After trapping her in Castle Arundel, in the most romantic spirit of chivalry he permitted the Empress to pass out, and to set forward to join her brother at Bristol, under a safe-conduct.

Continuing Stephen Versus Matilda,

our selection from The Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1880. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Stephen Versus Matilda.

Time: 1135-1154

Place: England

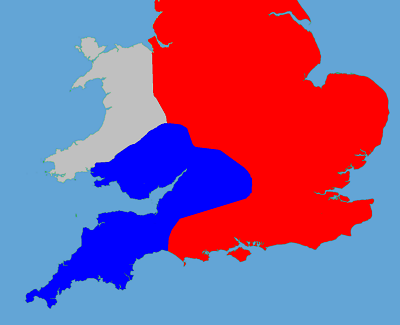

Red is Stephen’s; Blue is Matilda’s

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

We have briefly stated these few general facts regarding the outward manifestation of the power and the wealth of the Church at this period, to show how important an influence it must have exercised upon all questions of government. But its organization was of far greater importance than the aggregate wealth of the sees and abbeys. The English Church, during the troubled reign of Stephen, had become more completely under the papal dominion than at any previous period of its history. The King attempted, rashly perhaps, but honestly, to interpose some check to the ecclesiastical desire for supremacy; but from the hour when he entered into a contest with bishops and synods, his reign became one of kingly trouble and national misery.

The Norman bishops not only combined in their own persons the functions of the priest and of the lawyer, but were often military leaders. As barons they had knight-service to perform; and this condition of their tenures naturally surrounded them with armed retainers. That this anomalous position should have corrupted the ambitious churchman into a proud and luxurious lord was almost inevitable. The authority of the Crown might have been strong enough to repress the individual discontent, or to punish the individual treason, of these great prelates; but every one of them was doubly formidable as a member of a confederacy over which a foreign head claimed to preside. There were three bishops whose intrigues King Stephen had especially to dread at the time when an open war for the succession of Matilda was on the point of bursting forth. Roger, the Bishop of Salisbury, had been promoted from the condition of a parish priest at Caen, to be chaplain, secretary, chancellor, and chief justiciary of Henry I. He was instrumental in the election of Stephen to the throne; and he was rewarded with extravagant gifts, as he had been previously rewarded by Henry. Stephen appears to have fostered his rapacity, in the conviction that his pride would have a speedier fall; the King often saying, “I would give him half England, if he asked for it: till the time be ripe he shall tire of asking ere I tire of giving.” The time was ripe in 1139. The Bishop had erected castles at Devizes, at Sherborne, and at Malmesbury. King Henry had given him the castle of Salisbury. This lord of four castles had powerful auxiliaries in his nephews, the Bishop of Lincoln and the Bishop of Ely. Alexander of Lincoln had built the castles of Newark and Sleaford, and was almost as powerful as his uncle. In July, 1139, a great council was held at Oxford; and thither came these three bishops with military and secular pomp, and with an escort that became “the wonder of all beholders.” A quarrel ensued between the retainers of the bishops and those of Alain, Earl of Brittany, about a right to quarters; and the quarrel went on to a battle, in which men were slain on both sides. The bishops of Salisbury and Lincoln were arrested, as breakers of the king’s peace. The Bishop of Ely fled to his uncle’s castle of Devizes. The King, under the advice of the sagacious Earl Millent, resolved to dispossess these dangerous prelates of their fortresses, which were all finally surrendered. “The bishops, humbled and mortified, and stripped of all pomp and vainglory, were reduced to a simple ecclesiastical life, and to the possessions belonging to them as churchmen.” The contemporary who writes this — the author of the Gesta Stephani — although a decided partisan of Stephen, speaks of this event as the result of mad counsels, and a grievous sin that resembled the wickedness of the sons of Korah and of Saul. The great body of the ecclesiastics were indignant at what they considered an offence to their order. The Bishop of Winchester, the brother of Stephen, had become the Pope’s legate in England, and he summoned the King to attend a synod at Winchester. He there produced his authority as legate from Pope Innocent, and denounced the arrest of the bishops as a dreadful crime. The King had refused to attend the council, but he sent Alberic de Vere, “a man deeply versed in legal affairs,” to represent him. This advocate urged that the Bishop of Lincoln was the author of the tumult at Oxford; that whenever Bishop Roger came to court, his people, presuming on his power, excited tumults; that the Bishop secretly favored the King’s enemies, and was ready to join the party of the Empress. The council was adjourned, but on a subsequent day came the Archbishop of Rouen, as the champion of the King, and contended that it was against the canons that the bishops should possess castles; and that even if they had the right, they were bound to deliver them up to the will of the King, as the times were eventful, and the King was bound to make war for the common security. The Archbishop of Rouen reasoned as a statesman; the Bishop of Winchester as the Pope’s legate. Some of the bishops threatened to proceed to Rome; and the King’s advocate intimated that if they did so, their return might not be so easy. Swords were at last unsheathed. The King and the earls were now in open hostility with the legate and the bishops. Excommunication of the King was hinted at; but persuasion was resorted to. Stephen, according to one authority, made humble submission, and thus “abated the rigor of ecclesiastical discipline.” If he did submit, his submission was too late. Within a month Earl Robert and the empress Matilda were in England.

Matilda and the Earl of Gloucester landed at Arundel, where the widow of Henry I was dwelling. They had a very small force to support their pretensions. The Earl crossed the country to Bristol. “All England was struck with alarm, and men’s minds were agitated in various ways. Those who secretly or openly favored the invaders were roused to more than usual activity against the King, while his own partisans were terrified as if a thunderbolt had fallen.” Stephen invested the castle of Arundel. But in the most romantic spirit of chivalry he permitted the Empress to pass out, and to set forward to join her brother at Bristol, under a safe-conduct. In 1140 the whole kingdom appears to have been subjected to the horrors of a partisan warfare. The barons in their castles were making a show of “defending their neighborhoods, but, more properly to speak, were laying them waste.” The legate and the bishops were excommunicating the plunderers of churches, but the plunderers laughed at their anathemas.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.