King Stephen, therefore, with his infantry, stood alone in the midst of the enemy.

Continuing Stephen Versus Matilda,

our selection from The Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1880. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Stephen Versus Matilda.

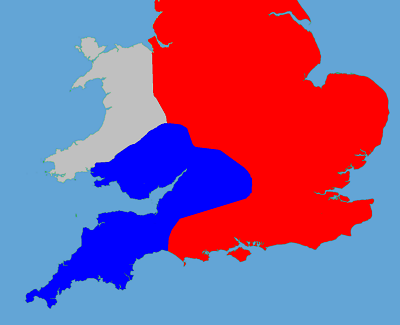

Time: 1135-1154

Place: England

Red is Stephen’s; Blue is Matilda’s

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Freebooters came over from Flanders, not to practice the industrial arts as in the time of Henry I, but to take their part in the general pillage. There was frightful scarcity in the country, and the ordinary interchange of man with man was unsettled by the debasement of the coin. “All things,” says Malmesbury, “became venial in England; and churches and abbeys were no longer secretly but even publicly exposed to sale.” All things become venial, under a government too weak to repress plunder or to punish corruption. The strong aim to be rich by rapine, and the cunning by fraud, when the confusion of a kingdom is grown so great that, as is recorded of this period, “the neighbor could put no faith in his nearest neighbor, nor the friend in his friend, nor the brother in his own brother.” The demoralization of anarchy is even more terrible than its bloodshed.

The marches and sieges, the revolts and treacheries, of this evil time are occasionally varied by incidents which illustrate the state of society. Robert Fitz-Herbert, with a detachment of the Earl of Gloucester’s soldiers, surprised the castle of Devizes, which the King had taken from the Bishop of Salisbury. Robert Fitz-Herbert varies the atrocities of his fellow-barons, by rubbing his prisoners with honey, and exposing them naked to the sun. But Robert, having obtained Devizes, refused to admit the Earl of Gloucester to any advantage of its possession, and commenced the subjection of the neighborhood on his own account. Another crafty baron, John Fitz-Gilbert, held the castle of Marlborough; and Robert Fitz-Herbert, having an anxious desire to be lord of that castle also, endeavoring to cajole Fitz-Gilbert into the admission of his followers, went there as a guest, but was detained as a prisoner. Upon this the Earl of Gloucester came in force for revenge against his treacherous ally, Fitz-Herbert, and, conducting him to Devizes, there hanged him. The surprise of Lincoln Castle, upon which the events of 1141 mainly turned, is equally characteristic of the age. Ranulf, Earl of Chester, and William de Roumare, his half-brother, were avowed friends of King Stephen. But their ambition took a new direction for the support of Matilda. The garrison of Lincoln had no apprehension of a surprise, and were busy in those sports which hardy men enjoy even amid the rougher sport of war. The Countess of Chester and her sister-in-law, with a politeness that the ladies of the court of Louis le Grand could not excel, paid a visit to the wife of the knight who had the defence of the castle. While there, at this pleasant morning call, “talking and joking” with the unsuspecting matron, as Ordericus relates, the Earl of Chester came in, “without his armor or even his mantle,” attended only by three soldiers. His courtesy was as flattering as that of his countess and her friend. But his men-at-arms suddenly mastered the unprepared guards, and the gates were thrown open to Earl William and his numerous followers. The earls, after this stratagem, held the castle against the King, who speedily marched to Lincoln. But the Earl of Chester contrived to leave the castle, and soon raised a powerful army of his own vassals. The Earl of Gloucester joined him with a considerable force, and they together advanced to the relief of the besieged city. The battle of Lincoln was preceded by a trifling incident to which the chroniclers have attached importance. It was the Feast of the Purification; and at the mass which was celebrated at the dawn of day, when the King was holding a lighted taper in his hand it was suddenly extinguished. “This was an omen of sorrow to the King,” says Hoveden. But another chronicler, the author of the Gesta Stephain, tells us, in addition, that the wax candle was suddenly relighted; and he accordingly argues that this incident was “a token that for his sins he should be deprived of his crown, but on his repentance, through God’s mercy, he should wonderfully and gloriously recover it.” The King had been more than a month laying siege to the castle, and his army was encamped around the city of Lincoln. When it was ascertained that his enemies were at hand he was advised to raise the siege and march out to strengthen his power by a general levy. He decided upon instant battle. He was then exhorted not to fight on the solemn festival of the Purification. But his courage was greater than his prudence or his piety. He set forth to meet the insurgent earls. The best knights were in his army; but the infantry of his rivals was far more numerous. Stephen detached a strong body of horse and foot to dispute the passage of a ford of the Trent. But Gloucester by an impetuous charge obtained possession of the ford, and the battle became general. The King’s horsemen fled. The desperate bravery of Stephen, and the issue of the battle, have been described by Henry of Huntingdon with singular animation: “King Stephen, therefore, with his infantry, stood alone in the midst of the enemy. These surrounded the royal troops, attacking the columns on all sides, as if they were assaulting a castle. Then the battle raged terribly round this circle; helmets and swords gleamed as they clashed, and the fearful cries and shouts reechoed from the neighboring hills and city walls. The cavalry, furiously charging the royal column, slew some and trampled down others; some were made prisoners. No respite, no breathing time, was allowed; except in the quarter in which the King himself had taken his stand, where the assailants recoiled from the unmatched force of his terrible arm. The Earl of Chester seeing this, and envious of the glory the King was gaining, threw himself upon him with the whole weight of his men-at-arms. Even then the King’s courage did not fail, but his heavy battle-axe gleamed like lightning, striking down some, bearing back others. At length it was shattered by repeated blows. Then he drew his well-tried sword, with which he wrought wonders, until that too was broken. Perceiving which, William de Kaims, a brave soldier, rushed on him, and seizing him by his helmet, shouted, ‘Here, here, I have taken the King!’ Others came to his aid, and the King was made prisoner.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.