Bacon, though not himself a realist in the modern and abused sense of that term, was the father of realism.

Continuing Comenius Modernizes Education,

our selection from John Amos Comenius – Bishop of the Moravians, His Life and Educational Works by Simon Somerville Laurie published in 1892. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Comenius Modernizes Education.

Time: 1638

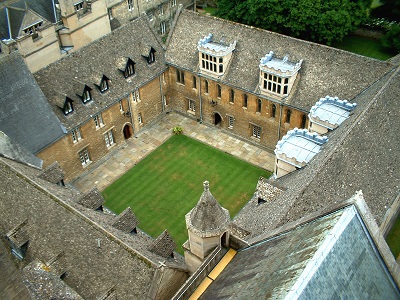

Place: Prague

CC BY-SA 2.5 image from Wikipedia.

The thought of any age determines the education of the age which is to succeed it. Education follows; it does not lead. The school and the church alike march in the wake of science, philosophy, and political ideas. We see this illustrated in every epoch of human history, and in none so conspicuously as in the changes which occurred in the philosophy and education of ancient Rome during the lifetime of the elder Cato, and in modern times during the revival of letters and the subsequent rise of the Baconian induction. It is impossible, indeed, for any great movement of thought to find acceptance without its telling to some extent on every department of the body politic. Its influence on the ideas entertained as to the education of the rising generation must be, above all, distinct and emphatic. Every philosophical writer on political science has recognized this, and has felt the vast significance of the educational system of a country both as an effect — the consequence of a revolution in thought — and as a cause, a moving force of incalculable power in the future life of a commonwealth. Thus it was that the humanistic movement which preceded and accompanied the Reformation of religion shook to its center the medieval school system of Europe; and that subsequently the silent rise of the inductive spirit subverted its foundations.

Bacon, though not himself a realist in the modern and abused sense of that term, was the father of realism. It was this side of his teaching which was greedily seized upon, and even exaggerated. Educational zeal now ran in this channel. The conviction of the churches of the time, that one can make men what one pleases — by fair means or foul — was shared by the innovators. By education, rightly conceived and rightly applied, the enthusiasts dreamed that they could manufacture men, and, in truth, the Jesuits had shown that a good deal could be done in this direction. The new enthusiasts failed to see that the genius of Protestantism is the genius of freedom, and that man refuses to be manufactured except on suicidal terms. He must first sacrifice that which is his distinctive title to manhood — his individuality and will. That the prophets of educational realism should have failed to see this is not to be laid at their door as a fault; it merely shows that they belonged to their own time, and not to ours. They failed then, as some fail now, to understand man and his education, because they break with the past. The record of the past is with them merely a record of blunders. The modern humanist more wisely accepts it as the storehouse of the thoughts and life of human reason. In the life of man each individual of the race best finds his own true life. This is modern humanism — the realism of thought.

Yet it is to the sense-realists of the earlier half of the seventeenth century that we owe the scientific foundations of educational method, and the only indication of the true line of answer to the complaints of the time. In their hands sense-realism became allied with Protestant theology, and pure humanism disappeared. They were represented first by Wolfgang von Ratich, a native of Holstein, born in 1571. Ratich was a man of considerable learning. The distractions of Europe, and the want of harmony, especially among the churches of the Reformation, led him to consider how a remedy might be found for many existing evils. He thought that the remedy was to be found in an improved school system — improved in respect both of the substance and method of teaching. In 1612, accordingly, he laid before the Diet of the German empire at Frankfort a memorial, in which he promised, “with the help of God, to give instruction for the service and welfare of all Christendom.”

The torch that fell from Ratich’s hand was seized, ere it touched the ground, by John Amos Comenius, who became the head, and still continues the head, of the sense-realistic school. His works have a present and practical, and not merely a historical and speculative, significance.

Not only had the general question of education engaged many minds for a century and more before Comenius arose, but the apparently subsidiary, yet all-important, question of method, in special relation to the teaching of the Latin tongue, had occupied the thoughts and pens of many of the leading scholars of Europe. The whole field of what we now call secondary instruction was occupied with the one subject of Latin; Greek, and occasionally Hebrew, having been admitted only in the beginning of the sixteenth century, and then only to a subordinate place. This of necessity. Latin was the one key to universal learning. To give to boys the possession of this key was all that teachers aimed at until their pupils were old enough to study rhetoric and logic. Of these writers on the teaching of Latin, the most eminent were Sturm, Erasmus, Melanchthon, Lubinus, Vossius, Sanctius (the author of the Minerva), Ritter, Helvicus, Bodinus, Valentinus Andreæ, and, among Frenchmen, Coecilius Frey. Nor were Ascham and Mulcaster in England the least significant of the critics of method. Comenius was acquainted with almost all previous writers on education, except probably Ascham and Mulcaster, to whom he never alludes. He read everything that he could hear of with a view to find a method, and he does not appear ever to have been desirous to supersede the work of others. If he had found what he wanted, he would, we believe, have promulgated it, and advocated it as a loyal pupil. That he owed much to the previous writers is certain; but the prime characteristic of his work on Latin was his own. Especially does he introduce a new epoch in education, by constructing a general methodology which should go beyond mere Latin, and be equally applicable to all subjects of instruction.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.