The King had other things to do at that moment than assent to a bill for an assembly of divines. He was at York, gathering his forces for the civil war; and by the time when it was expected the assembly should have been at work the civil war had begun.

Continuing Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England,

our selection from Life of John Milton by David Masson published in 1880. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England.

Time: 1643

Place: Westminister

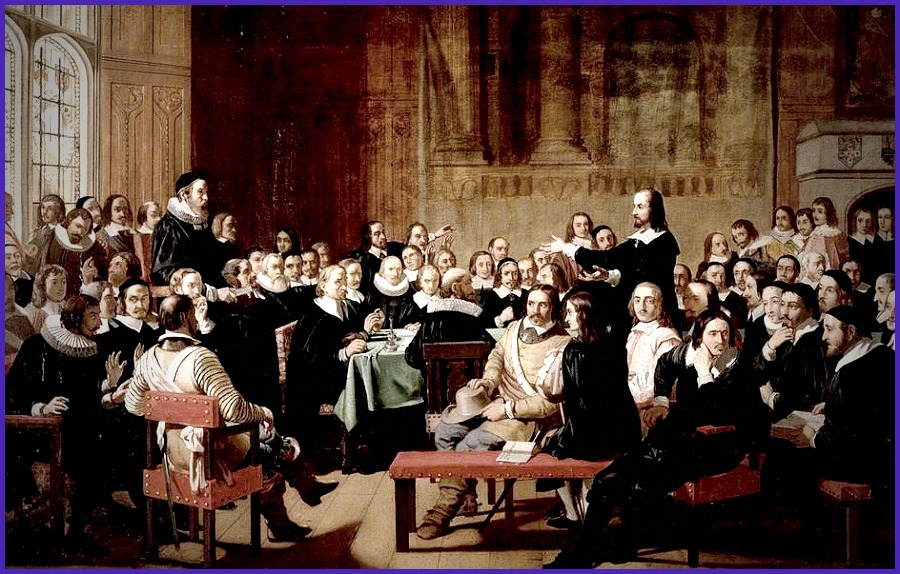

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In almost all cases the divines named by the knights and burgesses for their several counties were approved of by the House unanimously; but a vote was taken on the eligibility of one of the divines named for Yorkshire, and he was carried by a bare majority of one hundred three to ninety-nine, and exceptions having been taken on the 25th to the two appointed for Cumberland on the 20th, their appointment was cancelled and others were substituted. On the same day on which the list of divines was completed, a committee of twenty-seven members of the House, including Hampden, Selden, and Lord Falkland, was appointed “to consider of the readiest way to put in execution the resolutions of this House in consulting with such divines as they have named.” The result was that on May 9th there was brought in a “bill for calling an assembly of godly and learned divines to be consulted with by the Parliament, for the settling of the government and liturgy of the Church, and for the vindicating and clearing of the doctrine of the Church of England from false aspersions and interpretations.” On that day the bill was read twice in the Commons and committed; and on the 19th it was read a third time and passed. The Lords, having then taken the bill into consideration, proposed (May 26, 1642) the addition of fourteen divines of their own choice to those named by the Commons; and, the Commons having agreed to this amendment, the bill passed both Houses, June 1st, and waited only the King’s assent. It was intended that the assembly should meet the next month.

The King had other things to do at that moment than assent to a bill for an assembly of divines. He was at York, gathering his forces for the civil war; and by the time when it was expected the assembly should have been at work the civil war had begun. Nevertheless, the Parliament persevered in their design. Twice again, while the war was in its first stage, bills were introduced to the same effect as that which had been stopped. Bill the second for calling an assembly of divines was in October, and bill the third in December, 1642. In these bills the two houses kept to the one hundred sixteen divines agreed upon under the first bill, with — as far as I have been able to trace the matter through their journals — only one deletion, two substitutions, and three proposed additions.

Still, by the stress of the war, the assembly was postponed. At last, hopeless of a bill that should pass in the regular way by the King’s consent, the houses resorted, in this as in other things, to their peremptory plan of ordinance by their own authority. On May 13, 1643, an ordinance for calling an assembly was introduced in the Commons; which ordinance, after due going and coming between the two Houses, came to maturity June 12th, when it was entered at full length in the Lords Journals. “Whereas, among the infinite blessings of Almighty God upon this nation” — so runs the preamble of the ordinance — “none is, or can be, more dear to us than the purity of our religion; and forasmuch as many things yet remain in the discipline, liturgy, and government of the Church which necessarily require a more perfect reformation: and whereas it has been declared and resolved, by the Lords and Commons assembled in parliament, that the present church government by archbishops, bishops, their chancellors, commissaries, deans, deans and chapters, arch-deacons, and other ecclesiastical officers depending on the hierarchy, is evil, and justly offensive and burdensome to the kingdom, and a great impediment to reformation and growth of religion, and very prejudicial to the state and government of this kingdom, and that therefore they are resolved the same shall be taken away, and that such a government shall be settled in the Church as may be agreeable to God’s Holy Word, and most apt to procure and preserve the peace of the Church at home, and nearer agreement with the Church of Scotland, and other reformed churches abroad. Be it therefore ordained,” etc.

What is ordained is that one hundred forty-nine persons, enumerated by name in the ordinance — ten of them being members of the Lords House, twenty members of the Commons House, and the other one hundred nineteen mainly the divines that had already been fixed upon, most of them a year before — shall meet on July 1st next in King Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster; and that these persons, and such others as shall be added to them by Parliament from time to time, shall have power to continue their sittings as long as Parliament may see fit, and “to confer and treat among themselves of such matters and things concerning the liturgy, discipline, and government of the Church of England, or the vindicating and clearing of the doctrine of the same from all false aspersions and misconstructions, as shall be proposed by either or both houses of Parliament, and no other.” The words in Italics are important. The assembly was not to be an independent national council ranging at its will and settling things by its own authority. It was to be a body advising Parliament on matters referred to it, and on these alone, and its conclusions were to have no validity until they should be reported to Parliament and confirmed there.

Forty members of the assembly were to constitute a quorum, and the proceedings were not to be divulged without consent of Parliament. Four shillings a day were to be allowed to each clerical member for his expenses, with immunity for non-residence in his parish or any neglect of his ordinary duties that might be entailed by his presence at Westminster. William Twisse, D.D., of Newbury, was to be prolocutor, or chairman, of the assembly; and he was to have two “assessors,” to supply his place in case of necessary absence. There were to be two “scribes,” who should be divines, but not members of the assembly, to take minutes of the proceedings.

Every member of the assembly, on his first entrance, was to make solemn protestation that he would not maintain anything but what he believed to be the truth; no resolution on any question was to be come to on the same day on which it was first propounded; whatever any speaker maintained to be necessary he was to prove out of the Scriptures; all decisions of the major part of the assembly were to be reported to Parliament as the decisions of the assembly; but the dissents of individual members were to be duly registered, if they required it, and also reported to Parliament. The Lords wanted to regulate also that no long speeches should be permitted in the assembly, so that matters might not be carried by “impertinent flourishes”; but the Commons, for reasons that are not far to seek, did not agree to this regulation.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.