth and dominion; but the trustees of this, at their own desire, were restrained by the charter “from receiving any grant of lands in the province, or any salary, fee, perquisite, or profit whatsoever, by or from this undertaking.” The proprietors of other colonies were looking to their own interests; the motto of the trustees of this was “Non sibi, sed aliis.” The proprietors of other colonies were anxious to build up cities and erect states that should bear their names to a distant posterity; the trustees of this only busied themselves in erecting an asylum, whither they invited the indigent of their own and the exiled Protestants of other lands. It was the first colony ever founded by charity. New England had been settled by Puritans, who fled thither for conscience’ sake; New York by a company of merchants and adventurers in search of gain; Maryland, by papists retiring from Protestant intolerance; Virginia, by ambitious cavaliers; Carolina by the scheming and visionary Shaftesbury, and others, for private aims and individual aggrandizement; but Georgia was planted by the hand of benevolence, and reared into being by the nurturings of a disinterested charity.

But the colony was not to be confined to the poor and unfortunate. The trustees granted portions of five hundred acres to such as went over at their own expense, on condition that they carried over one servant to every fifty acres, and did military service in time of war or alarm. Thus the materials of the new colony consisted of three classes: the upper, or large landed proprietors and officers; the middle, or freeholders, sent over by the trustees; and the servants indented to that corporation or to private individuals.

Subsidiary to the great design of philanthropy was the further purpose of making Georgia a silk, wine, oil, and drug-growing colony. “Lying,” as the trustees remark, “about the same latitude with part of China, Persia, Palestine, and the Madeiras, it is highly probable that when hereafter it shall be well peopled and rightly cultivated England may be supplied from thence with raw silk, wine, oil, dyes, drugs, and many other materials for manufactures which she is obliged to purchase from southern countries.”

Such were the principal purposes of the trustees in settling Georgia. Extravagance was their common characteristic; for in the excited visions of its enthusiastic friends, Georgia was not only to rival Virginia and South Carolina, but to take the first rank in the list of provinces depending on the British Crown. Neither the El Dorado of Raleigh nor the Utopia of More could compare with the garden of Georgia; and the poet, the statesman, and the divine lauded its beauties and prophesied its future greatness. Oglethorpe, in particular, was quite enthusiastic in his description of the climate, soil, productions, and beauties of this American Canaan. “Such an air and soil,” he writes, “can only be fitly described by a poetical pen, because there is but little danger of exceeding the truth.”

With such blazoned exaggerations, strengthened by the interested efforts of a noble and learned body of trustees, and by the personal supervision of its distinguished originator, it is no matter of wonder that all Europe was aroused to attention; and that Swiss and German, Scotch and English, alike pressed forward to this promised land. Appeals were made by the trustees to the liberal, the philanthropic, the public-spirited, the humane, the patriotic, the Christian, to aid in this design of mercy, closing their arguments with the noble thought: “To consult the welfare of mankind, regardless of any private views, is the perfection of virtue, as the accomplishing and consciousness of it are the perfection of happiness.”

These preliminaries settled, we are brought to the period when the plan, the charity, the labors of the trustees, were to be put into efficient operation. Fortunate was it for the corporation that they had among their number one whose benevolence, whose fortune, and whose patriotism, as well as his military distinction conspired to make him the fittest leader and pioneer of so noble an undertaking. That one was James Oglethorpe, the originator, the chief promotor, the most zealous advocate of the colony; an honor conceded by his associates, and acknowledged by all.

We are brought now to the dock-yard at Deptford, to behold the first embarkation of the Georgia pilgrims.

The trustees, having selected from the throng of emigrants thirty-five families, numbering in all about one hundred twenty-five “sober, industrious, and moral persons,” chartered the Ann, a galley of two hundred tons, Captain John Thomas, and stationed her at Deptford, four miles below London, to receive her cargo and passengers. In the meantime the men were drilled to arms by sergeants of the guards; and all needed stores were gathered to make them comfortable on the voyage and to establish them on land.

It was not until the early part of November that the embarkation was ready for sailing.

On the 16th they were visited by the trustees, “to see nothing was wanting, and to take leave” of Oglethorpe; and having called the families separately before them in the great cabin they inquired if they liked their usage and voyage; or if they had rather return, giving them even then the alternative of remaining in England if they preferred it; and having found but one man who declined — on account of his wife, left sick in Southwark — they bid Oglethorpe and the emigrants an affectionate farewell. The ship sailed the next day, November 17, 1732, from Gravesend, skirted slowly along the southern coast of England, and, taking its departure from Sicily light, spread out its white sails to the breezes of the Atlantic.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Settlement of Georgia here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.