Today’s installment concludes Comenius Modernizes Education,

our selection from John Amos Comenius – Bishop of the Moravians, His Life and Educational Works by Simon Somerville Laurie published in 1892.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Comenius Modernizes Education.

Time: 1638

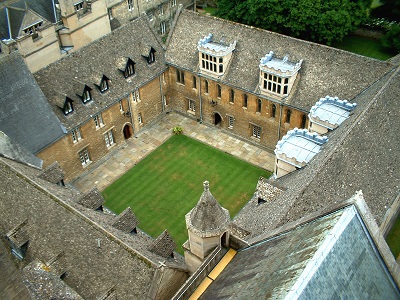

Place: Prague

CC BY-SA 2.5 image from Wikipedia.

It is in the department of method, however, that we recognize the chief contribution of Comenius to education. The mere attempt to systematize was a great advance. In seeking, however, for foundations on which to erect a coherent system, he had had to content himself with first principles which were vague and unscientific.

Modern psychology was in its infancy, and Comenius had little more than the generalizations of Plato and Aristotle, and those not strictly investigated by him, for his guide. In training to virtue, moral truth and the various moralities were assumed as if they emerged full-blown in the consciousness of man. In training to godliness, again, Christian dogma was ready to his hand. In the department of knowledge, that is to say, knowledge of the outer world, Comenius rested his method on the scholastic maxim, “Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius fuerit in sensu.” This maxim he enriched with the Baconian induction, comprehended by him, however, only in a general way. It was chiefly, however, the imagined harmony of physical and mental process that yielded his method. He believed that the process of the growth of external things had a close resemblance to the growth of the mind. Had he lived in these days he would doubtless have endeavored to work out the details of his method on a purely psychological basis; but in the then state of psychology he had to find another thread through the labyrinth. The mode of demonstration which he adopted was thus, as he himself called it, the syncretic or analogical. Whatever may be said of the harmony that exists between the growth of nature and of mind, there can be no doubt that the observation of the former is capable of suggesting, if it does not furnish, many of the rules of educational method.

From the simple to the complex, from the particular to the general, the concrete before the abstract, and all, step by step, and even by insensible degrees — these were among his leading principles of method. But the most important of all his principles was derived from the scholastic maxim quoted above. As all is from sense, let the thing to be known be itself presented to the senses, and let every sense be engaged in the perception of it. When it is impossible, from the nature of the case, to present the object itself, place a vivid picture of it before the pupil. The mere enumeration of these few principles, even if we drop out of view all his other contributions to method and school-management, will satisfy any man familiar with all the more recent treatises on education, that Comenius, even after giving his precursors their due, is to be regarded as the true founder of modern method, and that he anticipates Pestalozzi and all of the same school.

When we come to consider Comenius’ method as applied specially to language, we recognize its general truth, and the teachers of Europe and America will now be prepared to pay it the homage of theoretical approval at least. To admire, however, his own attempt at working out his linguistic method is impossible, unless we first accept his encyclopaedism. The very faults with which he charged the school practices of the time are simply repeated by himself in a new form. The boy’s mind is overloaded with a mass of words — the name and qualities of everything in heaven, on the earth, and under the earth. It was impossible that all these things, or even pictures of them, could be presented to sense, and hence his books must have inflicted a heavy burden on the merely verbal memory of boys. We want children to grow into knowledge, not to swallow numberless facts made up into boluses. Again, the amount that was to be acquired within a given time was beyond the youthful capacity. Any teacher will satisfy himself of this who will simply count the words and sentences in the Janua and Orbis of Comenius, and then try to distribute these over the schooltime allowed them. Like all reformers, Comenius was oversanguine. I do not overlook the fact that command over the Latin tongue as a vehicle of expression was necessary to those who meant to devote themselves to professions and to learning, and that Comenius had his justification for introducing a mass of vocables now wholly useless to the student of Latin. But even for his own time, Comenius, under the influence of his encyclopaedic passion, overdid his task. His real merits in language-teaching lie in the introduction of the principle of graduated reading-books, in the simplification of Latin grammar, in his founding instruction in foreign tongues on the vernacular, and in his insisting on method in instruction. But these were great merits, too soon forgotten by the dull race of schoolmasters, if, indeed, they were ever fully recognized by them till quite recent times.

Finally, Comenius’ views as to the inner organization of a school were original, and have proved themselves in all essential respects correct.

The same may be said of his scheme for the organization of a state system — a scheme which is substantially, mutatis mutandis, at this moment embodied in the highly developed system of Germany.

When we consider, then, that Comenius first formally and fully developed educational method, that he introduced important reforms into the teaching of languages, that he introduced into schools the study of nature, that he advocated with intelligence, and not on purely sentimental grounds, a milder discipline, we are justified in assigning to him a high, if not the highest, place among modern educational writers. The voluminousness of his treatises, their prolixity, their repetitions, and their defects of styles have all operated to prevent men studying him. The substance of what he has written has been, I believe, faithfully given by me, but it has not been possible to transfer to these pages the fervor, the glow, and the pious aspirations of the good old bishop.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Comenius Modernizes Education by Simon Somerville Laurie from his book John Amos Comenius – Bishop of the Moravians, His Life and Educational Works published in 1892. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Comenius Modernizes Education here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.