This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Looking for an Education Methodology.

Introduction

John Amos Comenius (1592-1671) is now generally recognized as the founder of modern education. Just what his work has been is best left to Mr. Laurie, the leading authority upon his life. What the schools were before his time is almost too dreary a picture to attempt to draw. Everything was hopelessly haphazard, almost hopelessly uninteresting. Only in the schools of the Jesuits was anything approaching skill employed to stimulate the learner. If a child did not advance, the teacher held himself no way responsible. The lad was adjudged a dullard and left to remain in his stupidity with the rest of the blockhead world.

The chief work of Comenius, the Didactica Magna, was probably finished about 1638, and was shown in manuscript to many persons at that time. Its ideas as to education were widely accepted, and its influence and that of its author spread rapidly over much of Europe. The publication of his works was delayed until 1657.

This selection is from John Amos Comenius – Bishop of the Moravians, His Life and Educational Works by Simon Somerville Laurie published in 1881. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Simon Somerville Laurie was Bell Professor of Education at Edinburgh University who wrote extensively on the philosophy of education.

Time: 1638

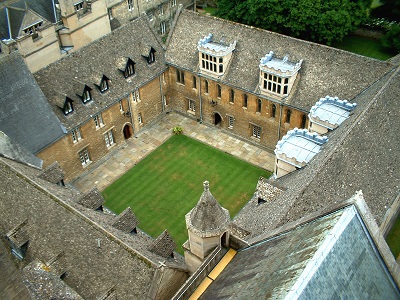

Place: Prague

CC BY-SA 2.5 image from Wikipedia.

In the history of education it is important to recognize the existence of the two parallel streams of intellectual and spiritual regeneration. The leaders of both, like the leaders of all great social changes, at once bethought themselves of the schools. Their hope was in the young, and hence the reform of education early engaged their attention.

The improvements made in the grammar-schools under the influence of Melanchthon and Sturm, and in England of Colet and Ascham, did not endure, save in a very limited sense. Pure classical literature was now read — a great gain certainly, but this was all. There was no tradition of method, as was the case in the Jesuit order. During the latter half of the sixteenth century, the complaints made of the state of the schools, the waste of time, the barbarous and intricate grammar rules, the cruel discipline, were loud and long, and proceeded from men of the highest intellectual standing. To unity in the Reformed churches they looked, but looked in vain, for a settlement of opinion, and to the school they looked as the sole hope of the future. The school, as it actually existed, might have well filled them with despair.

Even in the universities Aristotelian physics and metaphysics, and with them the scholastic philosophy, still held their own. The reforms initiated mainly by Melanchthon had not, indeed, contemplated the overthrow of Aristotelianism. He and the other humanists merely desired to substitute Aristotle himself in the original for the Latin translation from the Arabic, necessarily misleading, and the Greek and Latin classics for barbarous epitomes. These very reforms, however, perpetuated the reign of Aristotle, when the spirit that actuated the Reformers was dead, and there had been a relapse into the old scholasticism. The Jesuit reaction, also, which recovered France and South Germany for the papal see, was powerful enough to preserve a footing for the metaphysical theology of St. Thomas Aquinas and the schoolmen. In England, Milton was of opinion that the youth of the universities were, even so late as his time, still presented with an “asinine feast of sow-thistles.” These retrogressions in school and university serve to show how exceedingly difficult it is to contrive any system of education, middle or upper, which will work itself when the contrivers pass from the scene. Hence the importance, it seems to us, of having in every university, as part of the philosophical faculty, a department for the exposition of this very question of education — surely a very important subject in itself as an academic study, and in its practical relations transcending perhaps all others. How are the best traditions of educational theory and practice to be preserved and handed down if those who are to instruct the youth of the country are to be sent forth to their work from our universities with minds absolutely vacant as to the principles and history of their profession — if they have never been taught to ask themselves the question, “What am I going to do?” “Why?” and “How?” This subject is one worthy of consideration both by the universities and the state. It was the want of method that led to the decline of schools after the Reformation period; it was the study of method which gave the Jesuits the superiority that on many parts of the Continent they still retain.

In 1605 there appeared a book which was destined to place educational method on a scientific foundation, although its mission is not yet, it is true, accomplished. This was Francis Bacon’s Advancement of Learning, which was followed some years later by the Organum. For some time the thoughts of men had been turning to the study of nature. Bacon represented this movement, and gave it the necessary impulse by his masterly survey of the domain of human knowledge, his pregnant suggestions, and his formulation of scientific method. Bacon was not aware of his relations to the science and art of education; he praises the Jesuit schools, not knowing that he was subverting their very foundations. We know inductively: that was the sum of Bacon’s teaching. In the sphere of outer nature, the scholastic saying, “Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius fuerit in sensu,” was accepted, but with this addition, that the impressions on our senses were not themselves to be trusted. The mode of verifying sense-impressions, and the grounds of valid and necessary inference, had to be investigated and applied. It is manifest that if we can tell how it is we know, it follows that the method of intellectual instruction is scientifically settled.

But Bacon not only represented the urgent longing for a coördination of the sciences and for a new method, he also represented the weariness of words, phrases, and vain subtleties which had been gradually growing in strength since the time of Montaigne, Ludovicus Vives, and Erasmus. The poets, also, had been placing nature before the minds of men in a new aspect. The humanists, as we have said, while unquestionably improving the aims and procedure of education, had been powerless to prevent the tendency to fall once more under the dominion of words, and to revert to mere form. The realism of human life and thought, which constituted their raison d’être, had been unable to sustain itself as a principle of action, because there was no school of method. It was the study of the realities of sense that was finally to place education on a scientific basis, and make reaction, as to method at least, impossible.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.