This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Napoleon Elected Emperor.

Introduction

The French Revolution did not set up a legitimate government, according to the rest of Europe. Even in America, when the French government asked that the USA honor its alliance per the Treaty of 1778, President Washington refused, on the grounds that the treaty was with the government of Louis XVI, not the republican French government. So, when the French were attacked by almost the whole of Europe, they were alone.

Then came Napoleon and his victories.

The Battle of the Nile left Napoleon and his army practically imprisoned in Egypt, held there by British ships. In their absence affairs in Europe went badly for France. A fresh coalition was formed against her in which Russia joined, and Suvarov, the great Russian General, drove the French from Italy. Napoleon, leaving his army, slipped back secretly to France and was welcomed with intense enthusiasm. He at once undertook a revolution of his own. Appealing to his old comrades of the army, he declared the members of the Government inefficient and turned them out of office. A new Constitution was established and Bonaparte was made “First Consul,” an office that practically centered all power in his own hands (1799).

From this time, the Republic was practically at an end, Napoleon was dictator, though the empty forms of republicanism continued for another five years. Under the First Consul’s direction the French soldiers reestablished their military supremacy. General Moreau won victory after victory in Germany and finally crushed the Austrians at Hohenlinden. Napoleon himself led an army over the Alps, and surprised and overthrew the Austrians in Italy. He dictated a peace in which all Europe joined (1802). Even England for a time abandoned the strife, though she soon renewed it. Napoleon seized the brief respite to establish extensive internal reforms in France and to consolidate his own power. The consulship had first been given to him for ten years, then it was made a life office.

Still the French regime’s legitimacy remained in doubt. Diplomatic setbacks abroad, unrest at home undermined the long-term prospects of France’s government and any conceivable future government (except for a possible Bourbon restoration). So, what was France’s – and Napoleon’s – options?

Hitherto there had never been more than two emperors, those of Germany whose title had descended through a thousand years and who were in some sort heirs of the Empire of Western Rome, and more recently the emperors of Russia, claiming to carry on the ancient Roman Empire of the East. The empire of Germany had practically ceased to exist, crushed under Napoleon’s blows. In 1804 the conqueror abandoned the last pretense of republicanism and had himself elected hereditary Emperor of the French.

This may not have been the best choice to end the French Revolution. The flaws in the foundation of the French Revolution limited the choices available. As a cry for legitimacy Napoleon’s decision was at least a plausible one.

This selection is from Life of Napoleon Buonaparte by William Hazlitt published in 1830. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

William Hazlitt is now considered one of the greatest critics and essayists in the history of the English language.

