Christianity was at its most flourishing stage during the first few years of Hideyoshi’s administration.

Continuing Christianity Introduced Into Japan,

our selection from Review of the Introduction of Christianity into China and Japan in Asiatic Society Transactions, Volume VI by John H. Gubbins published in 1878. The selection is presented in four easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Christianity Introduced Into Japan.

Time: 1582

Place: Japan

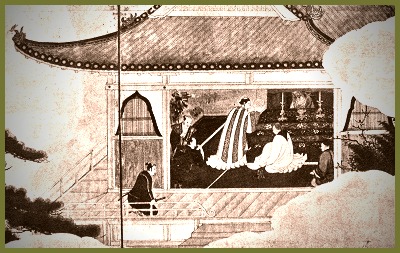

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Ten years thus passed away, when the Christian communities sustained great loss in the disgrace of Takayama, who was banished to Kaga for taking part in an unsuccessful intrigue against Nobunaga which was headed by the Prince of Choshiu. Takayama’s nephew, Ukon, however, declared for Nobunaga, and the latter gave a further proof of his friendly feeling toward Christianity by establishing a church in Adzuchi-no-Shiro, the castle town which he had built for himself in his native province of Omi.

In 1582 a mission was sent to the papal see on the part of the Princes of Bungo and Omura, and Arima-no-Kami. This mission was accompanied by Valegnani, and reached Rome in 1585, returning five years later to Japan.

In the following year Nobunaga was assassinated and Hideyoshi, who succeeded him in the chief power, was content, for the first three or four years of his administration, to follow in the line of policy marked out by his predecessor. Christianity, therefore, progressed in spite of the drawbacks caused by the frequent feuds between the southern daimios, and seminaries were established under Hideyoshi’s auspices at Osaka and Sakai. During this period Martinez arrived in the capacity of bishop; he was charged with costly presents from the Viceroy of Goa to Hideyoshi, and received a favorable audience.

Hideyoshi’s attitude toward Christianity at this time is easily explained. The powerful southern barons were not willing to accept him as Nobunaga’s successor without a struggle, and there were other reasons against the adoption of too hasty measures. Two of his generals, Kondera and Konishi Setsu-no-Kami, who afterward commanded the second division of the army sent against Corea, the Governor of Osaka, and numerous other officers of state and nobles of rank and influence, had embraced Christianity, and the Christians were therefore not without influential supporters. Hideyoshi’s first act was to secure his position. For this purpose he marched into Kiushiu at the head of a large force and was everywhere victorious. This done, he threw off the mask he had been wearing up to this time, and in 1587 took the first step in his new course of action by ordering the destruction of the Christian church at Kioto — which had been in existence for a period of eighteen years — and the expulsion of the missionaries from the capital.

It will be seen by the following extract from the Ibuki Mogusa that Nobunaga at one time entertained designs for the destruction of Nambanji.

“Nobunaga,” we read, “now began to regret his previous policy in permitting the introduction of Christianity. He accordingly assembled his retainers and said to them: ‘The conduct of these missionaries in persuading people to join them by giving money does not please me. It must be, I think, that they harbor the design of seizing the country. How would it be, think you, if we were to demolish Nambanji?’ To this Mayeda Tokuzenin replied: ‘It is now too late to demolish the temple of Nambanji. To endeavor to arrest the power of this religion now is like trying to arrest the current of the ocean. Nobles both great and small have become adherents of it. If you would exterminate this religion now, there is fear lest disturbances be created even among your own retainers. I am, therefore, of opinion that you should abandon your intention of destroying Nambanji.’ Nobunaga in consequence regretted exceedingly his previous action with regard to the Christian religion, and set about thinking how he could root it out.”

The Jesuit writers attribute Hideyoshi’s sudden change of attitude to three different causes, but it is clear that Hideyoshi was never favorable to Christianity, and that he only waited for his power to be secure before taking decided measures of hostility. His real feeling in regard to the Christians and their teachers is explained in the Life of Hideyoshi, from which work we learn that even before his accession to power he had ventured to remonstrate with Nobunaga for his policy toward Christianity.

Hideyoshi’s next act was to banish Takayama Ukon to Kaga, where his uncle already was, and he then in 1588 issued a decree ordering the missionaries to assemble at Hirado and prepare to leave Japan. They did so, but finding that measures were not pushed to extremity they dispersed and placed themselves under the protection of various nobles who had embraced Christianity. The territories of these princes offered safe asylums, and in these scattered districts the work of Christianity progressed secretly while openly interdicted.

In 1591 Valegnani had a favorable audience of Hideyoshi, but he was received entirely in an official capacity, namely, in the character of envoy of the Viceroy of Goa.

Christianity was at its most flourishing stage during the first few years of Hideyoshi’s administration. We can discern the existence at this date of a strong Christian party in the country, though the turning-point had been reached, and the tide of progress was on the ebb. It is to this influence probably, coupled with the fact that his many warlike expeditions left him little leisure to devote to religious questions, that we must attribute the slight relaxation observable in his policy toward Christianity at this time.

“Up to this date,” says Charlevoix, “Hideyoshi had not evinced any special bitterness against Christianity, and had not proceeded to rigorous measures in regard to Christians. The condition of Christianity was reassuring. Rodriguez was well in favor at court, and Organtin had returned to Kioto along with several other missionaries, and found means to render as much assistance to the Christians in that part of the country as he had been able to do before the issue of the edict against Christianity by Hideyoshi.”

The inference which it is intended should be drawn from these remarks, taken with the context, is clear; namely, that, had the Jesuits been left alone to prosecute the work of evangelizing Japan, the ultimate result might have been very different. However, this was not to be.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.