Today’s installment concludes Stephen Versus Matilda,

our selection from The Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1880.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of nine thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Stephen Versus Matilda.

Time: 1135-1154

Place: England

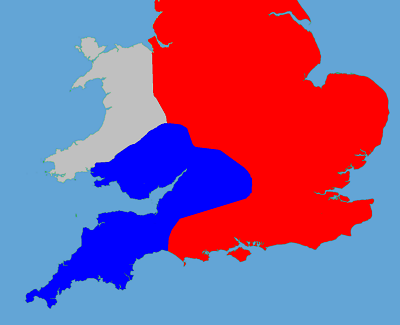

Red is Stephen’s; Blue is Matilda’s

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In 1142 the civil war is raging more fiercely than ever. Matilda is at Oxford, a fortified city, protected by the Thames, by a wall, and by an impregnable castle. Stephen, with a body of veterans, wades across the river and enters the city. Matilda and her followers take refuge in the keep. For three months the King presses the siege, surrounding the fortress on all sides. Famine is approaching to the helpless garrison. It is the Christmas season. The country is covered with a deep snow. The Thames and the tributary rivers are frozen over. With a small escort Matilda contrives to escape, and passes undiscovered through the royal posts, on a dark and silent night, when no sound is heard but the clang of a trumpet or the challenge of a sentinel. In the course of the night she went to Abingdon on foot, and afterwards reached Wallingford on horseback. The author of the Gesta Stephani expresses his wonder at the marvellous escapes of this courageous woman. The changes of her fortune are equally remarkable. After the flight from Oxford the arms of the Earl of Gloucester are again successful. Stephen is beaten at Wilton, and retreats precipitately with his military brother, the Bishop of Winchester. There are now in the autumn of 1142 universal turmoil and desolation. Many people emigrate. Others crowd round the sanctuary of the churches, and dwell there in mean hovels. Famine is general. Fields are white with ripened corn, but the cultivators have fled, and there is none to gather the harvest. Cities are deserted and depopulated. Fierce foreign mercenaries, for whom the barons have no pay, pillage the farms and the monasteries. The bishops, for the most part, rest supine amid all this storm of tyranny. When they rouse themselves they increase rather than mitigate the miseries of the people. Milo, Earl of Hereford, has demanded money of the Bishop of Hereford to pay his troops. The Bishop refuses, and Milo seizes his lands and goods. The Bishop then pronounces sentence of excommunication against Milo and his adherents, and lays an interdict upon the country subject to the Earl’s authority. We might hastily think that the solemn curse pronounced against a nation, or a district, was an unmeaning ceremony, with its “bell, book, and candle,” to terrify only the weak-minded. It was one of the most outrageous of the numerous ecclesiastical tyrannies. The consolations of religion were eagerly sought for and justly prized by the great body of the people, who earnestly believed that a happy future would be a reward for the patient endurance of a miserable present. As they were admitted to the holy communion, they recognized an acknowledgment of the equality of men before the great Father of all. Their marriages were blessed and their funerals were hallowed. Under an interdict all the churches were shut. No knell was tolled for the dead, for the dead remained unburied. No merry peals welcomed the bridal procession, for no couple could be joined in wedlock. The awe-stricken mother might have her infant baptized, and the dying might receive extreme unction. But all public offices of the Church were suspended. If we imagine such a condition of society in a village devastated by fire and sword, we may wonder how a free government and a Christian church have ever grown up among us.

If Stephen had quietly possessed the throne, and his heir had succeeded him, the crowns of England and Normandy would have been disconnected before the thirteenth century. Geoffrey of Anjou, while his duchess was in England, had become master of Normandy, and its nobles had acknowledged his son Henry as their rightful duke. The boy was in England, under the protection of the Earl of Gloucester, who attended to his education. The great Earl died in 1147. For a few years there had been no decided contest between the forces of the King and the Empress. After eight years of terrible hostility, and of desperate adventure, Matilda left the country. Stephen made many efforts to control the license of the barons, but with little effect. He was now engaged in another quarrel with the Church. His brother had been superseded as legate by Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, in consequence of the death of the Pope who had supported the Bishop of Winchester. Theobald was Stephen’s enemy, and his hostility was rendered formidable by his alliance with Bigod, the Earl of Norfolk. The Archbishop excommunicated Stephen and his adherents, and the King was enforced to submission. In 1150 Stephen, having been again reconciled to the Church, sought the recognition of his son Eustace as the heir to the kingdom. This recognition was absolutely refused by the Archbishop, who said that Stephen was regarded by the papal see as an usurper. But time was preparing a solution of the difficulties of the kingdom. Henry of Anjou was grown into manhood. Born in 1133, he had been knighted by his uncle, David of Scotland, in 1149. His father died in 1151, and he became not only Duke of Normandy, but Earl of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine. In 1152 he contracted a marriage of ambition with Eleanor, the divorced wife of Louis of France, and thus became Lord of Aquitaine and Poitou, which Eleanor possessed in her own right. Master of all the western coast of France, from the Somme to the Pyrenees, with the exception of Brittany, his ambition, thus strengthened by his power, prepared to dispute the sovereignty of England with better hopes than ever waited on his mother’s career. He landed with a well-appointed band of followers in 1153, and besieged various castles. But no general encounter took place. The King and the Duke had a conference, without witnesses, across a rivulet, and this meeting prepared the way for a final pacification. The negotiators were Henry, the Bishop, on the one part, and Theobald, the Archbishop, on the other. Finally Stephen led the Prince in solemn procession through the streets of Winchester, “and all the great men of the realm, by the King’s command, did homage, and pronounced the fealty due to their liege lord, to the Duke of Normandy, saving only their allegiance to King Stephen during his life.” Stephen’s son Eustace had died during the negotiations. The troublesome reign of Stephen was soon after brought to a close. He died on the 25th of October, 1154. His constant and heroic queen had died three years before him.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Stephen Versus Matilda by Charles Knight from his book The Popular History of England published in 1880. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Stephen Versus Matilda here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.