Today’s installment concludes Romans Establish Republic

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eight thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Romans Establish Republic.

Time: 510 BC

Place: Rome

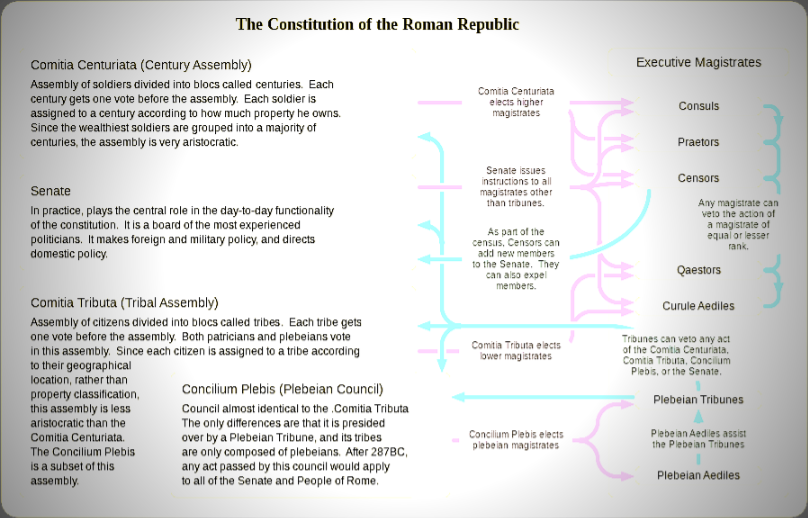

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Meantime news came to the city that the Roman territory was invaded by the Volscian foe. The consuls proclaimed a levy; but the stout yeomen, one and all, refused to give in their names and take the military oath. Servilius now came forward and proclaimed by edict that no citizen should be imprisoned for debt so long as the war lasted, and that at the close of the war he would propose an alteration of the law. The plebeians trusted him, and the enemy was driven back. But when the popular consul returned with his victorious soldiers, he was denied a triumph, and the senate, led by Appius, refused to make any concession in favor of the debtors.

The anger of the plebeians rose higher and higher, when again news came that the enemy was ravaging the lands of Rome. The senate, well knowing that the power of the consuls would avail nothing, since Appius was regarded as a tyrant, and Servilius would not choose again to become an instrument for deceiving the people, appointed a dictator to lead the citizens into the field. But to make the act as popular as might be, they named M. Valerius, a descendant of the great Poplicola. The same scene was repeated over again. Valerius protected the plebeians against their creditors while they were at war, and promised them relief when war was over. But when the danger was gone by, Appius again prevailed; the senate refused to listen to Valerius, and the dictator laid down his office, calling gods and men to witness that he was not responsible for his breach of faith.

The plebeians whom Valerius had led forth were still under arms, still bound by their military oath, and Appius, with the violent patricians, refused to disband them. The army, therefore, having lost Valerius, their proper general chose two of themselves, L. Junius Brutus and L. Sicinius Bellutus by name, and under their command they marched northward and occupied the hill which commands the junction of the Tiber and the Anio. Here, at a distance of about two miles from Rome, they determined to settle and form a new city, leaving Rome to the patricians and their clients. But the latter were not willing to lose the best of their soldiery, the cultivators of the greater part of the Roman territory, and they sent repeated embassies to persuade the seceders to return. They, however, turned a deaf ear to all promises, for they had too often been deceived. Appius now urged the senate and patricians to leave the plebeians to themselves. The nobles and their clients, he said, could well maintain themselves in the city without such base aid.

But wiser sentiments prevailed. T. Lartius, and M. Valerius, both of whom had been dictators, with Menenius Agrippa, an old patrician of popular character, were empowered to treat with the people. Still their leaders were unwilling to listen, till old Menenius addressed them in the famous fable of the “Belly and the Members”:

“In times of old,” said he, “when every member of the body could think for itself, and each had a separate will of its own, they all, with one consent, resolved to revolt against the belly. They knew no reason, they said, why they should toil from morning till night in its service, while the belly lay at its ease in the midst of all, and indolently grew fat upon their labors. Accordingly they agreed to support it no more. The feet vowed they would carry it no longer; the hands that they would do no more work; the teeth that they would not chew a morsel of meat, even were it placed between them. Thus resolved, the members for a time showed their spirit and kept their resolution; but soon they found that instead of mortifying the belly they only undid themselves: they languished for a while, and perceived too late that it was owing to the belly that they had strength to work and courage to mutiny.”

The moral of this fable was plain. The people readily applied it to the patricians and themselves, and their leaders proposed terms of agreement to the patrician messengers. They required that the debtors who could not pay should have their debts cancelled, and that those who had been given up into slavery should be restored to freedom. This for the past. And as a security for the future, they demanded that two of themselves should be appointed for the sole purpose of protecting the plebeians against the patrician magistrates, if they acted cruelly or unjustly toward the debtors. The two officers thus to be appointed were called “Tribunes of the Plebs.” Their persons were to be sacred and inviolable during their year of office, whence their office is called sacrosancta Potestas. They were never to leave the city during that time, and their houses were to be open day and night, that all who needed their aid might demand it without delay.

This concession, apparently great, was much modified by the fact that the patricians insisted on the election of the tribunes being made at the Comitia of the Centuries, in which they themselves and their wealthy clients could usually command a majority. In later times, the number of the tribunes was increased to five, and afterward to ten. They were elected at the Comitia of the tribes. They had the privilege of attending all sittings of the senate, though they were not considered members of that famous body. Above all, they acquired the great and perilous power of the veto, by which any one of their number might stop any law, or annul any decree of the senate without cause or reason assigned. This right of veto was called the “Right of Intercession.”

On the spot where this treaty was made, an altar was built to Jupiter, the causer and banisher of fear, for the plebeians had gone thither in fear and returned from it in safety. The place was called Mons Sacer, or the Sacred Hill, forever after, and the laws by which the sanctity of the tribunitian office was secured were called the Leges Sacratæ.

The tribunes were not properly magistrates or officers, for they had no express functions or official duties to discharge. They were simply representatives and protectors of the plebs. At the same time, however, with the institution of these protective officers, the plebeians were allowed the right of having two ædiles chosen from their own body, whose business it was to preserve order and decency in the streets, to provide for the repair of all buildings and roads there, with other functions partly belonging to police officers, and partly to commissioners of public works.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Romans Establish Republic by Henry George Liddell from his book A History of Rome published in 1855. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Your financial support will enable us to take this treasury of history to the next level.

More information on Romans Establish Republic here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.