This series has nine easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Stephen Crowned.

Introduction

This story describes an important development in the role and status of women in western civilization. Note the outcome: Henry II inheriting the throne through his mother. While women rule was still disputed, their inheritance rights was significantly modified. This English idea would have a central role in the dispute of the Hundred Years War a couple centuries later. But first some specific background to this one.

William the Conqueror, King of England, was succeeded by his sons William Rufus and Henry — on account of his scholarship known as Beauclerc. Prince William, Henry’s only son, was drowned when starting from Normandy for England in 1120. In the absence of male issue Henry settled the English and Norman crowns upon his daughter Matilda, and demanded an oath of fidelity to her from the barons.

Matilda had been married first to Emperor Henry V of Germany, who died in 1125, and secondly to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou.

Stephen was the son of Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror, who had married Stephen, Count of Blois. Stephen, with his brother Henry, had been invited to the court of England by their uncle, and had received honors, preferments, and riches. Henry becoming an ecclesiast was created abbot of Glastonbury and bishop of Winchester. Stephen, among other possessions, received the great estate forfeited by Robert Mallet in England, and that forfeited by the Earl of Mortaigne in Normandy. By his marriage with Matilda, daughter of the Earl of Boulogne, he had succeeded also to the territories of his father-in-law. Stephen by studied arts and personal qualities became a great favorite with the English barons and the people.

The empress Matilda and her husband Geoffrey, unfortunately, were unpopular both in England and Normandy, the English barons especially viewing with disfavor the prospect of a woman occupying the throne.

Henry Beauclerc died in 1135 at his favorite hunting-seat, the Castle of Lions, near Rouen, in Normandy. Stephen, ignoring the oath of fealty to the daughter of his benefactor, hastened to England, and, notwithstanding some opposition, with the help of his clerical brother and other functionaries had himself proclaimed and crowned king. This act involved England in years of civil war, anarchy, and wretchedness, which ended only with the accession as Henry II of Empress Matilda’s son, Henry Plantagenet of Anjou.

This selection is from The Popular History of England by Charles Knight published in 1880. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Charles Knight was an English publisher, editor and author. He published and contributed to works such as The Penny Magazine, The Penny Cyclopaedia, and The English Cyclopaedia, and established the Local Government Chronicle.

Time: 1135-1154

Place: England

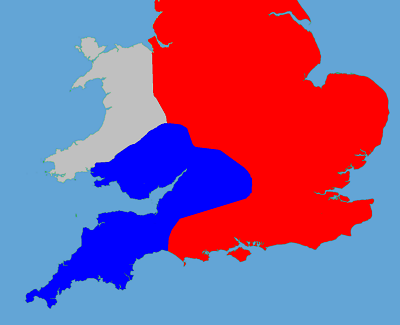

Red is Stephen’s; Blue is Matilda’s

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Of the reign of Stephen, Sir James Mackintosh has said, “It perhaps contains the most perfect condensation of all the ills of feudality to be found in history.” He adds, “The whole narrative would have been rejected, as devoid of all likeness to truth, if it had been hazarded in fiction.” As a picture of “all the ills of feudality,” this narrative is a picture of the entire social state — the monarchy, the Church, the aristocracy, the people — and appears to us, therefore, to demand a more careful examination than if the historical interest were chiefly centered in the battles and adventures belonging to a disputed succession, and in the personal characters of a courageous princess and her knightly rival.

Stephen, Earl of Boulogne, the nephew of King Henry I, was no stranger to the country which he aspired to rule. He had lived much in England and was a universal favorite. “From his complacency of manners, and his readiness to joke, and sit and regale even with low people, he had gained so much on their affections as is hardly to be conceived.” This popular man was at the death-bed of his uncle; but before the royal body was borne on the shoulders of nobles from the Castle of Lions to Rouen, Stephen was on his road to England. He embarked at Whitsand, undeterred by boisterous weather, and landed during a winter storm of thunder and lightning. It was a more evil omen when Dover and Canterbury shut their gates against him. But he went boldly on to London. There can be no doubt that his proceedings were not the result of a sudden impulse, and that his usurpation of the crown was successful through a very powerful organization. His brother Henry was Bishop of Winchester; and his influence with the other dignitaries of the Church was mainly instrumental in the election of Stephen to be king, in open disregard of the oaths taken a few years before to recognize the succession of Matilda and of her son. Between the death of a king and the coronation of his successor there was usually a short interval, in which the form of election was gone through. But it is held that during that suspension of the royal functions there was usually a proclamation of “the king’s peace,” under which all violations of law were punished as if the head of the law were in the full exercise of his functions and dignities. King Henry I died on the 1st of December, 1135. Stephen was crowned on the 26th of December. The death of Henry would probably have been generally known in England in a week after the event. There is a sufficient proof that this succession was considered doubtful, and, consequently, that there was an unusual delay in the proclamation of “the king’s peace.” The Forest Laws were the great grievance of Henry’s reign. His death was the signal for their violation by the whole body of the people. “It was wonderful how so many myriads of wild animals, which in large herds before plentifully stocked the country, suddenly disappeared, so that out of the vast number scarcely two now could be found together. They seemed to be entirely extirpated.” According to the same authority, “the people also turned to plundering each other without mercy”; and “whatever the evil passions suggested in peaceable times, now that the opportunity of vengeance presented itself, was quickly executed.” This is a remarkable condition of a country which, having been governed by terror, suddenly passed out of the evils of despotism into the greater evils of anarchy. This temporary confusion must have contributed to urge on the election of Stephen. By the Londoners he was received with acclamations; and the witan chose him for king without hesitation, as one who could best fulfil the duties of the office and put an end to the dangers of the kingdom.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.