Today is Thanksgiving Day.

The old-time New England Thanksgiving has been described many times, but never better then by the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in her less successful but more artistic novel, Oldtown Folks, from which the following passage has been adapted.

by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Great as the preparations were for the dinner, everything was so contrived that not a soul in the house should be kept from the morning service of Thanksgiving in the church, and from listening to the Thanksgiving sermon, in which the minister was expected to express his views freely concerning the politics of the country and the state of things in society generally, in a somewhat more secular vein of thought than was deemed exactly appropriate to the Lord’s day. But it is to be confessed that, when the good man got carried away by the enthusiasm of his subject to extend these exercises beyond a certain length, anxious glances, exchanged between good wives, sometimes indicated a weakness of the flesh, having a tender reference to the turkeys and chickens and chicken pies which might possibly be overdoing in the ovens at home. But your old brick oven was a true Puritan institution, and backed up the devotional habits of good housewives by the capital care which he took of whatever was committed to his capacious bosom. A truly well-bred oven would have been ashamed of himself all his days and blushed redder than his own fires, if a God-fearing house matron, away at the temple of the Lord, should come home and find her pie crust either burned or underdone by his over or under zeal; so the old fellow generally managed to bring things out exactly right.

When sermons and prayers were all over, we children rushed home to see the great feast of the year spread.

What chitterings and chatterings there were all over the house, as all the aunties and uncles and cousins came pouring in, taking off their things, looking at one another’s bonnets and dresses, and mingling their comments on the morning sermon with various opinions on the new millinery outfits, and with bits of home news and kindly neighbourhood gossip.

Uncle Bill, whom the Cambridge college authorities released, as they did all the other youngsters of the land, for Thanksgiving Day, made a breezy stir among them all, especially with the young cousins of the feminine gender.

The best room on this occasion was thrown wide open, and its habitual coldness had been warmed by the burning down of a great stack of hickory logs, which had been heaped up unsparingly since morning. It takes some hours to get a room warm where a family never sits, and which therefore has not in its walls one particle of the genial vitality which comes from the indwelling of human beings. But on Thanksgiving Day, at least, every year this marvel was effected in our best room.

Although all servile labor and vain recreation on this day were by law forbidden, according to the terms of the proclamation, it was not held to be a violation of the precept that all the nice old aunties should bring their knitting work and sit gently trotting their needles around the fire; nor that Uncle Bill should start a full-fledged romp among the girls and children, while the dinner was being set on the long table in the neighboring kitchen. Certain of the good elderly female relatives, of serious and discreet demeanor, assisted at this operation.

But who shall do justice to the dinner, and describe the turkey, and chickens, and chicken pies, with all that endless variety of vegetables which the American soil and climate have contributed to the table, and which, without regard to the French doctrine of courses, were all piled together in jovial abundance upon the smoking board? There was much carving and laughing and talking and eating, and all showed that cheerful ability to despatch the provisions which was the ruling spirit of the hour. After the meat came the plum puddings, and then the endless array of pies, till human nature was actually bewildered and overpowered by the tempting variety; and even we children turned from the profusion offered to us, and wondered what was the matter that we could eat no more.

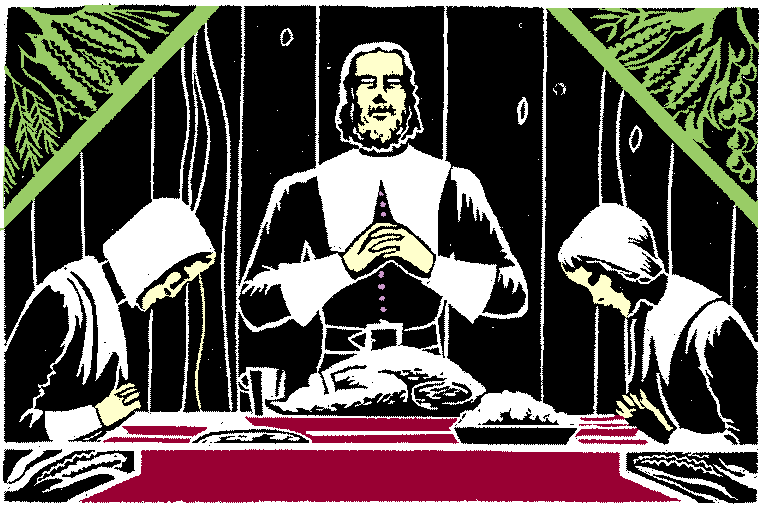

When all was over, my grandfather rose at the head of the table, and a fine venerable picture he made as he stood there, his silver hair flowing in curls down each side of his clear, calm face, while, in conformity to the old Puritan custom, he called their attention to a recital of the mercies of God in His dealings with their family.

It was a sort of family history, going over and touching upon the various events which had happened. He spoke of my father’s death, and gave a tribute to his memory; and closed all with the application of a time-honoured text, expressing the hope that as years passed by we might “so number our days as to apply our hearts unto wisdom”; and then he gave out that psalm which in those days might be called the national hymn of the Puritans.

Let children hear the mighty deeds

Which God performed of old,

Which in our younger years we saw,

And which our fathers told.

He bids us make his glories known,

His works of power and grace.

And we’ll convey his wonders down

Through every rising race.

Our lips shall tell them to our sons,

And they again to theirs;

That generations yet unborn

May teach them to their heirs.

Thus shall they learn in God alone

Their hope securely stands;

That they may ne’er forget his works,

But practise his commands.”

This we all united in singing to the venerable tune of St. Martin’s, an air which, the reader will perceive, by its multiplicity of quavers and inflections gave the greatest possible scope to the cracked and trembling voices of the ancients, who united in it with even more zeal than the younger part of the community.

Uncle Fliakim Sheril, furbished up in a new crisp black suit, and with his spindleshanks trimly incased in the smoothest of black silk stockings, looking for all the world just like an alert and spirited black cricket, outdid himself on this occasion in singing counter, in that high, weird voice that he must have learned from the wintry winds that usually piped around the corners of the old house. But any one who looked at him, as he sat with his eyes closed, beating time with head and hand, and, in short, with every limb of his body, must have perceived the exquisite satisfaction which he derived from this mode of expressing himself. I much regret to be obliged to state that my graceless Uncle Bill, taking advantage of the fact that the eyes of all his elders were devotionally closed, stationing himself a little in the rear of my Uncle Fliakim, performed an exact imitation of his counter with such a killing facility that all the younger part of the audience were nearly dead with suppressed laughter. Aunt Lois, who never shut her eyes a moment on any occasion, discerned this from a distant part of the room, and in vain endeavoured to stop it by vigorously shaking her head at the offender. She might as well have shaken it at a bobolink tilting on a clover top. In fact, Uncle Bill was Aunt Lois’s weak point, and the corners of her own mouth were observed to twitch in such a suspicious manner that the whole moral force of her admonition was destroyed.

And now, the dinner being cleared away, we youngsters, already excited to a tumult of laughter, tumbled into the best room, under the supervision of Uncle Bill, to relieve ourselves with a game of “blindman’s bluff,” while the elderly women washed up the dishes and got the house in order, and the men folks went out to the barn to look at the cattle, and walked over the farm and talked of the crops.

In the evening the house was all open and lighted with the best of tallow candles, which Aunt Lois herself had made with especial care for this illumination. It was understood that we were to have a dance, and black Cæsar, full of turkey and pumpkin pie, and giggling in the very jollity of his heart, had that afternoon rosined his bow, and tuned his fiddle, and practiced jigs and Virginia reels, in a way that made us children think him a perfect Orpheus….

Further information on: Thanksgiving Day.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.