This series has three easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Republican Party Forms.

Introduction

Caught between the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Whig Party’s equivocating, dissenters found themselves forced to start a new party, the Republican Party. The Democratic Party’s policy was to allow slavery to continue to spread, subject to local approval. This had become too large an issue; equivocating on it was no longer acceptable to many in the north. This is the story of the Republicans’ First National Convention.

This selection is from Abraham Lincoln, A History by John Hay and John G. Nicolay published in 1890. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages

The authors were Lincoln’s Presidential Staff. Amazing to think that a President’s entire staff would consist of just two men. John Hay ended his career as Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of State.

Time: 1856

Place: Pittsburg

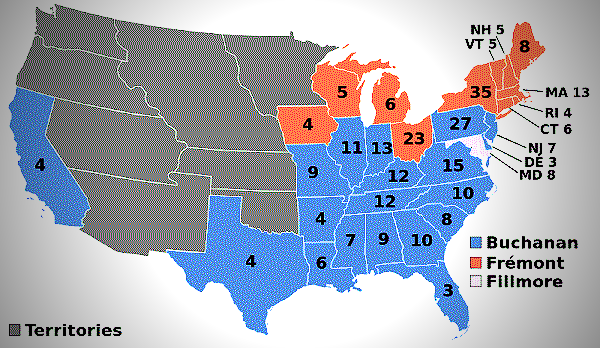

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Bloomington Convention came together according to call on the 29th of May. By this time the active and observant politicians of the State [Illinois – jl] had become convinced that the anti-Nebraska struggle was not a mere temporary and insignificant “abolition” excitement, but a deep and abiding political issue, involving in the fate of slavery the fate of the nation. Minor and past differences were therefore generously postponed or waived in favor of a hearty coalition on the single dominant question. A most notable gathering of the clans was the result. About one-fourth of the counties sent regularly chosen delegates; the rest were volunteers. In spirit and enthusiasm it was rather a mass-meeting than a convention; but every man present was in some sort a leader in his own locality. The assemblage was much more representative than similar bodies gathered by the ordinary caucus machinery. It was an earnest and determined council of five or six hundred cool, sagacious, independent thinkers, called together by a great public exigency, led and directed by the first minds of the State. Not only did it show a brilliant array of eminent names, but a remarkable contrast of former antagonisms: Whigs, Democrats, Free-Soilers, Know-Nothings, Abolitionists; Norman B. Judd, Richard Yates, Ebenezer Peck, Leonard Swett, Lyman Trumbull, David Davis, Owen Lovejoy, Orville H. Browning, Ichabod Godding, Archibald Williams, and many more. Chief among these, as adviser and actor, was Abraham Lincoln.

Rarely has a deliberative body met under circumstances more exciting than did this one. The Congressional debates at Washington and the civil war in Kansas were each at a culmination of passion and incident. Within ten days Charles Sumner had been struck down in the Senate Chamber, and the town of Lawrence sacked by the guerrilla posse of Atchison and Sheriff Jones. Ex-Governor Reeder, of that suffering Territory, addressed the citizens of Bloomington and the earliest-arriving delegates on the evening of the 28th, bringing into the convention the very atmosphere of the Kansas conflict.

The convention met and conducted its work with earnestness and dignity. Bissell, already designated by unmistakable popular indications, was nominated for governor by acclamation. The candidate for lieutenant-governor was named in like manner. So little did the convention think or care about the mere distribution of political honors on the one hand, and so much, on the other, did it regard and provide for the success of the cause, that it did not even ballot for the remaining candidates on the State ticket, but deputed to a committee the task of selecting and arranging them, and adopted its report as a whole and by acclamation. The more difficult task of drafting a platform was performed by another committee, with such prudence that it too received a unanimous acceptance. It boldly adopted the Republican name, formulated the Republican creed, and the convention further appointed delegates to the coming Republican National Convention.

There were stirring speeches by eloquent leaders, eagerly listened to and vociferously applauded; but scarcely a man moved from his seat in the crowded hall until Mr. Lincoln had been heard. Every one felt the fitness of his making the closing argument and exhortation, and right nobly did he honor their demand. A silence full of emotion filled the assembly as for a moment before beginning his tall form stood in commanding attitude on the rostrum, the impressiveness of his theme and the significance of the occasion reflected in his thoughtful and earnest features. The spell of the hour was visibly upon him; and holding his audience in rapt attention, he closed in a brilliant peroration with an appeal to the people to join the Republican standard, to

Come as the winds come, when forests are rended; Come as the waves come, when navies are stranded.”

The influence was irresistible; the audience rose and acknowledged the speaker’s power with cheer upon cheer. Unfortunately the speech was never reported; but its effect lives vividly in the memory of all who heard it, and it crowned his right to popular leadership in his own State, which thereafter was never disputed.

The organization of the Republican party for the nation at large proceeded very much in the same manner as that in the State of Illinois. Pursuant to separate preliminary correspondence and calls from State committees, a general meeting of prominent Republicans and anti-Nebraska politicians from all parts of the North, and even from a few border slave-States, came together at Pittsburgh on Washington’s birthday, February 22. Ohio, New York, and Pennsylvania sent the largest contingents; but around this great central nucleus were gathered small but earnest delegations aggregating between three and four hundred zealous leaders, representing twenty-eight States and Territories. It was merely an informal mass convention; but many of the delegates were men of national character, each of whose names was itself a sufficient credential. Above all, the members were cautious, moderate, conciliatory, and unambitious to act beyond the requirements of the hour. They contented themselves with the usual parliamentary routine; appointed a committee on national organization; issued a call for a delegate convention; and adopted and put forth a stirring address to the country. Their resolutions were brief and formulated but four demands: the repeal of all laws which allow the introduction of slavery into Territories once consecrated to freedom; resistance by constitutional means to slavery in any United States Territory; the immediate admission of Kansas as a free-State, and the overthrow of the present national Administration.

In response to the official call embodied in the Pittsburgh address, the first National Convention of the Republican party met at Philadelphia on the 17th of June, 1856. The character and dignity of the Pittsburgh proceedings assured the new party of immediate prestige and acceptance; with so favorable a sponsorship it sprang full-armed into the political conflict.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.