Meanwhile his great didactic treatise, which had been written in his native Czech tongue, was yet unpublished.

Continuing Comenius Modernizes Education,

our selection from John Amos Comenius – Bishop of the Moravians, His Life and Educational Works by Simon Somerville Laurie published in 1892. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Comenius Modernizes Education.

Time: 1638

Place: Prague

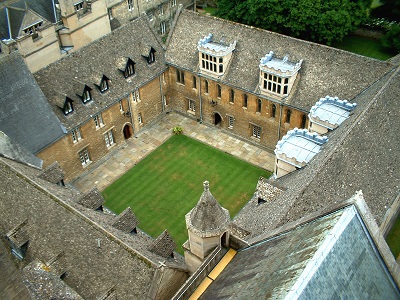

CC BY-SA 2.5 image from Wikipedia.

Before bringing his thoughts into definite shape, he wrote to all the distinguished men to whom he could obtain access. He addressed Ratich, among others, but received no answer; many of his letters also were returned, because the persons addressed could not be found. Valentinus Andreæ wrote to him in encouraging terms, saying that he gladly passed on the torch to him. His mind became now much agitated by the importance of the question and by the excitement of discovery. He saw his whole scheme assuming shape under his pen, and was filled, like other zealous men, before and since, with the highest hopes of the benefits which he would confer on the whole human race by his discoveries. He resolved to call his treatise Didactica Magna, or Omnes omnia docendi Artificium. He found a consolation for his misfortunes in the work of invention, and even saw the hand of Providence in the coincidence of the overthrow of schools, through persecutions and wars, and those ideas of a new method which had been vouchsafed to him, and which he was elaborating. Everything might now be begun anew, and untrammelled by the errors and prejudices of the past.

Some scruples as to a theologian and pastor being so entirely preoccupied with educational questions he had, however, to overcome. “Suffer, I pray, Christian friends, that I speak confidentially with you for a moment. Those who know me intimately know that I am a man of moderate ability and of almost no learning, but one who, bewailing the evils of his time, is eager to remedy them, if this in any be granted me to do, either by my own discoveries or by those of another — none of which things can come save from a gracious God. If, then, anything be here found well done, it is not mine, but his, who from the mouths of babes and sucklings hath perfected praise, and who, that he may in verity show himself faithful, true, and gracious, gives to those who ask, opens to those who knock, and offers to those who seek. Christ my Lord knows that my heart is so simple that it matters not to me whether I teach or be taught, act the part of teacher of teachers or disciple of disciples. What the Lord has given me I send forth for the common good.” His deepest conviction was that the sole hope of healing the dissensions of both church and state lay in the proper education of youth.

When he had completed his Great Didactic, he did not publish it, for he was still hoping to be restored to his native Moravia, where he proposed to execute all his philanthropic schemes; indeed, the treatise was first written in his native Slav or Czech tongue. In 1632 there was convened a synod of the Moravian Brethren at Lissa, at which Comenius, now forty years of age, was elected to succeed his father-in-law, Cyrillus, as bishop of the scattered brethren — a position which enabled him to be of great service, by means of correspondence, to the members of the community, who were dispersed in various parts of Europe. Throughout the whole of his long life he continued this fatherly charge, and seemed never quite to abandon the hope of being restored, along with his fellow-exiles, to his native land — a hope doomed to disappointment. In his capacity of pastor-bishop he wrote several treatises, such as a History of the Persecutions of the Brotherhood, an account of the Moravian Church discipline and order, and polemical tracts against a contemporary Socinian.

Meanwhile his great didactic treatise, which had been written in his native Czech tongue, was yet unpublished. He was, it would appear, stimulated to the publication of it by an invitation he received in 1638, from the authorities in Sweden, to visit their country and undertake the reformation of their schools. He replied that he was unwilling to undertake a task at once so onerous and so invidious, but that he would gladly give the benefit of his advice to anyone of their own nation whom they might select for the duty. These communications led him to resume his labor on the Great Didactic, and to translate it into Latin, in which form it finally appeared.

Humanism, which had practically failed in the school, had, apart from this fact, no attractions for Comenius, and still less had the worldly wisdom of Montaigne. He was a leading Protestant theologian — a pastor and bishop of a small but earnest and devoted sect — and it was as such that he wrote on education. The best results of humanism could, after all, be only culture, and this not necessarily accompanied by moral earnestness or personal piety: on the contrary, probably dissociated from these, and leaning rather to scepticism and intellectual self-indulgence.

At the same time it must be noted that he never fairly faced the humanistic question; he rather gave it the cold shoulder from the first. His whole nature pointed in another direction. When he has to speak of the great instruments of humanistic education — ancient classical writers — he exhibits great distrust of them, and, if he does not banish them from the school altogether, it is simply because the higher instruction in the Latin and Greek tongues is seen to be impossible without them. Even in the universities, as his pansophic scheme shows, he would have Plato and Aristotle taught chiefly by means of analyses and epitomes. It might be urged in opposition to this view of the anti-humanism of Comenius, that he contemplated the acquisition of a good style in Latin in the higher stages of instruction: true, but in so far as he did so, it was merely with a practical aim — the more effective, and, if need be, oratorical, enforcement of moral and religious truth. The beauties and subtleties of artistic expression had little charm for him, nor did he set much store by the graces. The most conspicuous illustration of the absence of all idea of art in Comenius is to be found in his school drama. The unprofitable dreariness of that production would make a reader sick were he not relieved by a feeling of its absurdity.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.