This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Puritans and Presbyterians.

Introduction

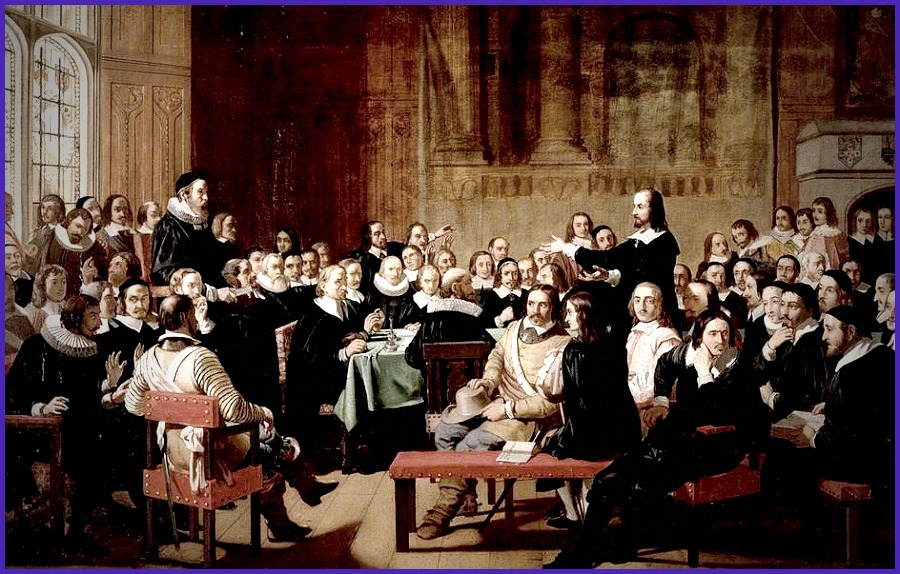

Official recognition of Presbyterianism in Great Britain marked a distinct departure in ecclesiastical affairs. The Westminster Assembly, whose confession and catechisms, while not accepted in England, became, and remained through the 20th. century, the doctrinal standards of the Scotch and American Presbyterian churches, was one of the most important religious convocations ever held. The Presbyterian form of church government has been adopted by various sects, whose representatives are found in many parts of the world.

The great object of the Westminster Assembly was to dictate dogmatically, articles of faith and a form of worship that should be compulsory. It was mainly owing to the influence of Oliver Cromwell, who stood for toleration and independence, within limits, that the assembly did not have its way.

This selection is from Life of John Milton by David Masson published in 1880.

Masson, the great authority on this subject, gives in the following pages a clear and comprehensive account of the religious situation in Great Britain at the time, of the composition of the assembly, and of its labors during the five years and more of its continuance.

Time: 1643

Place: Westminister

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

At the time of the meeting of the Westminster Assembly there was a tradition in the Puritan mind of England of two varieties of opinions as to the form of church government or discipline that should be substituted for episcopacy.

In the first place there was a tradition of the system of views known as Presbyterianism. From the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign, if not earlier, there had been Nonconformists who held that some form of the consistorial model which Calvin had set up in Geneva, and which Knox enlarged for Scotland, was the best for England, too. Thus Fuller, who dates the use of the term “Puritans,” as a nickname for the English Nonconformists generally, from the year 1564, and who goes on to say that within a few years after that date the chief of those to whom that term was first applied were either dead or very aged, adds: “Behold, another generation of active and zealous Nonconformists succeeded them: of these Coleman, Button, Halingham, and Benson (whose Christian names I cannot recover) were the chief; inveighing against the established church discipline, accounting everything from Rome that was not from Geneva, endeavoring in all things to conform the government of the English Church to the Presbyterian Reformation.”

