The number of Christians in Japan at this time is stated to have been one million eight hundred thousand.

Continuing Christianity Introduced Into Japan,

our selection from Review of the Introduction of Christianity into China and Japan in Asiatic Society Transactions, Volume VI by John H. Gubbins published in 1878. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Christianity Introduced Into Japan.

Time: 1614

Place: Japan

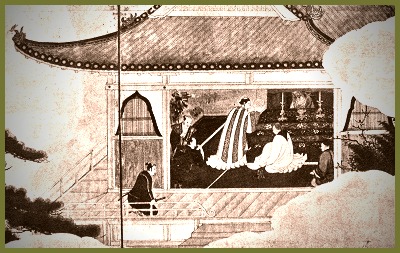

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Hitherto, for a period of forty-four years, the Jesuits had it all their own way in Japan; latterly, by virtue of a bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII in 1585 — the date of the appointment of the first bishop and of the arrival at Rome of the Japanese mission — and subsequently confirmed by the bull of Clement III in 1600, by which the religieux of other orders were excluded from missionary work in Japan. The object of these papal decrees was, it seems, to insure the propagation of Christianity on a uniform system. They were, however, disregarded when the time came, and therefore, for a new influence which was brought to bear upon Christianity at this date — not altogether for its good, if the Jesuit accounts may be credited — we must look to the arrival of an embassy from the Governor of the Philippines, whose ambassador was accompanied by four Franciscan priests.

These new arrivals, when confronted by the Jesuits with the papal bull, declared that they had not transgressed it, and defended their action on the ground that they had come attached to an embassy and not in the character of missionaries; but they argued at the same time, with a casuistry only equaled by their opponents, that, having once arrived in Japan, there was nothing to hinder them from exercising their calling as preachers of Christianity.

The embassy was successful, and Baptiste, who appears to have conducted the negotiations in place of the real envoy, obtained Hideyoshi’s consent to his shrewd proposal that, pending the reference to Manila of Hideyoshi’s claim to the sovereignty of the Philippines, he and his brother missionaries should remain as hostages. Hideyoshi, while consenting, made their residence conditional on their not preaching Christianity — a condition which it is needless to say was never observed.

Thus, at one and the same time, the Spaniards, who had long been watching with their jealous eyes the exclusive right of trade enjoyed by the Portuguese, obtained an opening for commerce, and the Franciscans a footing for their religious mission.

It was not long before the newly-arrived missionaries were called upon to prove their devotion to their cause. In 1593, in consequence of the indiscreet statements of the pilot of a Spanish galleon, which, being driven by stress of weather into a port of Tosa, was seized by Hideyoshi, nine missionaries — namely, six Franciscans and three Jesuits — were arrested in Kioto and Osaka, and, having been taken to Nagasaki, were there burned. This was the first execution carried out by the government.

Hideyoshi died in the following year (1594), and the civil troubles which preceded the succession of Iyeyasu to the post of administrator, in which the Christians lost their chief supporter, Konishi, who took part against Iyeyasu, favored the progress of Christianity in so far as diverting attention from it to matters of more pressing moment.

Iyeyasu’s policy toward Christianity was a repetition of his predecessor’s. Occupied entirely with military campaigns against those who refused to acknowledge his supremacy, he permitted the Jesuits, who now numbered one hundred, to establish themselves in force at Kioto, Osaka, and Nagasaki. But as soon as tranquility was restored, and he felt himself secure in the seat of power, he at once gave proof of the policy he intended to follow by the issue of a decree of expulsion against the missionaries. This was in 1600. The Jesuit writers affirm that he was induced to withdraw his edict in consequence of the threatening attitude adopted by certain Christian nobles who had espoused his cause in the late civil war, but no mention is made of this in the Japanese accounts.

So varying, and indeed so altogether unintelligible, was the action of the different nobles throughout Kiushiu in regard to Christianity during the next few years, that we see one who was not a Christian offering an asylum in his dominions to several hundred native converts who were expelled from a neighboring province; another who had systematically opposed the introduction of Christianity actually sending a mission to the Philippines to ask for missionaries; while a third, who had hitherto made himself conspicuous by his almost fanatical zeal in the Christian cause, suddenly abandoned his new faith, and, from having been one of its most ardent supporters, became one of its most bitter foes.

The year 1602 is remarkable for the dispatch of an embassy by Iyeyasu to the Philippines, and for the large number of religieux of all orders who flocked to Japan.

Affairs remained in statu quo for the next two or three years, during which the Christian cause was weakened by the death of two men which it could ill afford to lose. One of these was the noble called Kondera by Charlevoix, but whose name we have been unable to trace in Japanese records. The other was Organtin, who had deservedly the reputation of being the most energetic member of the Jesuit body.

The number of Christians in Japan at this time is stated to have been one million eight hundred thousand. The number of missionaries was of course proportionally large, and was increased by the issue in 1608 of a new bull by Pope Paul V allowing to relligieux of all orders free access to Japan.

The year 1610 is remarkable for the arrival of the Dutch, who settled in Hirado, and for the destruction in the harbor of Nagasaki of the annual Portuguese galleon sent by the traders of Macao. In this latter affair, which rose out of a dispute between the natives and the people of the ship, Arima-no-Kami was concerned, and his alliance with the missionaries was thus terminated.

In 1611 no less than three embassies arrived in Japan from the Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese respectively, and in 1613 Saris succeeded in founding an English factory in Hirado, where the Dutch had already established themselves. It was early in the following year that Christianity was finally proscribed by Iyeyasu. The decree of expulsion directed against the missionaries was followed by a fierce outbreak of persecution in all the provinces in which Christians were to be found, which was conducted with systematic and relentless severity.

The Jesuit accounts attribute this resolution on the part of Iyeyasu to the intrigues of the English and Dutch traders. Two stories, by one of which it was sought to fix the blame on the former and by the other on the latter, were circulated, and will be found at length in Charlevoix’s history.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.