This series has four easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Francis Xavier Arrives in Japan.

Introduction

Christianity was hardly the only religion introduced into Japan but it was the only one that came in together with foreign and domestic threats. of foreign conquest.

Lands discovered or settled by Europeans after the founding of the Jesuits were quickly chosen by the zealous members of that order as scenes of missionary work. In the case of Japan, missions followed discovery with unusual rapidity.

Excepting what was told by Marco Polo, who visited the coast of Japan in the thirteenth century, nothing was learned of that country by the Western World until its discovery by the Portuguese. In 1541 King John III requested Francis Xavier, one of the Jesuit founders, with other members of his order, to undertake missionary work in the Portuguese colonies. Through his labors in India, Xavier became known as the “Apostle of the Indies.” Before sailing to Japan he had established a flourishing mission with a school, called the Seminary of the Holy Faith, at Goa, on the Malabar coast of India.

This selection is from Review of the Introduction of Christianity into China and Japan in Asiatic Society Transactions, Volume VI by John H. Gubbins published in 1878. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

John Harington Gubbins (1852-1929) was a British linguist, consular official and diplomat. In this account take special note of the large numbers of converts. The rapid expansion and contraction makes this story exceptional in religious history.

Time: 1549

Place: Japan

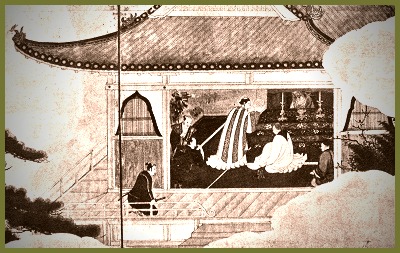

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It was to Portuguese enterprise that Christianity owed its introduction into Japan in the sixteenth century. As early as 1542 Portuguese trading vessels began to visit Japan, where they exchanged Western commodities for the then little-known products of the Japanese islands; and seven years afterward three Portuguese missionaries (Xavier, Torres, and Fernandez) took passage in one of these merchant ships and landed at Kagoshima.

The leading spirit of the three, it need scarcely be said, was Xavier, who had already acquired considerable reputation by his missionary labors in India. After a short residence the missionaries were forced to leave Satsuma, and after as short a stay in the island of Hirado, which appears to have been then the rendezvous of trade between the Portuguese merchants and the Japanese, they crossed over to the mainland and settled down in Yamaguchi in Nagato, the chief town of the territories of the Prince of Choshiu. After a visit to the capital, which was productive of no result, owing to the disturbed state of the country, Xavier (November, 1551) left Japan with the intention of founding a Jesuit mission in China, but died on his way in the island of Sancian.

In 1553 fresh missionaries arrived, some of whom remained in Bungo, where Xavier had made a favorable impression before his departure, while others joined their fellow-missionaries in Yamaguchi. After having been driven from the latter place by the outbreak of disturbances, and having failed to establish a footing in Hizen, we find the missionaries in 1557 collected in Bungo, and this province appears to have become their headquarters from that time. In the course of the next year but one, Vilela made a visit to Kioto, Sakai, and other places, during which he is said to have gained a convert in the person of the daimio, of the small principality of Omura, who displayed an imprudent excess of religious zeal in the destruction of idols and other extreme measures, which could only tend to provoke the hostility of the Buddhist priesthood. The conversion of this prince was followed by that of Arima-no-Kami (mistakenly called the Prince of Arima by the Jesuits).

Other missionaries arriving in 1560, the circle of operations was extended; but shortly afterward the revolution, headed by Mori, compelled Vilela to leave Kioto, where he had settled, and a simultaneous outbreak in Omura necessitated the withdrawal of the missionaries stationed there. Mori, of Choshiu, was perhaps the most powerful noble of the day, possessing no fewer than ten provinces, and, as he was throughout an open enemy to Christianity, his influence was exercised against it with much ill result.

On Vilela’s return to Kioto from Sakai, where a branch mission had been established, he succeeded in gaining several distinguished converts. Among these were Takayama, a leading general of the time, and his nephew. He did not, however, remain long in the capital. The recurrence of troubles in 1568 made it necessary for him to withdraw, and he then proceeded to Nagasaki, where he met with considerable success. In this same year we come across Valegnani preaching in the Goto Isles, and Torres in the island of Seki, where he died. Almeida, too, about this time founded a Christian community at Shimabara, afterward notorious as the scene of the revolt and massacre of the Christians.

Hitherto we find little mention of Christianity in Japanese books. This may partly be explained by the fact that the labors of the missionaries were chiefly confined to the southern provinces, Christianity having as yet made little progress at Kioto, the seat of literature. But the scarcity of Japanese records can scarcely be wondered at in the face of the edict issued later in the next century, which interdicted not only books on the subject of Christianity, but any book in which even the name of Christian or the word Foreign should be mentioned.

Short notices occur in several native works of the arrival in Kioto at this date of the Jesuit missionary Organtin, and some curious details are furnished respecting the progress of Christianity in the capital and the attitude of Nobunaga in regard to it.

The Saikoku Kirishitan Bateren Jitsu Roku, or “True Record of Christian Padres in Kiushiu,” gives a minute account of the appearance and dress of Organtin, and goes on to say: “He was asked his name and why he had come to Japan, and replied that he was the Padre Organtin and had come to spread his religion. He was told that he could not be allowed at once to preach his religion, but would be informed later on. Nobunaga accordingly took counsel with his retainers as to whether he should allow Christianity to be preached or not. One of these strongly advised him not to do so, on the ground that there were already enough religions in the country. But Nobunaga replied that Buddhism had been introduced from abroad and had done good in the country, and he therefore did not see why Christianity should not be granted a trial. Organtin was consequently allowed to erect a church and to send for others of his order, who, when they came, were found to be like him in appearance. Their plan of action was to tend the sick and relieve the poor, and so prepare the way for the reception of Christianity, and then to convert everyone and make the sixty-six provinces of Japan subject to Portugal.”

The Ibuki Mogusa gives further details of this subject, and says that the Jesuits called their church Yierokuji, after the name of the period in which it was built, but that Nobunaga changed the name to Nambanji, or “Temple of the Southern Savages.” The word Namban was the term usually applied to the Portuguese and Spaniards.

During the next ten years Organtin and other missionaries worked with considerable success in Kioto under Nobunaga’s immediate protection. This period is also remarkable for the conversion of the Prince of Bungo, who made open profession of Christianity and retired into private life, and for the rapid progress which the new doctrine made among the subjects of Arima-no-Kami. This good fortune was again counterbalanced by the course of events in the Goto Islands, where Christianity lost much ground owing to a change of rulers.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.