Actually, in 1572, Fuller proceeds to tell us, a presbytery, the first in England, was set up at Wandsworth in Surrey; i.e., in that year a certain number of ministers of the Church of England organized themselves privately, without reference to bishops or other authorities, into a kind of presbyterial consistory, or classical court, for the management of the church business of their neighborhood. The heads of this Presbyterian movement, which gradually extended itself to London, were Mr. Field, lecturer at Wandsworth, Mr. Smith of Mitcham, Mr. Crane of Roehampton, Messrs. Wilcox, Standen, Jackson, Bonham, Saintloe, Travers, Charke, Barber, Gardiner, Crook, and Egerton; with whom were associated a good many laymen. A summary of their views on the subject of church government was drawn out in Latin, under the title Disciplina Ecclesiæ sacra ex Dei Verbo descripta, and, though it had to be printed at Geneva, became so well known that, according to Fuller, “Secundum usum Wandsworth was as much honored by some as secundum usum Sarum by others.”

The English Presbyterianism thus asserting itself and spreading found its ablest and most energetic leader in the famous Thomas Cartwright (1535-1603). No less by practical ingenuity than by the pen, he labored for presbytery; and under his direction Presbyterianism attained such dimensions that between 1580 and 1590 there were no fewer than five hundred beneficed clergymen of the Church of England, most of them Cambridge men, all pledged to general agreement in a revised form of the Wandsworth Directory of Discipline, all in private intercommunication among themselves, and all meeting occasionally, or at appointed times, in local conferences, or even in provincial and general synods. In addition to London, the parts of the country thus most leavened with Presbyterianism were the shires of Warwick, Northampton, Rutland, Leicester, Cambridge, and Essex.

Of course such an anomaly, of a Presbyterian organization of ministers existing within the body of the prelatic system established by law, and to the detriment or disintegration of that system, could not be tolerated; and, when Whitgift had procured sufficient information to enable him to seize and prosecute the chiefs, it was, in fact, stamped out. But the recollection of Cartwright and of Presbyterian principles remained in the English mind through the reigns of James and Charles, and characterized the main mass of the more effective and respectable Puritanism of those reigns. In other words, most of those Puritans, whether ministers or of the laity, who still continued members of the Church, only protesting against some of its rules and ceremonies, conjoined with this nonconformity in points of worship a dissatisfaction with the prelatic constitution of the Church, and a willingness to see the order of bishops removed, and the government of the Church remodelled on the Presbyterian system of parochial courts, classical or district meetings, provincial synods, and national assemblies.

During the supremacy of Laud, indeed, when any such wholesale revolution seemed hopeless, it is possible that English Puritanism within the Church had abandoned in some degree its dreamings over the Presbyterian theory, and had sunk, through exhaustion, into mere sighings after a relaxation of the established episcopacy. But the success of the Presbyterian revolt of the Scots in 1638, and their continued triumph in the two following years, had worked wonders. All the remains of native Presbyterian tradition in England had been kindled afresh, and new masses of English Puritan feeling, till then acquiescent in episcopacy, had been whirled into a passion for presbytery and nothing else. When the Long Parliament, at its first meeting (November, 1640), addressed itself to the question of a reform of the English Church, the force that beat against its doors most strongly from the outside world of English opinion consisted no longer of mere sighings after a limitation of episcopacy, but of a formed determination of myriads to have done with episcopacy root and branch, and to see a church government substituted somewhat after the Scottish pattern.

Two years more of discussion in and out of Parliament had vastly enlarged the dimensions of this revived and newly created English Presbyterianism. The passion for presbytery among the English laity had pervaded all the counties; and scores and hundreds of parish ministers who had kept as long as they could within the limits of mere Low-church Anglicanism, and had stood out, in their private reasonings, for the lawfulness and expediency of an order of officers in the Church superior to that of simple presbyters, if less lordly than the bishops, had been swept out of their scruples, and had joined themselves, even heartily, to the Presbyterian current. Thus, when the Westminster Assembly met (July, 1643), to consider, among other things, what form of church government the Parliament should be advised to establish in England in lieu of the episcopacy which it had been resolved to abolish, the injunction almost universally laid upon them by already formed opinion among the parliamentarians of England, whether laity or clergy out of the assembly, seemed to be that they should recommend conformity with Scottish presbytery. All the citizenship, all the respectability of London, for example, was resolutely Presbyterian, and of the one hundred twenty parish ministers of the city, surrounding the assembly, only three, so far as could be ascertained, were not of strict Presbyterian principles.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Valuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I’m shocked why this accident did not happened earlier! I bookmarked it.