There can be no doubt that the wars that followed the expulsion of the Tarquins, with the loss of territory that accompanied them, must have reduced all orders of men at Rome to great distress.

Continuing Romans Establish Republic,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Romans Establish Republic.

Time: 510 BC

Place: Rome

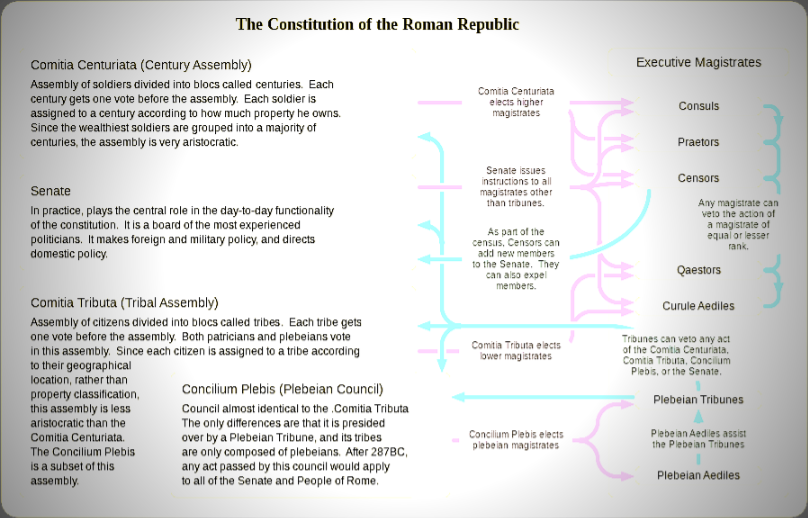

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

We shall now record, not only the slow steps by which the Romans recovered dominion over their neighbors, but also the long-continued struggle by which the plebeians raised themselves to a level with the patricians, who had again become the dominant caste at Rome. Mixed up with legendary tales as the history still is, enough is nevertheless preserved to excite the admiration of all who love to look upon a brave people pursuing a worthy object with patient but earnest resolution, never flinching, yet seldom injuring their good cause by reckless violence. To an Englishman this history ought to be especially dear, for more than any other in the annals of the world does it resemble the long-enduring constancy and sturdy determination, the temperate will and noble self-control, with which the Commons of his own country secured their rights. It was by a struggle of this nature, pursued through a century and a half, that the character of the Roman people was molded into that form of strength and energy, which threw back Hannibal to the coasts of Africa, and in half a century more made them masters of the Mediterranean shore.

There can be no doubt that the wars that followed the expulsion of the Tarquins, with the loss of territory that accompanied them, must have reduced all orders of men at Rome to great distress. But those who most suffered were the plebeians. The plebeians at that time consisted entirely of landholders, great and small, and husbandmen, for in those times the practice of trades and mechanical arts was considered unworthy of a freeborn man. Some of the plebeian families were as wealthy as any among the patricians; but the mass of them were petty yeoman, who lived on the produce of their small farm, and were solely dependent for a living on their own limbs, their own thrift and industry. Most of them lived in the villages and small towns, which in those times were thickly sprinkled over the slopes of the Campagna.

The patricians, on the other hand, resided chiefly within the city. If slaves were few as yet, they had the labor of their clients available to till their farms; and through their clients also they were enabled to derive a profit from the practice of trading and crafts, which personally neither they nor the plebeians would stoop to pursue. Besides these sources of profit, they had at this time the exclusive use of the public land, a subject on which we shall have to speak more at length hereafter. At present, it will be sufficient to say, that the public land now spoken of had been the crown land or regal domain, which on the expulsion of the kings had been forfeited to the state. The patricians being in possession of all actual power, engrossed possession of it, and seem to have paid a very small quit-rent to the treasury for this great advantage.

Besides this, the necessity of service in the army, or militia–as it might more justly be called–acted very differently on the rich landholder and the small yeoman. The latter, being called out with sword and spear for the summer’s campaign, as his turn came round, was obliged to leave his farm uncared for, and his crop could only be reaped by the kind aid of neighbors; whereas the rich proprietor, by his clients or his hired laborers, could render the required military service without robbing his land of his own labor. Moreover, the territory of Rome was so narrow, and the enemy’s borders so close at hand, that any night the stout yeoman might find himself reduced to beggary, by seeing his crops destroyed, his cattle driven away, and his homestead burnt in a sudden foray. The patricians and rich plebeians were, it is true, exposed to the same contingencies. But wealth will always provide some defence; and it is reasonable to think that the larger proprietors provided places of refuge, into which they could drive their cattle and secure much of their property, such as the peel-towers common in our own border counties. Thus the patricians and their clients might escape the storm which destroyed the isolated yeoman.

To this must be added that the public land seems to have been mostly in pasturage, and therefore the property of the patricians must have chiefly consisted in cattle, which was more easily saved from depredation than the crops of the plebeian. Lastly, the profit derived from the trades and business of their clients, being secured by the walls of the city, gave to the patricians the command of all the capital that could exist in a state of society so simple and crude, and afforded at once a means of repairing their own losses, and also of obtaining a dominion over the poor yeoman.

For some time after the expulsion of the Tarquins it was necessary for the patricians to treat the plebeians with liberality. The institutions of “the Commons’ King,” King Servius, suspended by Tarquin, were, partially at least, restored: it is said even that one of the first consuls was a plebeian, and that he chose several of the leading plebeians into the senate. But after the death of Porsenna, and when the fear of the Tarquins ceased, all these flattering signs disappeared. The consuls seem still to have been elected by the Centuriate Assembly, but the Curiate Assembly retained in their own hands the right of conferring the Imperium, which amounted to a positive veto on the election by the larger body. All the names of the early consuls, except in the first year of the Republic, are patrician. But if by chance a consul displayed popular tendencies, it was in the power of the senate and patricians to suspend his power by the appointment of a dictator. Thus, practically, the patrician burgesses again became the Populus, or body politic of Rome.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.