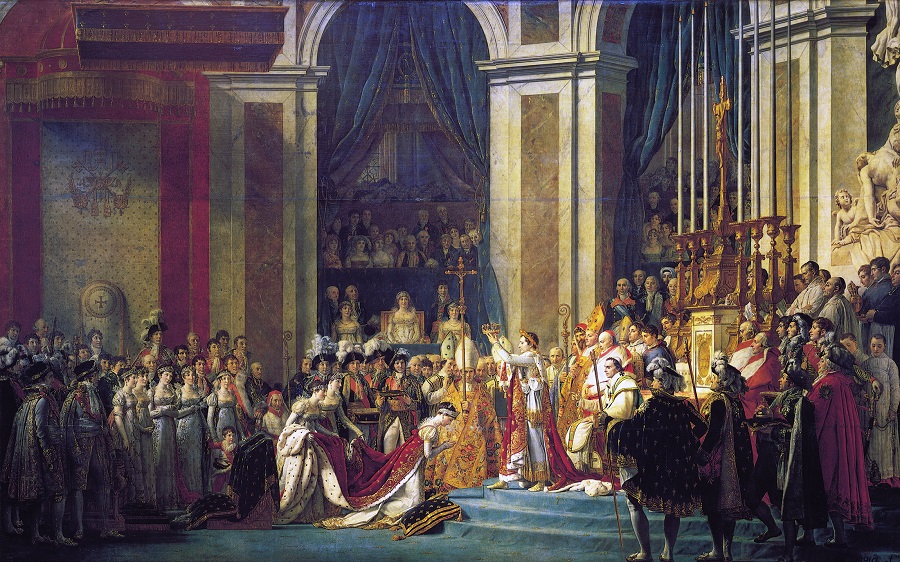

Time: 1804

Place: Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Repeated attempts made against the life of the First Consul gave an excuse for following up the design that had been for some time agitated of raising him to the imperial throne and making the dignity hereditary in his family. Not that indeed this would secure him from personal danger, though it is true that “there’s a divinity doth hedge a king”; but it lessened the temptation to the enterprise and allayed a part of the public disquietude by providing a successor. All or the greater part were satisfied — either from reason, indolence, or the fear of worse — with what had been gained by the Revolution, and did not wish to see it launch out again from the port in which it had taken shelter to seek the perils of new storms and quicksands. If prudence had some share in this measure, there can be little doubt that vanity and cowardice had theirs also — or that there was a lurking desire to conform to the Gothic dialect of civilized Europe in forms of speech and titles, and to adorn the steel arm of the Republic with embroidered drapery and gold tissue. The imitation, though probably not without its effect, {1} would look more like a burlesque to those whom it was intended to please, and could hardly flatter the just pride of those by whom it was under taken.

[1: For instance, would the Emperor of Austria have married his daughter to Bonaparte if he had been only First Consul ?—ED.]

The old Republican party made some stand: the Emigrants showed great zeal for it, partly real, partly affected. Fouché canvassed the Senate and the men of the Revolution, and was soon placed in consequence at the head of the police, which was restored, as it was thought that fresh intrigues might break out on the occasion. The army gave the first impulse, as was but natural; to them the change of style from Imperator to “Emperor” was but slight. All ranks and classes followed when the example was once set: the most obscure hamlets joined in the addresses; the First Consul received wagonloads of them. A register for the reception of votes for or against the question was opened in every parish in France — from Antwerp to Perpignan, from Brest to Mont Cenis.

The proces-verbal of all these votes was laid up in the archives of the Senate, who went in a body from Paris to St. Cloud to present it to the First Consul. The Second Consul Cambaceres read a speech, concluding with a summary of the number of votes; whereupon he in a loud voice proclaimed Napoleon Bonaparte Emperor of the French. The senators, placed in a line facing him, vied with each other in repeating “Vive l’Empereur!” and returned with all the outward signs of joy to Paris, where people were already writing epitaphs on the Republic. Happy they whom epitaphs on the dead console for the loss of them! This was the time, if ever, when they ought to have opposed him, and prescribed limits to his power and ambition, and not when he returned weather-beaten and winter-flawed from Russia. But it was more in character for these persons to cringe when spirit was wanted, and to show it when it was fatal to him and to themselves.

Thus, then the First Consul became emperor by a majority of two millions some hundred thousand votes, to a few hundreds. The number of votes is complained of by some persons as too small. Probably they may think that if the same number had been against the measure instead of being for it, this would have conferred a right as being in opposition to and in contempt of the choice of the people. What other candidate was there that would have got a hundred? What other competitor could indeed have come forward on the score of merit? Detur optimo. Birth there was not; but birth supersedes both choice and merit. The day after the inauguration, Bonaparte received the constituted bodies, the learned corporations, etc. The only strife was who should bow the knee the lowest to the new-risen sun. The troops while taking the oath rent the air with shouts of enthusiasm. The succeeding days witnessed the nomination of the new dignitaries, marshals, and all the usual appendages of a throne, as well with reference to the military appointments as to the high offices of the crown. On July 14th, the first distribution of the crosses of the Legion of Honor took place; and Napoleon set out for Boulogne to review the troops stationed in the neighborhood and distribute the decorations of the Legion of Honor among them, which thenceforth were substituted for weapons of honor, which had been previously awarded ever since the first war in Italy.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.