Whatever was the misery of the country, the ordinary family ties still bound the people to the universal Christian church, whether the priest were Norman or English.

Continuing Stephen Versus Matilda,

our selection from The Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1880. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Stephen Versus Matilda.

Time: 1135-1154

Place: England

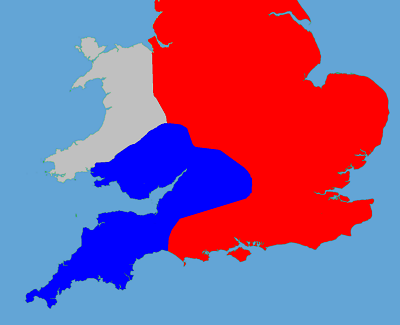

Red is Stephen’s; Blue is Matilda’s

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Henry I founded the Abbey of Reading, but the mimus of Henry I built the priory and hospital of St. Bartholomew. This “pleasant-witted gentleman,” as Stow calls the royal mimus (which Percy interprets “minstrel”), having, according to the legend, “diverted the palaces of princes with courtly mockeries and triflings” for many years, bethought himself at last of more serious matters, and went to do penance at Rome. He returned to London; and obtaining a grant of land in a part of the King’s market of Smithfield, which was a filthy marsh where the common gallows stood, there erected the priory, whose Norman arches as satisfactorily attest its date as Henry’s charter. The piety of a court jester in the twelfth century, when the science of medicine was wholly empirical, founded one of the most valuable medical schools of the nineteenth century. The desire to raise up splendid churches in the place of the dilapidated Saxon buildings was a passion with Normans, whether clerics or laymen. Ralph Flambard, the bold and unscrupulous minister of William II, erected the great priory of Christchurch, in his capacity of bishop. But he raised the necessary funds with his usual financial vigor. He took the revenues of the canons into his hands, and put the canons upon a short allowance till the work was completed. The Cistercian order of monks was established in England late in the reign of Henry I. Their rule was one of the most severe mortification and of the strictest discipline. Their lives were spent in labor and in prayer, and their one frugal daily meal was eaten in silence. While other religious orders had their splendid abbeys amid large communities, the Cistercians humbly asked grants of land in the most solitary places, where the recluse could meditate without interruption by his fellow-men, amid desolate moors and in the uncultivated gorges of inaccessible mountains. In such a barren district Walter l’Espée, who had fought at Northallerton, founded Rievaulx Abbey. It was “a solitary place in Blakemore,” in the midst of hills. The Norman knight had lost his son, and here he derived a holy comfort in seeing the monastic buildings rise under his munificent care, and the waste lands become fertile under the incessant labors of the devoted monks. The ruins of Tintern Abbey and Melrose Abbey, whose solemn influences have inspired the poets of our own age with thoughts akin to the contemplations of their Cistercian founders, belong to a later period of ecclesiastical architecture; for the dwellings of the original monks have perished, and the “broken arches,” and “shafted oriel,” the “imagery,” and “the scrolls that teach thee to live and die,” speak of another century, when the Norman architecture, like the Norman character, was losing its distinctive features and becoming “Early English.” We dwell a little upon these Norman foundations, to show how completely the Church was spreading itself over the land, and asserting its influence in places where man had seldom trod, as well as in populous towns, where the great cathedral was crowded with earnest votaries, and the lessons of peace were proclaimed amid the distractions of unsettled government and the oppressions of lordly despotism. Whatever was the misery of the country, the ordinary family ties still bound the people to the universal Christian church, whether the priest were Norman or English. The new-born infant was dipped in the great Norman font, as the children of the Confessor’s time had been dipped in the ruder Saxon. The same Latin office, unintelligible in words, but significant in its import, was said and sung when the bride stood at the altar and the father was laid in his grave. The vernacular tongue gradually melted into one dialect; and the penitent and the confessor were the first to lay aside the great distinction of race and country — that of language.

The Norman prelates were men of learning and ability, of taste and magnificence; and, whatever might have been the luxury and even vices of some among them, the vast revenues of the great sees were not wholly devoted to worldly pomp, but were applied to noble uses. After the lapse of seven centuries we still tread with reverence those portions of our cathedrals in which the early Norman architecture is manifest. There is no English cathedral in which we are so completely impressed with the massive grandeur of the round-arched style as by Durham. Durham Cathedral was commenced in the middle of the reign of Rufus, and the building went on through the reign of Henry I. Canterbury was commenced by Archbishop Lanfranc, soon after the Conquest, and was enlarged and altered in various details, till it was burned in 1174. Some portions of the original building remain. Rochester was commenced eleven years after the Conquest; and its present nave is an unaltered part of the original building. Chichester has nearly the same date of its commencement; and the building of this church was continued till its dedication in 1148. Norwich was founded in 1094, and its erection was carried forward so rapidly that in seven years there were sixty monks here located. Winchester is one of the earliest of these noble cathedrals; but its Norman feature of the round arch is not the general characteristic of the edifice, the original piers having been recased in the pointed style, in the reign of Edward III. The dates of these buildings, so grand in their conception, so solid in their execution, would be sufficient of themselves to show the wealth and activity of the Church during the reigns of the Conqueror and his sons. But, during this period of seventy years, and in part of the reign of Stephen, the erection of monastic buildings was universal in England, as in Continental Europe. The crusades gave a most powerful impulse to the religious fervor. In the enthusiasm of chivalry, which covered many of its enormities with outward acts of piety, vows were frequently made by wealthy nobles that they would depart for the Holy Wars. But sometimes the vow was inconvenient. The lady of the castle wept at the almost certain perils of her lord, and his projects of ambition often kept the lord at home to look after his own especial interests. Then the vow to wear the cross might be commuted by the foundation of a religious house. Death-bed repentance for crimes of violence and a licentious life increased the number of these endowments. It has been computed that three hundred monastic establishments were founded in England during the reigns of Henry I, Stephen, and Henry II.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.