Today’s installment concludes Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England,

our selection from Life of John Milton by David Masson published in 1880.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England.

Time: July 1, 1643

Place: Westminister

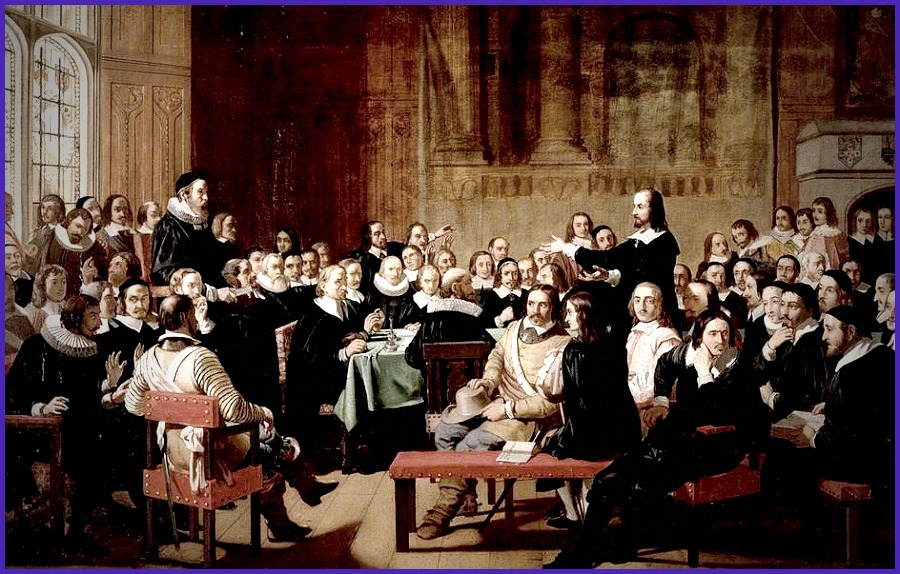

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Notwithstanding a royal proclamation from Oxford, dated June 22d, forbidding the assembly and threatening consequences, the first meeting duly took place on the day appointed — Saturday, July 1, 1643; and from that date till February 22, 1648-1649, or for more than five years and a half, the Westminster Assembly is to be borne in mind as a power of institution in the English realm, existing side by side with the Long Parliament, and in constant conference and cooperation with it. The number of its sittings during these five years and a half was one thousand one hundred sixty-three in all; which is at the rate of about four sittings every week for the whole time. The earliest years of the assembly were the most important. All in all, it was an assembly which left remarkable and permanent effects in the British islands, and the history of which ought to be more interesting, in some homely respects, to Britons now, than the history of the Council of Basel, the Council of Trent, or any other of the great ecclesiastical councils, more ancient and ecumenical, about which we hear so much.

Such was the famous Westminster Assembly, called together by the Parliament of England to consider the entire state of the country in matters of religion. The business intrusted to it was vast and complex. It was to revise and redefine the national creed, after its long lapse into so-called Arminianism and semi-popish error, and to advise also as to the new system of church government and the new forms of worship that should come in place of rejected episcopacy and the condemned liturgy. For it was still, be it remembered, the universal notion among English politicians that there must be a national church, and that no man, woman, or child within the land should be permitted to be out of the pale of that church. It was still the notion that it was possible to frame a certain number of propositions respecting God, heaven, angels, hell, devils, the creation of the universe, the soul of man, sin and its remedy, a life beyond death, and all the other most tremendous subjects of human contemplation, that should be absolutely true, or at least so just and sure a compendium of truth that the nation must be tied up to it, and it would be wrong to allow any man, woman, or child, subject to the law of England, to be astray from it in any item. This was the notion, and those one hundred forty-nine persons were appointed to frame the all-important propositions, or find them out by a due revision of the old articles, and to report to Parliament on that subject, as well as on the subjects of church organization and forms of worship.

The appointment, among the original one hundred forty-nine or one hundred fifty members of assembly, of such persons as Archbishop Usher, Bishops Brownrigge and Westfield, Featley, Hacket, Hammond, Holdsworth, Morley, Nicolson, Saunderson, and Samuel Ward — all of them defenders of an episcopacy of some kind — seems hardly reconcilable with the very terms of the ordinance calling the assembly. That ordinance implied that episcopacy was condemned and done with, and it convoked the assembly for the express purpose of considering, among other things, what should be put in its stead. It may have been thought, however, that it would impart a more liberal and eclectic character to the assembly to send a sprinkling of known Anglicans into it; or it may have been thought right to give some of the most respected of these an opportunity of retrieving themselves by acquiescing in what they could not prevent. As it chanced, however, the refusal of most of these to appear in the assembly at all, and the all but immediate dropping-off of the one or two who did appear at first, saved the assembly much trouble. It became thus a compact body, fit for its work, and in the main of one mind and way of thinking on some of the problems submitted to it.

In respect of theological doctrine, for example, the assembly, as it was then left, was practically unanimous. They were, almost to a man, Calvinists, or anti-Arminians, pledged by their antecedents to such a revision of the articles as should make the national creed more distinctly Calvinistic than before. Moreover, they were agreed as to their method for determining doctrine. It was to be the rigid application of the Protestant principle that the Bible is the sole rule of faith. The careful interpretation of Scripture — i.e., the collecting on any occasion of discussion of all the texts in the Old and New Testaments bearing on the point discussed, and the examination of these texts singly and in their connection and in the original tongues when necessary, so as to ascertain their exact sense — this was the understood rule with them all. Learning was, indeed, in demand, and the chief scholars, especially the chief Hebraists and rabbinists, of the assembly, were much looked up to: there might be references also to the fathers and to councils; no kind of historical lore but would be welcome: only all must subserve the one purpose of interpreting Scripture; and fathers, councils, and whatnot, could be cited, not as authorities, but only as witnesses. This understanding as to the determination of doctrine by the Bible alone, accompanied as it was by a nearly unanimous preconviction that it was the Calvinistic body of doctrines alone that could be reasoned out of the Bible, was to keep the assembly, I repeat, pretty much together from the first in matters of creed and theology. For perplexing questions as to the extent and limits of the inspiration of the Bible had not yet publicly arisen to invalidate the accepted method.

Footnote:

Alexander Henderson, the Scottish ecclesiastic and diplomat, was at this time most prominent among the Presbyterian leaders.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England by David Masson from his book Life of John Milton published in 1880. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.