Thus the free plebeian population might have been reduced to a state of mere dependency, and the history of Rome might have presented a repetition of monotonous severity.

Continuing Romans Establish Republic,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Romans Establish Republic.

Time: 510 BC

Place: Rome

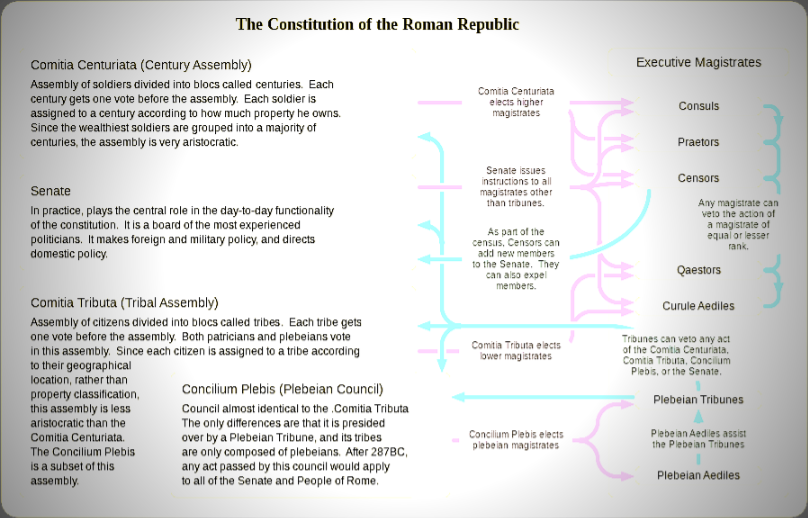

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

It must not here be forgotten that this dominant body was an exclusive caste; that is, it consisted of a limited number of noble families, who allowed none of their members to marry with persons born out of the pale of their own order. The child of a patrician and a plebeian, or of a patrician and a client, was not considered as born in lawful wedlock; and however proud the blood which it derived from one parent, the child sank to the condition of the parent of lower rank. This was expressed in Roman language by saying, that there was no “Right of Connubium” between patricians and any inferior classes of men. Nothing can be more impolitic than such restrictions; nothing more hurtful even to those who count it their privilege. In all exclusive or oligarchical,pales, families become extinct, and the breed decays both in bodily strength and mental vigor. Happily for Rome, the patricians were unable long to maintain themselves as a separate caste.

Yet the plebeians might long have submitted to this state of social and political inferiority, had not their personal distress and the severe laws of Rome driven them to seek relief by claiming to be recognized as members of the body politic.

The severe laws of which we speak were those of debtor and creditor. If a Roman borrowed money, he was expected to enter into a contract with his creditor to pay the debt by a certain day; and if on that day he was unable to discharge his obligation, he was summoned before the patrician judge, who was authorized by the law to assign the defaulter as a bonds man to his creditor–that is, the debtor was obliged to pay by his own labor the debt which he was unable to pay in money. Or if a man incurred a debt without such formal contract, the rule was still more imperious, for in that case the law itself fixed the day of payment; and if after a lapse of thirty days from that date the debt was not discharged, the creditor was empowered to arrest the person of his debtor, to load him with chains, and feed him on bread and water for another thirty days; and then, if the money still remained unpaid, he might put him to death, or sell him as a slave to the highest bidder; or, if there were several creditors, they might hew his body in pieces and divide it. And in this last case the law provided with scrupulous providence against the evasion by which the Merchant of Venice escaped the cruelty of the Jew; for the Roman law said that “whether a man cut more or less [than his due], he should incur no penalty.” These atrocious provisions, however, defeated their own object, for there was no more unprofitable way in which the body of a debtor could be disposed of.

Such being the law of debtor and creditor, it remains to say that the creditors were chiefly of the patrician caste, and the debtors almost exclusively of the poorer sort among the plebeians. The patricians were the creditors, because from their occupancy of the public land, and from their engrossing the profits to be derived from trade and crafts, they alone had spare capital to lend. The plebeian yeomen were the debtors, because their independent position made them, at that time, helpless. Vassals, clients, serfs, or by whatever name dependents are called, do not suffer from the ravages of a predatory war like free landholders, because the loss falls on their lords or patrons. But when the independent yeoman’s crops are destroyed, his cattle “lifted,” and his homestead in ashes, he must himself repair the loss. This was, as we have said, the condition of many Roman plebeians. To rebuild their houses and restock their farms they borrowed; the patricians were their creditors; and the law, instead of protecting the small holders, like the law of the Hebrews, delivered them over into serfdom or slavery.

Thus the free plebeian population might have been reduced to a state of mere dependency, and the history of Rome might have presented a repetition of monotonous severity, like that of Sparta or of Venice.[1] But it was ordained otherwise. The distress and oppression of the plebeians led them to demand and to obtain political protectors, by whose means they were slowly but surely raised to equality of rights and privileges with their rulers and oppressors. These protectors were the famous Tribunes of the Plebs. We will now repeat the no less famous legends by which their first creation was accounted for.

[Footnote 1: A well-known German historian calls the Spartans by the name of “stunted Romans.” There is much resemblance to be traced.]

It was, by the common reckoning, fifteen years after the expulsion of the Tarquins (B.C. 494), that the plebeians were roused to take the first step in the assertion of their rights. After the battle of Lake Regillus, the plebeians had reason to expect some relaxation of the law of debt, in consideration of the great services they had rendered in the war. But none was granted. The patrician creditors began to avail themselves of the severity of the law against their plebeian debtors. The discontent that followed was great, and the consuls prepared to meet the storm. These were Appius Claudius, the proud Sabine nobleman who had lately become a Roman, and who now led the high patrician party with all the unbending energy of a chieftain whose will had never been disputed by his obedient clansmen; and P. Servilius, who represented the milder and more liberal party of the Fathers.

It chanced that an aged man rushed into the Forum on a market-day, loaded with chains, clothed with a few scanty rags, his hair and beard long and squalid; his whole appearance ghastly, as of one oppressed by long want of food and air. He was recognized as a brave soldier, the old comrade of many who thronged the Forum. He told his story, how that in the late wars the enemy had burned his house and plundered his little farm; that to replace his losses he had borrowed money of a patrician, that his cruel creditor (in default of payment) had thrown him into prison,[2] and tormented him with chains and scourges. At this sad tale, the passions of the people rose high.

[Footnote 2: Such prisons were called ergastula, and afterward became the places for keeping slaves in.]

Appius was obliged to conceal himself, while Servilius undertook to plead the cause of the plebeians with the senate.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.