The error of the Presbyterians, they maintained, retaining the synodical tyranny while they would throw off the prelatic.

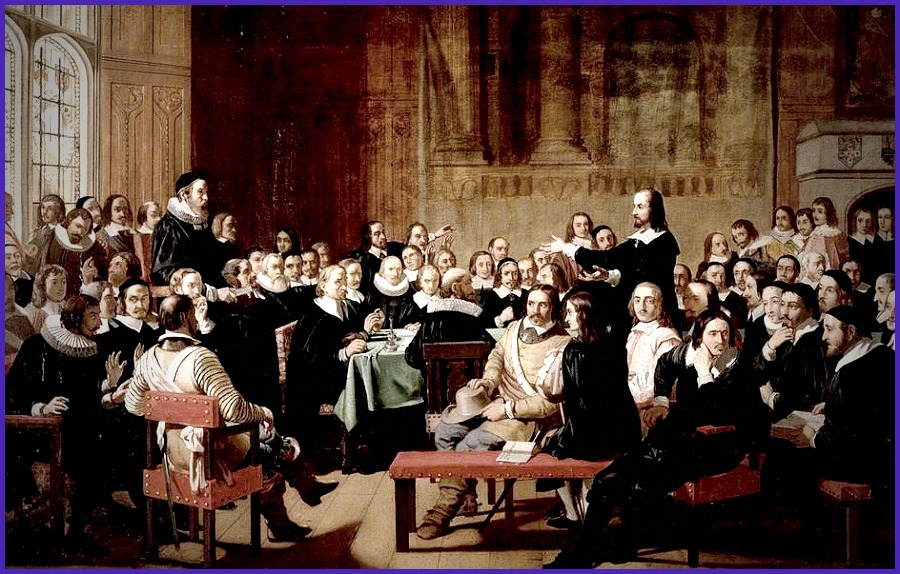

Continuing Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England,

our selection from Life of John Milton by David Masson published in 1880. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Westminister Assembly Establishes Presbyterianism in England.

Time: 1643

Place: Westminister

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Nevertheless, amid all this apparent prevalence of Presbyterianism, there was a stubborn tradition in England of another set of antiprelatic views, long stigmatized by the nickname of Brownism, but known latterly as Independency or Congregationalism.

Independents and Presbyterians are quite agreed in maintaining that the terms “bishop” or overseer, and “presbyter” or elder, were synonymous in the pure or primitive Church, and applied indifferently to the same persons, and that prelacy and all its developments were subsequent corruptions. The peculiar tenet of independency, distinguishing it from Presbyterianism, consists in something else. It consists in the belief that the only organization recognized in the primitive Church was that of the voluntary association of believers into local congregations, each choosing its own office-bearers and managing its own affairs, independently of neighboring congregations, though willing occasionally to hold friendly conferences with such neighboring congregations, and to profit by the collective advice. Gradually, it is asserted, this right or habit of occasional friendly conference between neighboring congregations had been mismanaged and abused, until the true independency of each voluntary society of Christians was forgotten, and authority came to be vested in synods or councils of the office-bearers of the churches of a district or province.

This usurpation of power by synods or councils, it is said, was as much a corruption of the primitive-church discipline as was prelacy itself, or the usurpation of power by eminent individual presbyters, assuming the name of “bishops” in a new sense. Nay, the one usurpation had prepared the way for the other; and, especially after the establishment of Christianity in the Roman Empire by the civil power, the two usurpations had gone on together, until the church became a vast political machinery of councils, smaller or larger, regulated by a hierarchy of bishops, archbishops, and patriarchs, all pointing to the popedom. The error of the Presbyterians, it is maintained, lies in their not perceiving this natural and historical connection of the two usurpations, and so retaining the synodical tyranny while they would throw off the prelatic.

Not having recovered the true original idea of an ecclesia as consisting simply of a society of individual Christians meeting together periodically and united by a voluntary compact, while the great invisible church of a nation or of the world consists of the whole multitude of such mutually independent societies harmoniously moved by the unseen Spirit present in all, Presbyterians, it is said, substitute the more mechanical image of a visible collective church for each community or nation, try to perfect that image by devices borrowed from civil polity, and find the perfection they seek in a system of national assemblies, provincial synods, and district courts of presbyters, superintending and controlling individual congregations. Independency, on the other hand, would purify the aggregate Church to the utmost, by throwing off the synodical tyranny as well as the prelatic, and restoring the complete power of discipline to each particular church or society of Christians formed in any one place.

So, I believe, though with varieties of expression, English Independents argue now. But, while they thus seek the original warrant for their views in the New Testament and in the practice of the primitive Church, and while they maintain also that the essence of these views was rightly revived in old English Wycliffism, and perhaps in some of the speculations which accompanied Luther’s Reformation on the Continent, they admit that the theory of Independency had to be worked out afresh by a new process of the English mind in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and they are content, I believe, that the crude, immediate beginning of that process should be sought in the opinions propagated, between 1580 and 1590, by the erratic Robert Brown, a Rutlandshire man, bred at Cambridge, who had become a preacher at Norwich.

Here and there in England by his tongue during those ten years, and sometimes by pamphlets in exile, Brown, who could boast that he had been “committed to thirty-two prisons, in some of which he could not see his hand at noon-day,” and who escaped the gallows only through some family connection he had with the all-powerful Lord Burghley, had preached doctrines far more violently schismatic than those of Cartwright and the majority of the Puritans. His attacks on bishops and episcopacy were boundlessly fierce; and the duty of separation in toto from the Church of England, the right of any number of persons to form themselves into a distinct congregation, the mutual independence of congregations so formed, and the liberty of any member of a congregation to preach or exhort in it, were among his leading tenets.

At length, tiring of the tempest he had raised around him, he accepted a living in Northamptonshire; and, though he is not known to have ever formally recanted any of his opinions, he lived on in his parsonage till as late as 1630, when Fuller knew him as a passionate and rather disreputable old man of eighty, employing a curate to do his work, quarrelling with everybody, and refusing to pay his rates. Meanwhile the opinions which he had propagated fifty years before had passed through a singular history in the minds and lives of men of steadier and more persevering character. For, though Brown himself had vanished from public view since 1590, the Brownists, or Separatists, as they were called, had persisted in their course, through execration and persecution, as a sect of outlaws beyond the pale of ordinary Puritanism, and with whom moderate Puritans disowned connection or sympathy. One hears of considerable numbers of them in the shires of Norfolk and Essex and throughout Wales; and there was a central association of them in London, holding conventicles in the fields, or shifting from meeting-house to meeting-house in the suburbs, so as to elude Whitgift’s ecclesiastical police. At length, in 1592, the police broke in upon one of the meetings of the London Brownists at Islington; fifty-six of these were thrown into divers jails; and, some of the Separatist leaders having been otherwise arrested, there ensued a vengeance far more ruthless than the government dared against Puritans in general.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

108976 192462Whoa! This weblog looks just like my old one! It is on a completely different topic but it has pretty a lot the same layout and design. Outstanding choice of colors! 112808

354402 910132Normally I try and get my mix of Vitamin E from pills. Although Id actually like to by means of a great meal strategy it can be rather hard to at times. 322952